Perhaps the biggest difference between Christianity and Buddhism is their respective philosophies and attitudes toward suffering. Christianity has enshrined it as ennobling; Buddhism decries it as unnecessary. The Buddhists are more right, but Christians aren’t entirely wrong.

What is suffering? Is physical pain part of suffering, or is suffering essentially psychological and emotional? How does suffering differ from sorrow? Is there really an end to suffering, or is it the human lot to suffer to one degree or another?

What is suffering? Is physical pain part of suffering, or is suffering essentially psychological and emotional? How does suffering differ from sorrow? Is there really an end to suffering, or is it the human lot to suffer to one degree or another?

The first mistake that most Westerners make about suffering is conflating man-made suffering with ‘acts of God.’ A tornado that slices through a town in the former heartland of America, killing a dozen people, produces devastation and grief, but not necessarily suffering.

The community may come together as never before and help one another; people may pass through their grief over losing a loved one; and injuries may heal without emotional scars. Suffering is what people generate before or after the fact of events and experiences.

Suffering covers too wide a territory in the West, and is mistakenly elevated, often with undertones of self-pity. These spiritual mistakes have their roots in an immature philosophy of suffering. Ancient India, epitomized by the Buddha, saw suffering very differently, as the primary condition of the human condition, the ending of which is the prime directive of an awakened life.

Thus the superficial notion that the Buddha taught that suffering is the first rule of life misses the mark by a mile. Though I’m not a Buddhist and haven’t studied Buddhism, I’m certain that Siddhartha meant something completely different. Indeed, he reportedly said, “I have taught one thing and one thing only, suffering and the cessation of suffering.”

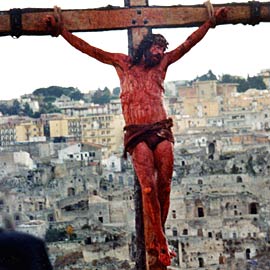

Much of the confusion about suffering in the West stems from the need to give meaning and purpose to the fate and  physical pain of Jesus, portrayed with pornographic violence in “The Passion of the Christ.” In the West, Jesus’ scourging and crucifixion came to symbolize the zenith of suffering and self-sacrifice, overlaid with the idea of a foreordained martyrdom termed ‘dying for our sins.’ That’s the last thing Jesus taught.

physical pain of Jesus, portrayed with pornographic violence in “The Passion of the Christ.” In the West, Jesus’ scourging and crucifixion came to symbolize the zenith of suffering and self-sacrifice, overlaid with the idea of a foreordained martyrdom termed ‘dying for our sins.’ That’s the last thing Jesus taught.

As I’m sure Jesus would point out, the Romans killed tens of thousands of people by crucifixion, sometimes thousands at a time, as they did after the slave revolt led by Spartacus. Most were killed not by being nailed to a cross, but by being tied to it, which took people much longer to die—days rather than hours.

Besides, the primacy of Jesus’ physical pain is the projection of our imagination and fear, rather than Jesus’ internal suffering, to whatever degree. Suffering is psychological. To the extent Jesus suffered at the end, it was undoubtedly because his mission went terribly wrong. But even that he came to terms, asking God to forgive people and surrendering himself to a higher intelligence.

My feeling is that, like Siddhartha, Jesus transcended suffering. Which doesn’t mean he didn’t feel great pain and sadness. Indeed, one’s capacity to endure pain, and absorb and go beyond sorrow (which is caused by the self but essentially collective), not personal, grows as one’s suffering lessens.

Suffering is therefore a continuity of unresolved experiences and emotions, a state of being rather than a transient state, like physical pain. Having experienced migraines that were off the charts when I was young, I found that the more that I allowed the pain to be, the less that I suffered from them. In other words, making the distinction between pain and suffering is crucial to diminishing both.

But ending suffering requires much deeper insight and understanding. Suffering is inextricably related to thought, fear, anxiety, and mental/emotional stress. When, while fully alive and awake during meditation, one enters the house of death without any morbidity, suffering and sorrow end. That’s as alien a truth as there is to the Western mind, but it’s one we can realize.

Magnificent oaks pepper the campus as well as the parkland in this locale, and some of them date back to the time when Native Americans lived here.

Even healthy Valley Oaks can be brittle, and in my years here, I’ve seen whole trees split down the middle, and once narrowly missed being struck by a sizable limb, as it suddenly and silently broke loose.

An Asian college girl was sitting in the courtyard of the high-rise dormitory on campus when a large branch of the oak suddenly fell, killing her. Classes had just begun in the new term, and the tragic incident has caused quite a ripple on the normally complacent party school.

An Asian college girl was sitting in the courtyard of the high-rise dormitory on campus when a large branch of the oak suddenly fell, killing her. Classes had just begun in the new term, and the tragic incident has caused quite a ripple on the normally complacent party school.

A few days after the event, I came upon two college students in the parkland, checking out the stump of the oak that I’d seen split down the middle one fine sunny day. I commented that a year ago, there had been what looked like a healthy tree on the stump where they stood.

They were new in town, and we talked about the incident at the college. “The college may be in for quite a lawsuit,” the fellow said. I replied that as terrible a thing as it must be for the family of the young woman, it didn’t sound like there was any negligence on the part of the college.

There’s an expression, “the earth has nothing more beautiful than a tree.” Yet a tree killed what from all accounts was a lovely young woman who helped everyone that asked, and was in college to become a nurse. Was it ‘an act of God?’ I doubt there is such a thing where nature is concerned, except as the phrase has come to mean—a freak accident, a random event.

Some things we can never know. But as far as suffering goes (and it goes very deep and wide), our thoughts and emotions, however dark or troubling, have to be allowed to flower in freedom, without reacting to or from them. In flowering they die, and we are liberated from suffering.

As Siddhartha said, “There are only two mistakes one can make along the road to truth; not going all the way, and not starting.”

Martin LeFevre