In the deeply battered and bereaved central African nation of the Democratic Republic of Congo, the United Nations has formed an “intervention brigade” that’s taking proactive measures against rebel groups. The shift is seemingly small, but has profound implications for global policy.

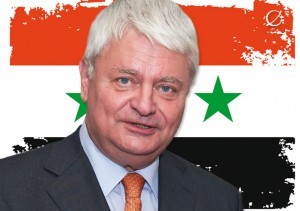

Facing criticism for this approach while in Paris attending Independence Day celebrations, UN peacekeeping chief Herve Ladsous responded sharply.” How can you be neutral or impartial to those terrible armed groups who have been for years now, a decade or more, killing civilians, raping women, recruiting child soldiers? No, you cannot be neutral.”

Facing criticism for this approach while in Paris attending Independence Day celebrations, UN peacekeeping chief Herve Ladsous responded sharply.” How can you be neutral or impartial to those terrible armed groups who have been for years now, a decade or more, killing civilians, raping women, recruiting child soldiers? No, you cannot be neutral.”

Unbeknownst to the rest of the world, or at least the universe-unto-itself that is America (except for our government of course, which has its military mitts in a thousand places, most of which the average American has never heard of), the UN has been in eastern Congo for over a decade, part of a MONUSCO (don’t ask) force charged with peacekeeping.

Of the millions of people that have died in 20 years of hellish conflict involving God knows how many parties and patsies, hundreds of thousands have perished since the ineffective UN force was first deployed. No place on earth, except for Syria, has sucked whatever life was left out of the United Nation’s core mission and spirit after 9.11 more than the Congo.

Most of the troops for the new, 3000 strong ‘intervention brigade’ come from Tanzania and South Africa, and are already in place. Tanzania, led by Julius Nyerere, is revered for its ouster of the psychotic slaughterer Idi Amin in 1979, stepping in when the ‘international community’ sat on its hands, like it has done the last two years in Syria.

With bitter irony, the United Nations signed an agreement last Friday with an unnamed drone company that would allow for a “complete picture of what is happening on the ground.” “We have just signed a commercial contract for the UAVs, and I say UAVs, not drones, as they are unarmed,” Ladsous said.

Three things combine to produce a high wretch factor in this statement. First, the use of drones, armed or unarmed, follows in the wake of America’s failed take-no-prisoners anti-terrorism policy, which has added far more insecurity to the world.

Second, also following the American model, the agreement was signed with commercial contractors, not, as one  would expect, with the affected and afflicted nation of the Democratic Republic of Congo itself.

would expect, with the affected and afflicted nation of the Democratic Republic of Congo itself.

And third, the idea that unarmed drones, sold and no doubt manned by a commercial company, can give a “complete picture of what is happening on the ground” is ludicrous on the face of it.

The feckless ‘international community’ has no trouble intervening and experimenting with an underdeveloped African country characterized by thick forests, rugged terrain and few roads. But it cannot muster the political will, humanitarian conscience and strategic imagination to prevent a hundred thousand people from being killed and an ancient civilization in Syria from being ripped to shreds.

After the evil of Bashar al-Assad, and the complicity of the Russians, the atrocity of Syria sits squarely on President Obama’s shoulders. The world looked to him to lead following the debacle of George Bush in Iraq, but he didn’t even try.

Syria is a completely different case than the ‘war of choice’ in Iraq. The US didn’t have to intervene, pick sides, or be a party to its militarization; it had to act to prevent a clearly foreseeable and preventable slaughter. History will judge Obama and America harshly, and already is.

U.N. peacekeeping principles stipulate impartiality and “non-use of force except in self-defense and defense of the mandate.” Ladsous, unintentionally pronouncing (since he meant it to apply only to Congo) a profound shift in philosophy without any shift in policy, cavalierly said, “neutrality, impartiality: that is the case for classic peacekeeping.”

For ‘international law’ to have any real meaning, the concept of sovereignty has to undergo a radical redefinition.

There are two principles and premises that the international community will have to come to sooner or later (hopefully sooner rather than later) if effective global governance (not global government) is to ensue.

The first is that social and political sovereignty (literally, the supreme factor) is now humanity as a whole, not the logical and unworkable state of affairs of nearly 200 sovereign nation-states.

The second is that in a global society ‘the internal affairs of nations’ are no longer sacrosanct. ‘Internal’ and ‘external’ have become fluid notions.

That doesn’t mean that more powerful states have a right to interfere in less powerful ones, as is now the case. Nor does it mean, as the United States, China and Russia fear, that the ‘international community’ will be able to supersede their rightful national authority.

It simply means they, as all nations, must be held to common standards of human conduct, inside and outside their borders.

Martin LeFevre