To most Americans, metaphysics, if they give any thought to the subject at all, appears as it did to the first pragmatist philosopher, William James: “As in the night all cats are gray, so in the darkness of metaphysical criticism all causes are obscure.”

However the word metaphysical can refer to the vast unexplored territory of the mind and consciousness, which includes any phenomena not amenable to scientific knowledge. There are an unlimited number of mysteries that science can explain, but science can never explain and encompass mystery itself.

Therefore I beg to differ with the great philosopher Donald Rumsfeld, who infamously said, “There are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns — the ones we don’t know we don’t know.”

Hilarious as that is, it was uttered during the deadly serious business of the Bush Administration’s murderous and mercenary invasion of Iraq. Rumsfeld himself, like most conservatives (and liberals for that matter), falls into his last category with regard to himself: “we don’t know we don’t know.” That is to say, he unwittingly spoke to an utter lack of self-knowing.

To my mind, epistemology is both simpler, and much more difficult comprehend than Rumsfeld’s metaphysics. There is knowledge—the accumulative content of science and skill; there is the known—what we overvalue as experience; and there is the unknowable—for which only silence will suffice.

Long before modern philosophy’s specializations and confusions, Western philosophy took root in ancient Greece during what’s called the Milesian period, from about 600-528 B.C. with Thales, Anaximander and Anaximanes.

In reading about them, I came across a sentence that embodies the arrogance of our age: “Since these men were pioneers in philosophical and scientific endeavor, it is only natural that their findings, and the language used to express them, were primitive.”

Conflating “philosophical and scientific endeavor” is a big mistake; it marks the point where modern philosophy made a wrong turn.

To be sure, scientific findings, and the language used to express them, were primitive in ancient Greece. But it’s hubris to not realize that scientists in 2500 years, if humankind survives this Dark Age, will say the same of scientific findings today.

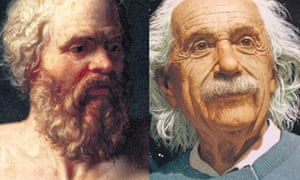

Even with big paradigm shifts, such as from Newtonian to Einsteinian to quantum physics, science grows increasingly accurate in its accumulation of knowledge. But philosophical insight is completely different than scientific findings.

For one thing, the accumulation of knowledge does not apply. Philosophy is not a function of knowledge, of obeisance to what came before, as it inquires into the truth.

So philosophy, much less metaphysics, isn’t about knowledge at all. It’s about insight, understanding and wisdom. That means the insights of Thales, if they were true insights, were just as accurate in his day as their rediscovery (irrespective of Thales) would be today.

The basic malady of our age began with not distinguishing, without division and specialization, between the scientific, philosophical and religious minds. They can overlap, and grow harmoniously within the individual, with different emphases for different individuals. (The religious mind has little or nothing to do with religions by the way.)

Since the so-called Enlightenment, and especially since the breakthroughs in physics in the early 20th century, philosophy took a back seat to science, and then tried to ape it. In the process, philosophers have marginalized themselves in the ivory towers of academia.

In truth, science and philosophy, much less science and the inner life, are distinctly different endeavors. The challenge before us now, as the modern world of reason and science, Locke and democracy collapse around (and within) us, is to make the distinctions clear and create new harmonies.

Life is essentially unknowable and mysterious. Science is able to resolve mysteries, but in the process it has been destroying people’s sense of mystery. And to grow as human beings we have to feel the deeper sense of mystery.

Science and technology at present are permeated with hubris. Human knowledge and experience is but froth and foam on the torrential stream of the universe. Awareness of that fact waters another crucial seed in the growing human being—humility.

When we acknowledge and embrace life’s essential mystery, while still questioning philosophically, and working to resolve mysteries scientifically, we have both a religious mind and a scientific mind. Then we’re aligned with life, at peace within ourselves, and able to use scientific knowledge with wisdom.

The ancient Greeks, and particularly Thales, had a word for the unknowable, the boundless and infinite. He called it the apeiron. It’s high time at this low tide in human history that we restore the feeling of the apeiron within us.

Martin LeFevre

Lefevremartin77 at gmail.com

Fountainoflight.net