World News – Dahlia Schweitzer doesn’t technically identify Trump as a zombie fighter in her new book “Going Viral: Zombies, Viruses and the End of the World.” But her argument suggests that he’s caught in one of those undead narratives.

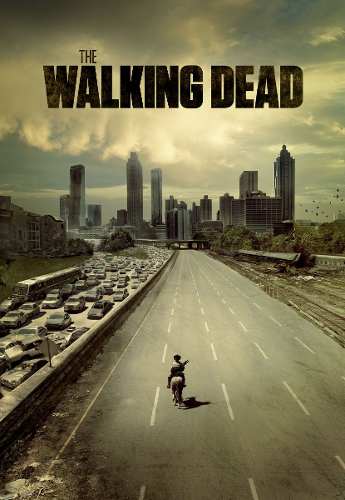

Schweitzer’s book looks at epidemic disease narratives over the last 20 years, starting with “Outbreak” (1995) and going through the current and never-ending zombie television apocalypse of AMC’s “The Walking Dead.” She concludes that these proliferating, infectious stories of disease have become intertwined with fears of globalization and our frighteningly interconnected world. Two decades ago, zombies were a minor horror genre; now the IMDB database has a list of the 50 most popular zombie films released in 2015.

Pop culture stories about infectious diseases have become more common, but also more focused on the global apocalypse. Without borders, we are unprotected and vulnerable. Which is also why, in Trump’s view, we need to start building walls. (Indeed, Trump heads to California on March 13 to get his first in-person look at wall prototypes in San Diego.)

Contagious disease narratives have been around for a long time. “Dracula,” featuring a diseased immigrant spreading terror and filthy infection, was first published back in 1897.However, Schewitzer argues, up until recently infection disease was depicted as having to travel very long distances, and as being fairly easy to quarantine. For example, Schweitzer points to the 1971 film “The Andromeda Strain,” in which scientists examine a dangerous virus from outer space in a secure facility underground.

“In ‘Andromeda Strain,’ everything’s on a very small scale in the town of Piedmont, which is a tiny little thing,” Schweitzer told me. “Then in ‘Outbreak,’ from 1985, you start getting this trajectory from Africa to the U.S. but it’s still focused, you can still follow the path of the virus when it spreads. And finally in ‘Contagion’ from 2011, within the first five minutes of the movie we’ve hopped all around the world and the virus is suddenly seemingly everywhere.”

Increasing fears of global contagion have a number of sources. The HIV epidemic in the 1980s, and the Ebola outbreak in the 1990s in particular stoked worries about new diseases. The 9/11 attacks spurred a new cycle of contagion fears focused on terrorist attacks, fears that found their ways easily into pop culture via shows like “24.”

Increasing fears of global contagion have a number of sources. The HIV epidemic in the 1980s, and the Ebola outbreak in the 1990s in particular stoked worries about new diseases. The 9/11 attacks spurred a new cycle of contagion fears focused on terrorist attacks, fears that found their ways easily into pop culture via shows like “24.”

More broadly, Schweitzer says, people have grown unsettled by an interconnected world in which factory jobs disappear and reappear, as if by magic, on the other side of the globe, while the internet beams anxiety-inducing news from every country on earth to your desktop.

Trump isn’t shy about making these connections between disease and globalization. In a meeting about immigration, he reportedly said that Haitians should not be allowed into the United States because they “all have AIDS.” Black and brown people, un-American others from somewhere out there, are dangerous, violent and disease-ridden. “He’s reinforcing this idea that immigrants are dangerous and they are dangerous because they will spread disease, rape our women, fill in the blank whatever you want,” Schweitzer told me. “And there’s this notion that if we just build a wall that’s tall enough we will finally be safe.”

Of course, if you’ve ever watched a disease or zombie film, you know there’s never a way to keep out the sickness or the zombie plague. Every seal fails, every wall is breached. As Schweitzer writes in her book, “Someone (a zombie, an infected victim, a terrorist) get out or something (a zombie, a virus, a bomb) gets in.” Or, as she told me, “You may think you’re safe but it’s inevitable that the virus is going to get in and the zombie is going to get in, it doesn’t matter if you’re in season three of ‘The Walking Dead’ and you’ve barricaded yourself in a prison, you’re still not safe.”

These failures are inevitable in part because the contagion in question is always impossibly dangerous. In real life, Schweitzer told me, an infection that kills its host would have a limited range, because dead hosts can’t spread a disease. Viruses can have high mortality or they can spread quickly; they can’t do both.

Yet during the Ebola panic of 2014, people panicked because a doctor infected with the disease had gone bowling and taken the subway. No one (not even the doctor) in that case died, but people reacted as if the nation faced a terrifying crisis. Meanwhile, Schweitzer points out, threats with a much higher death toll, like diabetes or gun violence, are treated as just part of day to day life. The real fear seems to be less of mortality, and more of invasion. We don’t mind if we die, as long as we’re not dying from something that came from over there.

The real contagion is just fear of contagion, and building walls and demonizing immigrants only makes that fear grow.

Many reporters and analysts have explained in detail why Trump’s border wall won’t actually keep immigrants out of the United States. But Trump’s wall isn’t about keeping immigrants out, not really. It’s about making sure that fear keeps getting in. Contagion narratives love breaches in the defenses because they are themselves breaches in the defenses.

Trump says he’ll restore American strength, health and purity, but the whole point of contagion narratives is that you can’t restore any of those things; the virus is spreading, and now terror and hate are let loose in the land. America elected Trump to keep out the zombies. But as so often in contagion stories, the supposed savior may actually be the source of the infection. You can’t build a wall to keep out the zombies when the wall-builder is the zombie-in-chief.

Noah Berlatsky is a freelance writer. He edits the online comics-and-culture website The Hooded Utilitarian and is the author of the book “Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics, 1941-1948.”

by Noah Berlatsky, NBCNews.com