Carl Jung famously said, “The gods have become diseases.” By this he meant (I think) that the underlying myths, or ‘archetypes’ have come loose from their moorings, and degenerated into pathology. The cure that archetypal psychologists recommend is to “find a myth in the mess.”

Some Jungian psychologists, such as Glen Slater, have spoken eloquently about “the interdependence of psychology and religion,” pointing out that “to be psychological with any depth requires a religious sensibility.”

Slater means religious in a very different sense, since now, as he says, “Golf is a religion, the NRA is a religion, but Catholicism is mostly a squabble between conservative moralists and liberal champions of social justice.”

However without fervor (religious or otherwise), Slater rhetorically asks, “Do we have to face the question of religion again on a whole new level?”

Is there no passion because the cure Jungians prescribe is to “find a myth in the mess” when myths no longer hold any  meaning? How can we “move our psychic compulsions into older vessels,” when the vessels lie cracked and broken on the floor?

meaning? How can we “move our psychic compulsions into older vessels,” when the vessels lie cracked and broken on the floor?

We don’t even know what myths, in the deeper sense of the word, are anymore. (Slater favorably quotes a student defining a myth as “a bizarre story that can change the way a person acts.”)

An archetype is even harder to define. The dictionary defines archetype as “the original pattern or model; prototype.”

In terms of Jung, “archetypal ideas and patterns reside within the collective unconscious, which is a blueprint inherent in every individual, as opposed to the personal unconscious, which contains a single individual’s repressed ideas, desires and memories as described by Freud.”

Jung, and a latter-day Jungian, James Hillman, who initiated “archetypal psychology” in the early 1970’s, felt that the “rise of depth psychology occurs against a background of religious decline, more pointedly the decline of symbolic and ritual life.”

Myths, rituals and traditions have lost not only their meaning, but also their recoverability as foundational aspects of the human psyche.

And there’s the rub for potential Homo sapiens (‘wise humans’) in our age. For good but mostly for ill at this point, human consciousness is being digitized.

What we face, as individuals and a species, is a crisis of symbolic thought itself, the foundation, in one mythological and linguistic form or another, upon which human consciousness has been built for tens of thousands of years.

That means the human crisis goes far deeper than even depth psychologists realize. It’s not a crisis of myth, or narrative, or archetype, but of human consciousness itself.

It also means an adequate response to the crisis of consciousness cannot occur within any conceptual framework, however all-encompassing it may appear to be.

Hillman maintained, “Civilization requires a hero myth, and in fact is built on that myth.” He felt that “the hero who serves the gods founds civilization.” As much as that resonates with what civilization used to be, it is as alien to our post-modern ears as ancient Greek.

Archetypal psychologists carry this idea to its logical and desiccated end, saying not just that present-day Odysseans will mend present-day Ithacas upon their return from the underworld, but proclaim “myth as hero.”

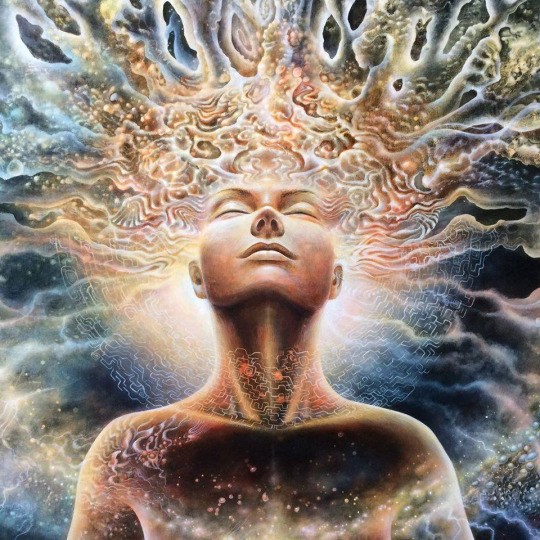

The trouble with speaking of gods in solely mythical and metaphorical terms is that it fails to perceive the impetus of the archetype itself. In the digital age, human beings can and must begin growing into gods, and I don’t mean by merging with AGI, which will be the end of humanity.

The gods, to whatever degree they actually exist in corporeal or incorporeal form, were once human beings. They grew into gods not only by transcending ego, but by dying to images, myths and symbols, and merging with the consciousness of the cosmos itself.

If we observe the movement of thought and emotion at a deeper level, we see that there is no such thing as “individual consciousness,” and that the movement of thought itself ends, falls silent, in complete, undirected attention.

Even so, at some point in the near future, all this ‘individual’ work, which often lacks the urgency our self-made situation on this planet requires, will cease to matter for our age.

We need to act as though this is the last juncture at which humankind can change course, because we can’t know when it’s too late until it is. (Though many, in numbing comfort, believe it already is.)

We’re witnessing, at man’s hands, the collapse of the polar ice sheets and of the biodiversity of animals and plants on the earth. Humans are the species that stepped out of the embrace of ecological niche in nature and are fragmenting the earth all to hell.

That pressing reality presents the deepest philosophical, spiritual and psychological questions. How could the earth’s only sentient, potentially sapient species come to this pass?

Whatever insights one may have in response to that question, living generations are faced with the tremendous responsibility of radically changing.

Martin LeFevre