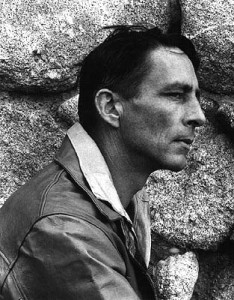

The cliché, ‘being ahead of one’s time’ is easy to say, and tedious to hear. But Robinson Jeffers was truly a poet ahead of his time. Yet his solution to the human condition always seemed too harsh, even inhuman to me. But it’s time to reconsider it.

Encountering a hermit on a wilderness trail, Jeffers reasserts a theme that runs through his body of work:

“Why do we invite the world’s rancors and agonies

into our minds though walking in the wilderness? Why did he want news of the world? He could do nothing to help or hinder.”

“Nor you nor I can…for the world. It is certain the world cannot be stopped or saved. It has changes to accomplish and must creep through agonies toward new discovery.”

“For each man there is a solution—let him turn from himself and man to love God. He is out of the trap then.”

That rings true, to a point. I have not felt it necessary to turn away from man to love God however, and that in fact to love God is love humanity. In other words, we cannot turn away from “the poor doll humanity,” as Jeffers puts it.

For are we separate from the world? Can we in any way separate ourselves from humanity?

Of course the world and humanity aren’t the same thing. Many ages and worlds have come and gone, and man has continued on his ever more destructive course. The human spirit survives, though the flame flickers.

So to turn away from this world may be necessary, and in fact some emotional and spiritual distance from it is essential merely to inwardly survive its horrors. But humanity is different matter.

The world cannot and should not be saved, but humanity must be saved. And the only way humanity can be saved, so that future generations can grow into human beings and fulfill Homo sapiens potential, is if some people give all they can to radically changing human nature, beginning but not ending with themselves.

Therefore the problem with Jeffers’ worldview is that it does not give succor, much less support to the work of human transmutation and revolution.

The world is in such a state of disorder at present it is often difficult to feel there is anything operating but darkness. So I understand why so many people have become atheists, and believe that there is no such thing as ‘the work.’ There are times I doubt it myself.

This world, I once heard someone say, breaks us all eventually. Before that happens to me, I’ll leave man and this world to their own devices. But can I?

The question I’ve held for over 30 years is this: Can the revolution in consciousness that changes the disastrous course of humankind ignite in my lifetime?

The evidence at present is no. Though as the saying goes, the absence of evidence is not evidence of absence–to a point.

The opening stanzas of Bryon’s last poem, “On this day I complete my 36th year,” comes to mind:

‘Tis time this heart should be unmoved,

Since others it hath ceased to move:

Yet, though I cannot be beloved,

Still let me love!

The fire that on my bosom preys

Is lone as some volcanic isle;

No torch is kindled at its blaze–

A funeral pile.

According to the poem, Byron despairs, flirts with self-pity, and then sees the bigger picture, before dying in Greece a few weeks later.

Perhaps in the end all one can do is contribute to the work of human transmutation, with no hope or expectation of seeing its culmination, as innumerable people in innumerable previous generations have done before us.

However Jeffers’ worldview does not even abide such notions:

However Jeffers’ worldview does not even abide such notions:

“Man’s world is a tragic music and is not

played for man’s happiness,

Its discords are not resolved but by other discords.”

Even so, the tightrope that a few feel compelled to walk is held taut by the question: Can the revolution in heart and mind that everyone from Jesus to Bernie (‘political revolution’—hah!) have worked to bring about occur now?

The question has no answer except in holding it as long as one can. And since one person cannot ignite a revolution alone, it’s a matter of knowing where one’s genuine limits are. But most people never test and stretch their limits, so they don’t ever find out what they’re capable of being and doing.

There comes a point where the only thing one can do is non-self-centeredly awaken intelligence to its fullest within oneself. That doesn’t mean the world’s problems cease to matter, or one’s problems cease to be. It just means that one ceases to suffer from them, because one observes without division and remains with what is without conflict.

When the only thing one can do to save humanity is to save oneself, that’s when one must let go of the work and whatever one’s task has been in serving it. For now though, for today, the question stands.

Martin LeFevre