Humanity’s place in the universe is one of the great-unanswered questions of philosophy and science. The search remains compulsively outward and external however. I maintain the answer is first within.

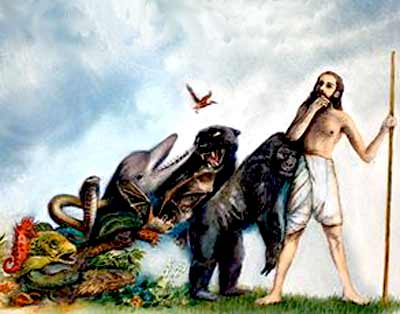

It stands to reason that to understand our place in the cosmos we first have to understand why Homo sapiens doesn’t fit on earth. In the last 30 years however, there has been a systematic attempt to show that humans aren’t fundamentally different, and are inextricably part of nature.

It stands to reason that to understand our place in the cosmos we first have to understand why Homo sapiens doesn’t fit on earth. In the last 30 years however, there has been a systematic attempt to show that humans aren’t fundamentally different, and are inextricably part of nature.

Because second part of that equation is indisputably true, and because the program to gloss over human disconnectedness and destructiveness has been largely successful, we have failed to understand what makes us different from every other animal that has ever walked, crawled, swam or flew on this exquisitely blue marble in space.

Part of the reason for blurring the difference between humans and other animals is an attempt to offset the idea of man’s special creation in Genesis, which still holds sway over many Christians. We can’t have it both ways however. Though the fact of evolution repudiates man’s special creation, the fact of man’s separation from nature cannot be rubbed out by shared evolution.

In a phrase, what makes humans separate from nature is that we are the only species that separates ‘things’ from nature. There are no ‘things,’ except as the mind of man conceives them. The evolution of symbolic thought was therefore both a gift and a curse—for the human species, and the earth itself.

The human adaptive pattern doesn’t just mean that humans are smarter than any other animal (though many animals display surprising smarts in their own right), but that only Homo sapiens depends on detaching animals, plants and minerals from the environment and mentally rearranging and recombining them for its use.

Utilitarian separation would not be a problem except that it leads to psychological division. Humans are separate from nature because thought, which is based on separation, does not know its place and cannot be still.

This is the root of man’s disconnectedness from and destructiveness in nature, and with each other. When humans lived close to nature, we were reminded on a daily basis that we aren’t actually separate. Indigenous people developed myths, traditions and rituals that were coherent and cohesive. But now all constraints on thought’s divisive and fragmenting tendencies are off.

Instead of insight into the human contradiction and conundrum, we being fed obtuse and anthropocentric stuff like this statement by Raymond T. Pierrehumbert, a climate scientist who was recently appointed the Halley Professor of Physics at Oxford University:

“For all we know, we may be the only sentience in the Galaxy, maybe even in the Universe. We may be the only ones able to bear witness to the beauty of our Universe, and it may be our destiny to explore the miracle of sentience down through billions of years of the future, whatever we may have turned into by that time.

Egad that’s bad. It continues to place the human species at the center of creation, substituting evolution and chance for special creation and ‘intelligent design.’ It downplays the real and present danger of ecological collapse brought about by the stupid use of ‘higher thought’ (which is  actually a crisis of consciousness itself), and it veritably worships the mind of man.

actually a crisis of consciousness itself), and it veritably worships the mind of man.

Pierrehumbert does talk about climate change, though in absurdly understated tones, when he says, “we have to make it through the next two hundred years first, and this will be a crucial time for humanity.”

But he quickly returns to his main view of humankind, expressed in the treacly statement that “it is beyond awesome that we little lumps of protoplasm squinting out at the Universe from our shaky platform in the outskirts of an insignificant galaxy can, after four decades of indefatigable effort, detect and characterize a black hole merger over a billion light years away.”

Is it really necessary to point out that the earth has only become a “shaky platform” because the human species has made it so? Is it really necessary to point out that the human body (“little lumps of protoplasm”) isn’t significant, but the human brain, the most complex ‘thing’ in the known universe, reflects ongoing creation in the universe when the mind-as-thought is silent?

The human mind doesn’t make humans important, much less the center of anything, but the human brain does imply a true mystery and miracle—that awareness of beauty and sublimity, and the evolution of neuronal capacity go hand in hand.

And this awareness, which doesn’t arise from and isn’t confined to the human skull, is immeasurably more significant in this “insignificant galaxy” than the ability to detect black hole mergers in a distant one.

Martin LeFevre