A large, brown, stipple-winged hawk takes off from the path ahead of me with some small animal in its mouth. It’s near dusk, and the parkland is full of Cooper’s hawks.

Another hawk, perched on a branch overhanging the park road, drops from the limb and screeches continuously as it glides in a straight, level flight path just above the road ahead. A few minutes later, two people walking in front of me stop and turn to watch a raptor alight high in a sycamore tree.

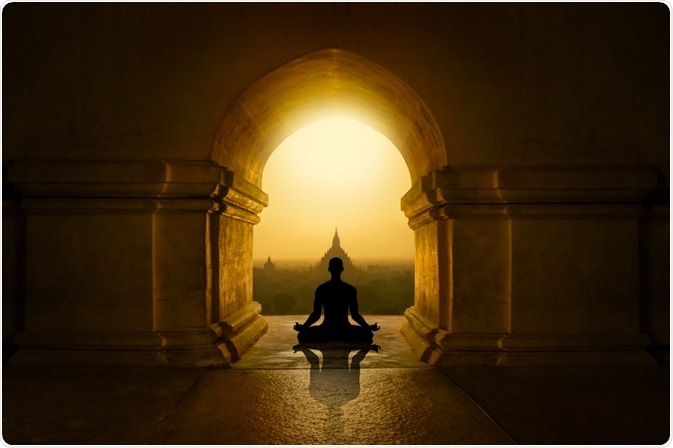

Later, for the last 20 minutes during a meditation by the stream, a gray squirrel chatters away in a tree behind me. Consciousness is like that squirrel prattling on. It isn’t concentration, but inclusive, undirected attention that quiets the mind.

A hundred meters up the path I pass two college-age couples talking non-stop as they imbibe at a picnic site adjacent to the footbridge. In the time it takes me to go by, one of the young women changes subjects about shopping three times, without appearing to take a breath.

Meditation – the spontaneous quieting of thought — cannot truly begin until the mind/brain lets go of everything. No trick or technique can cause it to do so. Only undivided observation loosens the bonds and ends the grooves of thought.

Why is it so difficult to let go? What is it about the human mind that keeps us attached to beliefs, people and problems? It appears as though the brain, using thought, is wired to attach itself to things.

Attachment is in the nature of thought. Obviously attachment is also a function of the self, which is a fabrication and creation of thought. And as long as there is the emotionally held idea of a separate self—me, my and I—there will be attachment with all its problems.

Clearly, there is no separate entity that stands apart from anything. Why then is there a seemingly separate self that experiences things as happening to it, rather than simply happening? Why isn’t experience perceived as an unbroken flow of inner and outer movement, but seen instead in terms a fixed center?

Is an illusorily separate self that interprets, judges, evaluates and then acts an unchangeable part of being human?

No, the operating system, program and contents of the self fall away during meditation. And when there is no sense of self, there is no basis for attachment. Therefore attachment, and all the suffering it engenders, is a function of the ‘me,’ the emotionally embedded ego at the center of human experience.

The expression, ‘my thoughts,’ is not merely redundant; it is existentially and neurologically erroneous. And yet the ‘me’ seems to have tremendous validity.

Though the separate self doesn’t actually exist, the brain, dominated by thought, fabricates a separate self, and holds onto it for dear life. This ancient habit of the human mind then extends to ‘my country,’ ‘my religion’ and ‘my group,’ though such arbitrary divisions generate incalculable death and destruction.

In the absence of insight into the nature of thought, which evolved for utilitarian separation of ‘things’ from the environment, the mechanism of a separate self is constructed to bring some semblance of order and stability to the chaos of thought.

The brain records experience, and a program called ‘me’ subconsciously selects and screens, according to one’s conditioning, what it subconsciously deems important. Awareness can be quicker than thought however, and bring subconscious habits and unconscious content into the light.

Apparently as humans evolved conscious thought, the survival instinct became linked to concepts of identity, and identity then became imbued with the importance of survival.

So instead of realizing that I am thought, there is the subconscious and emotionally held idea that ‘I am not thought, but a separate entity, ‘me’.’

From this psychological basis, the idea of permanence, and the fear of death, are inevitable. So separate selfhood, survival, attachment, permanence and fear of death got mixed up together, and formed the psychological basis of our dubious humanness.

Thought-dominated consciousness has become utterly dysfunctional however, both individually and collectively.

Authentic meditation, which has nothing to do with methods, techniques and traditions, awakens another order – a true order — of consciousness.

To ignite meditation, one has to begin by ending division in observation. In actuality, there is no observer or watcher. By passively observing the observer and watching the watcher, awareness quickens and gathers force. In the unwilled and undirected attention that ensues, attention, in itself and by itself, halts the habit of psychological separation, if only for a few precious, peaceful minutes a day.

Thought is a single stream, which habitually separates us from nature and humanity. When the sense of separateness ends, thought simply falls silent, and there is “the peace that passes all understanding.”

That’s the meaning of meditation. And by whatever name one gives it, it is the single most important, and urgently necessary action for the individual, and for society.

Martin LeFevre