About a dozen vultures are circling lazily in a gentle breeze over the gorge in the relatively unspoiled canyon of Upper Park. They are graceful searchers for gruesome remains. Without the associations that go with the word vulture, they are seen as they are. There is no ugliness in nature, only in man.

It’s an unseasonably warm afternoon, even in northern California. A quarter mile from the parking lot, I pass a couple sitting in large lawn chairs, complete with drink holders, books, music and other paraphernalia.

It’s an unseasonably warm afternoon, even in northern California. A quarter mile from the parking lot, I pass a couple sitting in large lawn chairs, complete with drink holders, books, music and other paraphernalia.

The hour-long hike is wondrous, with grand views of the cliffs on both sides of the canyon and gentle slopes stretching toward the horizon.

Sitting on the ground at the lip of the gorge for over an hour, I don’t see another soul. The vertical slabs are stained with ochre, and subtle shades of yellow and red run down many of the rock faces.

A few vultures glide down the gorge below eye level, only a few meters away. I can see their vigilant eyes in their red heads, and each of the long feathers that protrude from the ends of their wings like delicate fingers.

As the mind completely quiets and meditation deepens, the sight of the angular, colored rocks evokes not merely centuries, but millennia, including the long and tortuous history of man.

What is a human being? Isn’t a human being a person capable of having a brain that is completely and effortlessly quiet, one who has a mind that can totally set aside the movement of thought, knowledge and experience, and be alight with insight?

Is such a human being realizing the cosmic intent, an intent that is without a deity, plan, or pre-design? Is that intent intrinsic to evolution, inherent in the development of galaxies, stars, planets and life forms?

Aristotle laid out the grid for the Western mind. And with the ending of a distinctly different Eastern mind in recent decades, it has become, for better but mostly worse, the world mind.

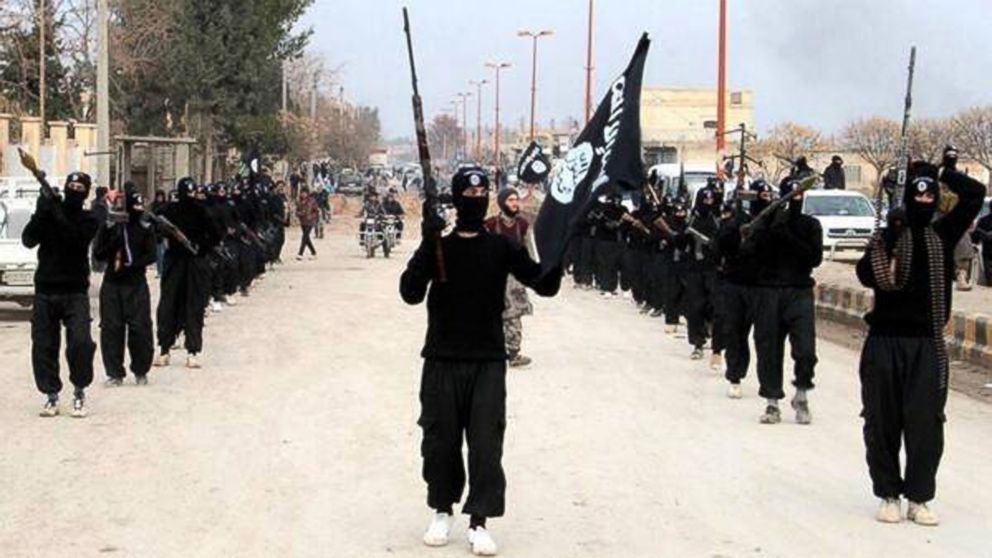

Modern science is the zenith of Aristotle’s underlying framework, but Western civilization’s pervasive and globalizing meaninglessness is its nadir. The Arab world has lost its identity, and at bottom al Qaeda and ISIS murderers are raging  against the Western mind.

against the Western mind.

Therefore the conflict is not between the Islamic and Christian worlds. Humankind is facing a total and unprecedented crisis. Religions, traditions and institutions are incapable of meeting the present challenge, because the collapse goes beyond these expressions of different cultures to the core of human consciousness itself.

The task before philosophy now is to expose and erase the Western grid, without diminishing the scientific enterprise, and bring about a new mind. Philosophy can and must point the way, but radical change begins and ends within the individual. Right observation of the movement of thought/emotion opens space and insight in the mind of the undivided human being.

Scientific knowledge does not satisfy humankind’s sense of wonder; it is diminishing it in almost everyone except the scientists making the discoveries. The clearest but most unacknowledged revelation from the explosion of scientific knowledge is that knowledge does not bring about understanding and wisdom.

There are of course rational and irrational forms of knowledge. But I’m not making the usual philosophical distinction between scientific and other types of knowledge. I’m saying that insight, understanding and wisdom are not a function of knowledge of any kind.

Pursuing scientific knowledge for its own sake, or for the betterment of humanity, is a good thing. Making knowledge the highest good however, much less the be-all and end-all of human life, means heading in the wrong direction, the direction that Aristotle and other ancient Greeks set. Though the ancient Greeks made modern science possible, they were mistaken to give knowledge the highest priority.

The idea that scientific knowledge, or any other kind of knowledge (theology for example), can answer all questions and solve all problems is a product of human hubris. A complete explanation of the origin and meaning of life is an unattainable goal. Scientifically, there will always be more questions; spiritually and philosophically, questioning never ends, even in illumined human beings, which I’m not.

The first and most urgent question is the contradiction between man and the movement of nature. Nature unfolds in wholeness and man is fragmenting the earth, producing the mass extinction of other species and the destruction of the viability of ecosystems. Though few philosophers and fewer scientists are interested in that core conundrum, there is an adequate explanation for it. But the explanation won’t change the explained—you and I.

Therefore, while we should always seek rational explanations, we must never be satisfied with them. Knowledge can never be complete, and wonder, mystery and reverence for life flow from a completely different source, which can only be experienced when we see the existential limits of knowledge.

Martin LeFevre