Costa Rica News – In a part of the world known for guerrillas, drug runners and fleeing emigrees, Costa Rica has long been the exception. It was an oasis of tranquility and stability — the Switzerland of Central America, some took to calling it. American retirees flocked to its beach towns, tourists to its rain forests, investors to its bonds, and the economy churned out steady, if not always spectacular, growth rates.

But there was a weakness to that success story: a budget deficit that’s been constantly growing, slowly eroding an economy that’s become largely dependent on U.S. dollars.

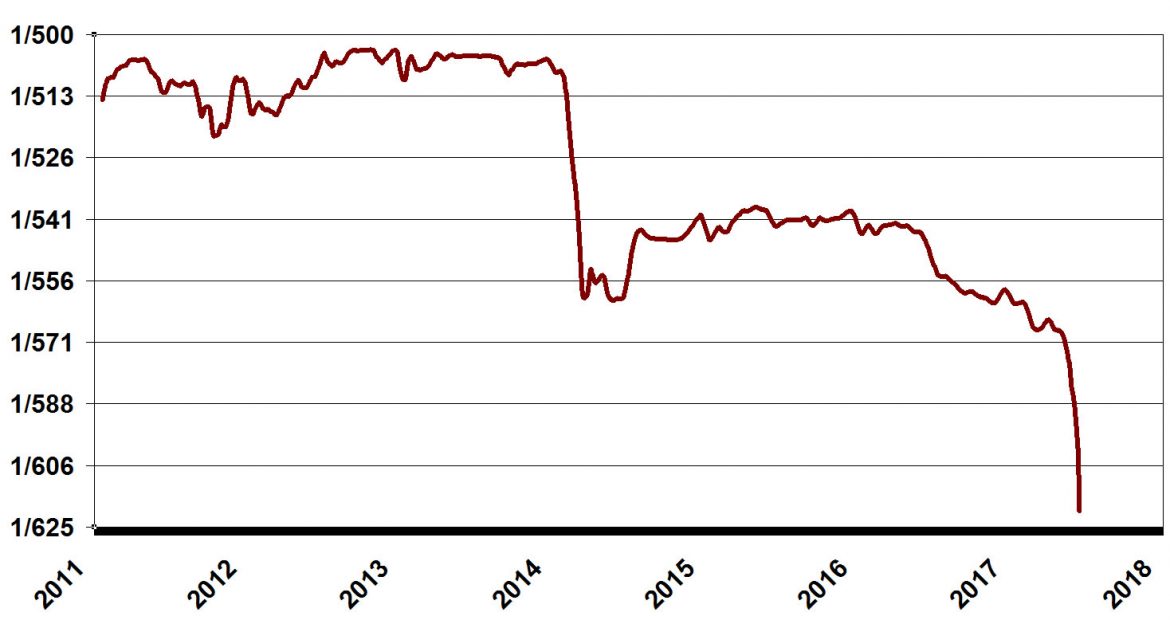

Now, after having neglected the problem for years, Costa Ricans suddenly find themselves sinking into a crisis that threatens to shatter this pristine international image. Yields on the government’s benchmark dollar bonds have soared to over 8 percent and the currency, the colon (pronounced col-ON), has been tumbling to record lows, prompting the central bank to boost interest rates last week to try to get investors to keep their money in the country.

The colon slumped 3 percent over a recent three-day period, a huge move in a country where officials have always tightly controlled its fluctuations. (Over the last three years, the average daily price move was just 0.007 percent).

“Costa Rica, after being given the benefit of the doubt, has started to feel the wrath of investors,” said Andrew Stanners, a London-based money manager at Aberdeen Asset Management.

Analysts worry that the losses could intensify quickly unless measures to rein in the deficit are implemented soon. And there’s another problem. The government isn’t the only one that was lured into borrowing in dollars. Over half a million Ticos, as Costa Ricans are called, have taken out dollar-denominated loans and mortgages, tempted by the prospect of paying interest rates that were about half of what they were in colons.

Like the government, these people are now scrambling to cobble together enough colons to buy the dollars they need to meet interest payments. Many are failing to. The percent of dollar-denominated loans in arrears climbed to about 3 percent in September from 1.7 percent a year ago.

Not only does this financial squeeze leave people with less money to spend on, say, a new pair of sneakers or a night-out at the movies — further crimping an economy that was already starting to slow — but it’s creating a sense of angst and dread in the capital city of San Jose that is palpable.

Pedro Cruz, a 38-year-old psychologist with a mortgage, two car loans and a business loan all in dollars, speaks warily about the idle speculation he hears from his friends. The colon will go into free-fall, they tell him, before throwing around wild numbers — 2,000 colons per dollar, maybe even 3,000.

These may be improbable forecasts but they scare Cruz, nonetheless. At today’s exchange rate, 620 per dollar, he’s already plunking down 60,000 colons more per month to meet his loan payments than he was just six months ago. He’s been shifting his savings into dollars to try to protect his finances. “I heard rumors of a devaluation and I decided to try and get ahead of it,” Cruz says. Unlike the colon, the dollar is always a strong currency, he says, and with it, “at least I can buy rice and beans for my children.”

The crisis deepened last month after a group of opposition lawmakers asked the Constitutional Court to rule on whether the fast-tracking procedure used to approve the fiscal reform violated the constitution. The legislation, which turns the sales tax into a value-added tax, closes loopholes and creates a capital gains tax, would have marked the first tax reform in two decades and reined in a deficit that has doubled in recent years to 7 percent of gross domestic product.

The court is expected to rule on Nov. 26, after which the bill would go back to Congress for a second vote. If the legislation earns final approval, the government plans to seek additional loans from multilateral banks to finance its budget gap. Finance Minister Rocio Aguilar said the government “will be ready” to deal with a possible defeat of the legislation though she gave no details on what measures would be implemented.

Costa Rica has burned through $1.6 billion of its foreign reserves over the last eight months — the result of its defense of the colon in the foreign-exchange market and the Finance Ministry’s need for hard currency to make debt payments. They now stand below $7 billion.

The government’s debt load could reach more than 50 percent of GDP this year, according to Moody’s Investors Service, which put the country’s sovereign rating on review last month for a possible multi-notch downgrade. And the central bank estimates that figure could breach 100 percent within a decade.

About 40 percent of the current debt load is denominated in dollars. The government has stopped selling debt abroad in recent years and been focusing on the local market instead. The problem, though, is that with the deficit swelling and the colon tumbling, investors are balking at buying local debt. At a debt exchange last month, the government only managed to sell 16 percent of the bonds on offer.

For years, the country had the “the luxury of time” to fix its problems, Aguilar said in an interview. “We don’t have that luxury anymore.”

Michael McDonald, Bloomberg