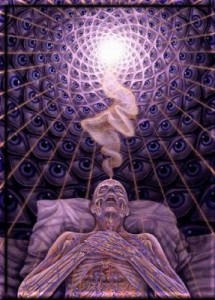

I don’t really like the word ‘mystical.’ It’s imprecise, and full of contradictory meanings, from divine to derisive. But carefully considered, the word may point to a limitless uncharted territory within.

Our relationship, or lack of it, to nature is the first determinant of our relationship to other people and the world. It is the fountainhead (Ayn Rand’s philosophy be damned) of our worldview, and the gateway to, or blockage of higher consciousness for us, and our children’s children.

Our relationship, or lack of it, to nature is the first determinant of our relationship to other people and the world. It is the fountainhead (Ayn Rand’s philosophy be damned) of our worldview, and the gateway to, or blockage of higher consciousness for us, and our children’s children.

Indeed, as other religious philosophers have pointed out, if we have no relationship to nature, we have no relationship to human beings.

So to my mind mystical experiencing first refers to the irreducible mystery of life, embodied by a fluorescing hummingbird hovering over a flower, or the painfully sweet peel of a baby girl’s repetitive vocalizations. Science can explain these things, and the knowledge gained can add to our appreciation, but if knowledge is put first, it subtracts from the immeasurable mystery of essence.

More and more people in our post-industrial, post-modern, post-religion world suffer from ennui, which is synonymous with world-weariness and an enervating boredom with everything. To the extent that information overload, over-familiarity, and overwhelming conformity in thinking and feeling dominate the culture (that is, the sea in which we all swim), ennui is the inevitable emotional state.

What animates our lives is not rational explanation but emotional impact and responsiveness. And religious feeling, however one defines, derides, or deconstructs it, is still the most important higher-level human feeling. Without attending to the religious dimension within ourselves, people and society veer from the intellect to the base emotions, from the barren labyrinths of analytical philosophy to the meaningless pits of pleasure pursued as the highest thing.

On one level, mystical experiencing entails putting the heart before the head. But it goes far beyond such easy bromides, since the capacity to feel sublimities beyond the mind requires continual checking by the mind to avoid delusion.

Intellectuals have developed a specious, knee-jerk reaction to philosophies of nature and human nature that don’t fit within their frameworks of rationality. They dismiss as anthropocentrism any suggestion that the human brain could have any greater meaning in and relationship to the universe beyond what thought and knowledge can conceive.

Such a view is not only arrogant; it’s ironic, precisely because it is arrogant to believe that man is the measure of all things. I’m not referring to Protagoras’ idea that the individual human being, rather than the gods or an unchanging moral law, is the ultimate source of value. I’m referring to the attitude, indeed belief that nothing exists beyond what our brains using thought devise.

Given that anthropocentrism literally means putting man at the center, isn’t the belief that insight and meaning originate solely from within our heads the real anthropocentrism?

In any case, the use of the label amounts to a clever dismissal, a reduction of wordlessly subtle states of mystical experiencing (for lack of a better term) to the antediluvian realm of humankind’s pre-scientific superstition, supernaturalism, and supremacy.

Thus the rationalist’s worldview is merely the other side of the same coin of the believer’s mind. It is no more attuned to the mysteries of life and human existence than the believer’s creed of a separate ‘Supreme Being’ that willed the universe into existence, and occasionally intervenes in human affairs through natural disasters.

Thus the rationalist’s worldview is merely the other side of the same coin of the believer’s mind. It is no more attuned to the mysteries of life and human existence than the believer’s creed of a separate ‘Supreme Being’ that willed the universe into existence, and occasionally intervenes in human affairs through natural disasters.

The human brain is the most complex organ to have evolved on this planet, affording us consciousness as all of us have known it, and mystical experiencing as few have developed it. Without being anthropocentric, I submit that brains such as ours, wherever they evolve, have tremendous significance in the universe, beyond any scientific and technological achievement.

The human brain evolved inextricably in nature, and life on this planet is certainly not some fluke of nature in the universe. That means the dualistic question of whether mystical experiencing originates from inside or outside the human brain is a pointless separation, and becomes nonsensical.

To my mind the question is: Does the deeply silent human mind (as thought) open the human brain–which actually enfolds all brains that have ever evolved on earth–to awareness of an unnamable essence?

Sitting under a sycamore on the edge of town, I listen to the recent return of water in what had been a stream of stones a week ago.

As the sun sinks behind the trees and nears the horizon, I can feel, in a meditative state (which is really simply the movement of negation in attention), changes by the minute. Not only does it grow palpably cooler on what had been a shirtsleeve afternoon at the peak of autumn in northern California, but also smells are suddenly stronger, and sounds sharper.

On a day that until then had felt more like summer, there is the distinct feeling of the earth withdrawing, hinting of winter’s cold and rain in a few more weeks. A reverence, beyond the word and the world, suddenly fills one, and an intimation of something one does not know and cannot know, but can only sense and feel, beyond emotion.

Six Canadian geese fly over in formation, the last rays of the sun glinting off their underwings. It’s a fitting finale to the first sitting of the season on Little Chico Creek.

Martin LeFevre