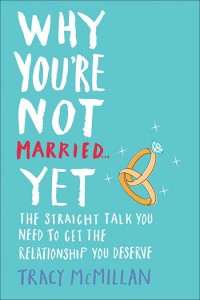

A new book hit shelves this month blaming women for not finding a husband on their own character flaws. Tracy McMillan’s Why You’re Not Married Yet, suggests that the reason single ladies don’t have a ring on their finger is because they are either a bitch, shallow, a slut, crazy, selfish, a mess, hate themselves, a liar, acting like ‘a dude’ or think they are goddesses. Each chapter covers each reason.

The labels are of course tongue-in-cheek and some of her observations of female character flaws are laugh-out-loud funny. But a lot is said in jest and her underlying message is that single is a dreadful affliction. Not only does this send the image of independent modern woman right back to Bridgette Jones lows, it is also way off the mark.

The labels are of course tongue-in-cheek and some of her observations of female character flaws are laugh-out-loud funny. But a lot is said in jest and her underlying message is that single is a dreadful affliction. Not only does this send the image of independent modern woman right back to Bridgette Jones lows, it is also way off the mark.

As I wrote in The Telegraph this week, I’ve spent most of my life single. I’ve had a few long-term relationships and way more than my fair share of short-term ones but I’ve always felt a greater zest for life when navigating the world alone. My energy, my sense of adventure, my ambition, my friends, my fitness, my career, my joi de vivre all seem to thrive when single. I have loved men ferociously but a little part of me wilts when I belong to someone else.

McMillan’s advise may have been appropriate for 1950s Britain, referred to by historians and as the golden age of marriage because of the universal male-breadwinning, female-happy-homemaking, family-focused ideal.

It was hard for a woman to imagine any other path through life back then. Marriage historian Stephanie Coontz, in her hit book Marriage, a History, mentions a survey from 1957 showing 80% of people believed that anyone who preferred to remain single was ‘sick, neurotic or immoral.’

In the 1950s married couples represented 85% of all households in the UK. Last year this figure was 67%. The number of ‘married’ and ‘never married’ women is predicted to be equal by 2031.

This indicates how out of date the premise of this book is. To modern women, marriage is no longer Nirvana. As a journalist specialising in modern models of relationships, I’ve met single women choosing to have babies through sperm donors, committed couples who live apart, single men and women functioning as co-parents, asexuals, bisexuals, polyamorous ‘triads’ and all manner of different arrangements. None of them seemed like sociopaths to me.

McMillan wrote the book after a piece on The Huffington post last year with the same title went viral, so there must be plenty of bride wannabes out there.

But I don’t see marriage as an accolade of success. I’m not against relationships. In fact, for the first time in six years I am in one. It’s wonderful. A warm fuzz of shared intimacies, jokes and a constant narrative on someone else’s life. But there are aspects of my single life that I miss too – the freedom not to plan, more time to see my friends and a seven-day staple of quality sleep. I don’t view coupledom any more or less honourable or enjoyable as singledom. Like living in the city or the country.

I’ve nothing against commitment either. I’ve more than sated a thirst for sexual experimentation (and wrote a book  about it). Maybe we’ll be together forever, or maybe we’ll tire of each other but marriage is not a goal. It doesn’t ring out any notes of achievement or sense of completion. On the contrary, I think defining oneself through their legal, permanent association with another is a cheap tactic for self-esteem.

about it). Maybe we’ll be together forever, or maybe we’ll tire of each other but marriage is not a goal. It doesn’t ring out any notes of achievement or sense of completion. On the contrary, I think defining oneself through their legal, permanent association with another is a cheap tactic for self-esteem.

Telling women how to improve themselves to win a spouse only devalues marriage. It makes it a superficial symbol of status – like a designer handbag. A wedding ring to showcase your ability to scoop someone’s heart. I’ve been complimented more in Primark than Prada. In the same way, people can love more fiercely and loyally without a ring and ceremony and four bedroom home with a manicured lawn.

Who is to say that commitment means merging lifestyles anyway? The rise of solo living is on the up. In 1950 only 10% of households in this country contained only one person. Last year 29% of homes were single-occupied.

One of those is me. I adore the man in my life but I’ve made it very clear that we won’t be sharing front doors. I can’t express how much I love living alone. There is no nicer sound at the end of a full day than a handbag thudding to the floor of an empty flat, the clicking on of lamps and the opening of the fridge to see what’s there – and finding everything is!

Unless I had children – and at 35 I haven’t had one of those pangs – I can’t see one benefit to sharing living space. Whoever thought that drawing a daily compromise agreement on everything from choice of wallpaper to what time you set the alarm clock was romantic, needs their head examined.

I know what you’re thinking: I’m going to die alone with cats. I have been charged with this before. But this is a myopic and selfish vision. It is selfish because it presumes that we should use a relationship as an insurance policy: Commit your life as protection against the possibility that you’ll become lonely or dependent in later life. One survey out last month claimed 51% of us are over-insured. And that, I doubt, doesn’t include people staying in mediocre relationships just in case.

It is myopic because by the time I am 85, I doubt loneliness will be as menacing as it may be for today’s octogenarians. The single women McMillan targets are children of the social networking revolution. I have no doubt that if I reach 85, whatever well-worn, wizened state I am in – single, married or co-habiting – there will be many others like me, all using some uber-techy networking apps to put ourselves in touch with each other.

In the same week as McMillan’s book, another one, Single: Arguments For The Uncoupled by Canadian academic Michael Cobb argues that single people are marginalised. Despite studies showing us that marriage doesn’t make us happier, he asks why we still put it on a pedestal. He complains that in books and films negative emotions such as despair anxiety or isolation are always visited through the singleton. No happy ending is complete until the single protégés are fixed.

Whenever I’ve been single my friends have constantly tried to rectify it. They’d get excited if I said a date was enjoyable – as though there were hope for my pitiful state. I hear stories that marriage is ‘the hardest thing you can do’, ‘the toughest test of character’ and ‘living with someone requires compromise.’ Well I concur. And that’s why I’m staying well away.

By HELEN CROYDON, The Huffington Post