“The greatest triumph of Satan is convincing people in the modern age it doesn’t exist.” Anonymous

A forgotten phrase—“Orangeburg Massacre”—came to mind as we were driving into town. When a good ole boy came across the street and started spouting ‘nigger this’ and ‘nigger that,’ I knew we’d driven into hell.

A forgotten phrase—“Orangeburg Massacre”—came to mind as we were driving into town. When a good ole boy came across the street and started spouting ‘nigger this’ and ‘nigger that,’ I knew we’d driven into hell.

It was 1993. My companion had been hired to teach at South Carolina State in Orangeburg, and I was going into the philosophy grad program at the University of South Carolina in Columbia. Our new neighbor saw the California plates and wanted to know if we would fit into proper southern white society.

The third time he used the word nigger, I knew I couldn’t forgive myself if I let it go, new to the neighborhood or not. Standing on the back of the rental truck, I said, “I take people as I find them, one at a time.”

That’s the antithesis of the racist’s attitude of course. He replied, “There are two kinds of Yankees: Yankees and damn Yankees. Yankees come down here to visit; damn Yankees come down here to live.” Even in Mexico, I’d never been called a Yankee, much less a damn Yankee.

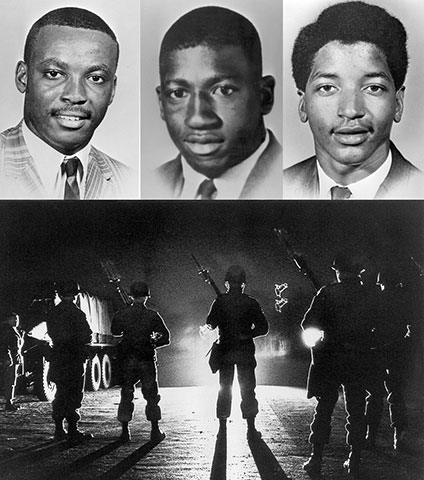

This was our welcome to South Carolina, where the Confederate flag still flew over the Capitol (they’ve since ‘removed’ it to the plaza in front). Wanting to know how deep a shithole we had fallen into, I asked the racist if he knew anything about the Orangeburg Massacre. Three black protesters were gunned down by State Police in Orangeburg demonstrating against racial segregation at a local bowling alley in February 1968.

“I was there!” he pridefully exclaimed. “I stood right next to a State cop that pointed at a big buck, and he said, ‘I’m going to put a bullet right here,’ and tapped his forehead. Then he did.” Three young black men were killed in an incident few people in this country even know happened.

Needless to say, things didn’t work out for us, and we left the Palmetto State a few months later. The college had broken its contract, and there was no way we could stay. It turns out ‘southern hospitality’ is a pail of whitewash.

Before driving north we took a trip to Charleston. After taking a tour of that beautiful city, which includes places were slaves were sold, we were desultorily walking around when we came upon an unmarked 18th century building. We noted the architecture, with its Roman pillars, and turned to cross the street.

My companion, who had evinced ‘sensings’ of other places before (which I had largely dismissed as imaginings), suddenly turned pasty white and began to wobble. “Terrible things have happened here,” she said, as I steadied her, “children being ripped from their parents, and lots of other horrible things.”

Back in Orangeburg, we had been invited to dinner by two black professors, a tenured couple at South Carolina State. When we told them what  happened they asked the precise location, and said gravely, “Most white people don’t know it, but that was a the place where most of the slaves where sold in the Old South. It carries a lot of meaning for us.”

happened they asked the precise location, and said gravely, “Most white people don’t know it, but that was a the place where most of the slaves where sold in the Old South. It carries a lot of meaning for us.”

We left South Carolina, never to return. Until the massacre at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, I had heard that things had improved, that the racism we witnessed had lessened, and that black people no longer felt like second-class citizens, even when they had PhDs and full tenure. But evil runs deep, and is not easily dispelled.

There are so many intertwined issues involved in the planned, vicious slaughter of nine examples of America’s finest citizens: The still suppurating wound of racism; the rampant alienation in the United States today; the national gun fetish; and the soul deadness and undercurrent of evil that finds easy conductivity through so-called zombies.

When a people perish, most people in the land emotionally experience it as the death of humanity, and subconsciously adapt by becoming inwardly dead themselves. That vicious cycle explains a great deal of the enervation and misanthropy so many people feel these days. It’s also the main reason why there was no movement on gun control at the national level even after the slaughter of young children in Newtown, Connecticut.

Evil, which is not supernatural but man-made and self-made, is a collective death wish in human consciousness. Its goal (and yes, evil has intentionality) is to kill the human spirit and make everyone dead like it.

Some victim’s families are already expressing forgiveness during their excruciating articulations of loss of their loved ones, as a testimony to their Christian beliefs. But not even Jesus could forgive evil like this that quickly.

We turn the tables on evil, and begin to dispel it, when we use incidents like this, as well as everyday encounters with the darkness that permeates the land, to look deeply within and learn about ourselves.

We thereby remain alive and spiritually growing, exactly what Mara, Satan, or whatever name you want to give it, hates the most.

Martin LeFevre