There’s a lot of interest in human origins these days. A permanent exhibition, featuring more than 200 casts of pre-human and human fossils at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, addresses three fundamental questions: Where did we come from? Who are we? And what lies ahead for us?

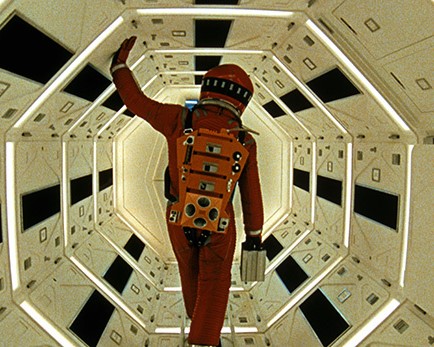

In the classic movie, “2001: A Space Odyssey,” Arthur Clark’s story and Stanley Kubrick’s film address the same three questions. It presents, in cinematically symbolic terms, a coherent theory of human nature.

In the classic movie, “2001: A Space Odyssey,” Arthur Clark’s story and Stanley Kubrick’s film address the same three questions. It presents, in cinematically symbolic terms, a coherent theory of human nature.

The movie opens with a large, black monolith surrounded by a group of apes. They are displaying innate curiosity, cautiously inspecting and touching the strange object. The monolith remains in the apes’ midst until the right moment, symbolized by the alignment of the sun and moon. Then it silently triggers a momentous insight in one of the apes.

To the soaring notes of Strauss’ “Also Sprach Zarathustra,” one of our theoretically proto-human ancestors pauses amidst a field of animal bones, and has the ‘aha’ moment of all moments. He picks up a thighbone and begins smashing skulls with it, first a fleshless skull amidst the field of bones, then the living animal (signifying the beginning of hunting), and finally, the skull of a rival group member (signifying the beginning of war).

The weapon is tossed into the air, and morphs, millions of years later into the graceful arc of a rectangular space station, famously set to the Blue Danube Waltz. As this and other technological marvels soar through space, the message is clear: all our vaunted technology sprang from that first insight and lethal tool.

“2001” unfolds as a montage of evolutionary culmination and human alienation. The monolith appears again on the moon during an excavation that still seems futuristic in 2016. It was buried by some unseen intelligence, with perfect placement and timing, to be discovered by the distant descendents of the skull-smashing ape. The mysterious object emits another signal, this one painfully audible, which directs humans of our time to a point near Jupiter.

A grand mission is undertaken, but HAL, the superhuman computer brain in charge of all functions on the spaceship, goes haywire, and an epic confrontation between man and machine ensues. Once that test is passed, the surviving human completes the journey alone, both his hibernating and ambulatory compatriots having been snuffed out by HAL.

Near the end of “2001” there is a wonderful riff on time, with past and future converging in the present and telescoping into each other.

The sole remaining astronaut, having been transported into another dimension (symbolized by the psychedelic scenes for which the movie is famous), first sees himself as an old man, looking back at the young man. Suddenly he is the old man, seeing himself on his deathbed.

Then he is on his deathbed, and there’s a breakthrough. A new human being is born, floating in space next to the earth, its amniotic sac having a larger circumference than the earth itself.

With a stroke of perhaps unintended artistic genius, Kubrick conveys in these scenes something of the essence of the meditative state, compressing all psychological time and human experience into an infinite regression that leads to a breakthrough to a higher order of being.

“2001” provides one possible answer to all three questions posed at the beginning of this column. For a boy of 16, imagination fired by the early NASA missions, the film launched my philosophical vocation.

The essential flaw in the book and film, and my point of departure with it as a young man given to non-drug-induced ‘mystical experiences,’ is the positing of an outside force prompting human evolution at critical junctures. That smacks of divine intervention.

There is no outside force; the mystery is much greater and deeper. But “2001’s” portrayal of the crisis of humankind’s alienation from nature and ourselves is penetrating and prophetic.

The film is correct in implying that there is another stage of human evolution. And it was prophetic in showing the inverse relationship between man’s expanding technology and shrinking consciousness.

The latest example of silliness of the standard model of human progression, which positively links science/technology and consciousness, is Stephen Hawking, Mark Zuckerberg and others’ plan to laser-shoot fleets of nano-robots to Alpha Centauri. It’s called, oxymoronically enough, “Breakthrough Starshot.”

“What makes human beings unique?” Hawking gamely philosophizes. “I believe that what makes us unique is transcending our limits,” is his lamely reply. Ok, but sending an army of robotic ants to the nearest star system has the opposite effect here on earth. By compulsively defining our limits externally, the reductionism of science is reducing the human mind and spirit.

“2001” had far more insight and imagination, accurately inferring that the further humans have progressed scientifically and technologically, the more alienated from nature and hubristic in the cosmos man has become.

The obsessively outer orientation of science and technology is becoming more and more ludicrous in the face of human fragmentation and disorder. The intensifying crisis of consciousness, now felt everywhere in the world, delineates the actual human limitation that has to be transcended.

Something has to give, and the big brains of science and big bucks of technology are not pointing the way ahead.

The true frontier lies within. In a universe ‘fine-tuned’ to evolve conscious beings with brains capable of awareness of wholeness and the cosmic mind, why is it so difficult to transcend the planet-plundering limits imposed by symbolic thought and denied by scientific minds?

Martin LeFevre

Trailer to “2001, A Space Odyssey”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XHjIqQBsPjk