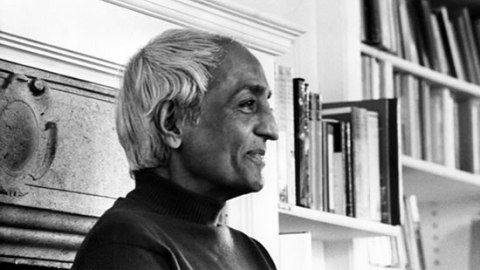

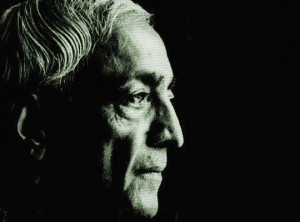

This is the story of how the teachings of an illumined teacher are turned into groupthink by his followers, which in turn become the basis for another religion. I’m referring to the worldwide network that formed after Jiddu Krishnamurti’s death in 1986.

Seeming contradictions about Krishnamurti’s life have emerged since his death, and there are basic questions about the framework, organization and people surrounding ‘the teachings.’ But Krishnamurti’s teachings themselves remain the clearest expression of psychological and spiritual truth I’ve read and of which I know.

Seeming contradictions about Krishnamurti’s life have emerged since his death, and there are basic questions about the framework, organization and people surrounding ‘the teachings.’ But Krishnamurti’s teachings themselves remain the clearest expression of psychological and spiritual truth I’ve read and of which I know.

Krishnamurti was born at the end of the 19th century, when Theosophy was all the rage in England, America and India. Theosophy had and still has some serious elements, but it became associated with all manner of occult mumbo jumbo in the early part of the 20th century. It was fixated on the ‘Ascended Masters’–realized beings that allegedly incarnated into human beings.

(Whether there is any validity to Theosophy’s claims of esoteric knowledge is not my concern here. I take an agnostic attitude, as reflected by Shakespeare’s Hamlet: “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than dreamt of in your philosophy.”)

Though it would be decades before Indians threw off the chains of the British Empire, an early and effective English advocate of Indian Home Rule was Annie Besant, who was president of the Theosophical Society after its notorious Russian founder, Helena Blavatsky.

Krishnamurti was ‘discovered’ by Besant’s cohort, an unsavory character named Charles Leadbeater, when Krishnamurti was walking the beach at Adyar India with his younger brother. Leadbeater, who supposedly had the power to instantly read auras, said the 11-year-old Krishnamurti had the purest aura he’d ever seen. Krishnaji, as he came to be affectionately known, was one of eight children in a poor Brahmin family whose mother had died a few years earlier. Leadbeater and Besant took in Krishnamurti and groomed him to be the  “World Teacher.”

“World Teacher.”

After coming of age, Krishnamurti displayed tremendous integrity and courage by renouncing his role in Theosophy as head of ‘The Order of the Star,’ declaring, “You can form other organizations and expect someone else. With that I am not concerned, nor with creating new cages.”

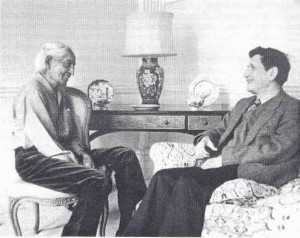

‘K’ went on to give extraordinarily clear and passionate talks around the world for over 60 years on the human condition as it pertained to and was contained in the individual. Paradoxically, he thereby became a world teacher, strongly influencing people like Deepak Chopra and Eckhart Tolle.

The essence of K’s teachings remained the same throughout the decades of his speaking, and can be summed up in the statement he made in the late 1920’s, during which he broke with Theosophy: “Truth, being limitless, unconditioned, unapproachable by any path whatsoever, cannot be organized; nor should any organization be formed to lead or to coerce people along any particular path.”

When it was all over, and Krishnamurti lay dying from pancreatic cancer in Ojai California at age 93, he said, “No one had understood.” But he also said, “Don’t interpret; protect the teachings.”

It’s ironic, though perhaps not surprising, that those who knew Krishnamurti and those that came into the ‘K world’ after his death, seem to have done exactly the opposite—interpreting ‘K’s’ message along the lines of their mediocrity, and instituting a groupthink bordering on cultishness. So much so that it makes one doubt whether the entire project was fundamentally flawed from the beginning.

‘K people’ tend to be smart and intellectual, skilled at the very casuistry and sly tricks of thought that Krishnamurti deplored. As one of the two people present at Krishnamurti’s death said to me, “People are unfortunate; K people are more unfortunate than most.”

When ‘K people’ are asked about the apparent gulf between the teacher and his followers (they bridle at the term followers, but the shoe fits), they invariably say things like: “Groupthink does not seem to be a problem with ‘K’ folks any more than any other group of people; besides, groupthink is almost always present, to some extent, in any gathering of two or more people.”

When ‘K people’ are asked about the apparent gulf between the teacher and his followers (they bridle at the term followers, but the shoe fits), they invariably say things like: “Groupthink does not seem to be a problem with ‘K’ folks any more than any other group of people; besides, groupthink is almost always present, to some extent, in any gathering of two or more people.”

Failing to hold to a higher standard than “any other group of people,” while at the same time saying things like, “I attribute the flowering I detect in me to Krishnamurti’s teachings” reflects the maddeningly cunning habit ‘K people’ have of having things both ways. Groupthink is not thinking together.

My doubts stem from Krishnamurti creating a worldwide organization to disseminate ‘the teachings,’ after decrying organized religions for decades. It begs the question: Does the parlous condition of the Krishnamurti network stem from a flaw in the man and ‘the teachings’ themselves, or from the very thing he warned about–personal interpretation rather than living inquiry and insight?

Again, though there seems to be contradictions about Krishnamurti’s life, he apparently lived ‘the teachings’ to an extraordinary degree, as this passage from “Krishnamurti’s Notebook” attests:

“Waking towards dawn, meditation was the splendor of light for the otherness was there, in an unfamiliar room. It was an imminent and urgent peace, not the peace of the politicians or of the priests nor of the contented; it was too vast to be contained in space and time, to be formulated by thought or feeling. It was the weight of the earth and the things upon it; it was the heavens and beyond it. Man has to cease for it to be.”

Krishnamurti, in breaking with Theosophy, famously said, “My only concern is to set men absolutely, unconditionally free.” He certainly did not achieve that in his lifetime. Indeed, humans are much darker and more enslaved to the past and programming than they were at Krishnamurti’s death.

Though most educated people still deny it, cleverly evading the issue with rationalizations like, ‘people have always egotistically thought that their time was the end of the world,’ it’s irrefutable that humankind is regressing inwardly in inverse proportion to the outward progress of science and technology.

As darkness and deadness engulf the human spirit, the New Age movement, owing to no small, if inverse and perverse influence from Krishnamurti’s teachings, skates along on the surface, giving new meaning to solipsism and self-absorption.

Even so, Krishnamurti’s teachings could take their place at the forefront of the ancient ‘perennial teachings’ and the work of human transmutation—if more than a few begin doing the work within, and think together.

As the crisis of consciousness Krishnamurti so often and passionately addressed intensifies, the human mind does not need a new religion; religions need a new human mind.

Martin LeFevre