Travel & Tourism – With self-driving cars and trucks coming on fast, it’s only natural to wonder if self-flying planes might be next. In fact, the aviation industry is pushing to make autonomous passenger aircraft a reality — and sooner than you might think.

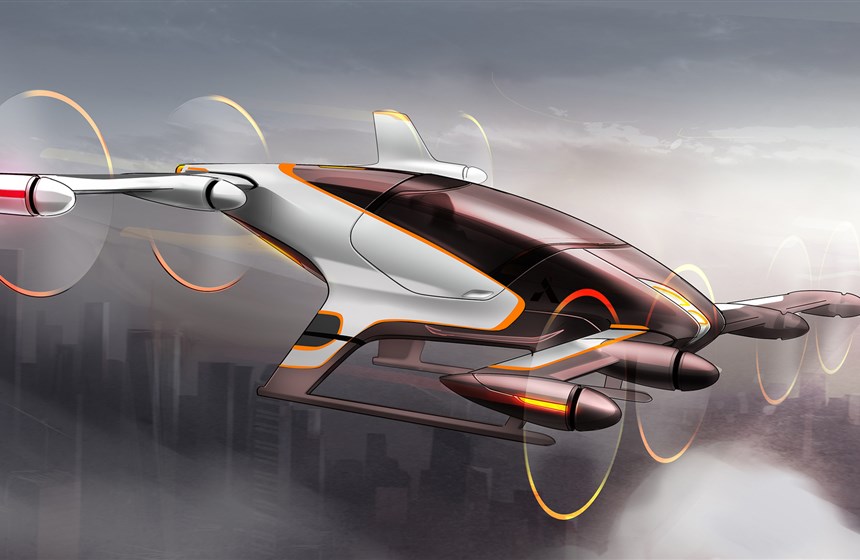

Airbus is developing an autonomous air taxi dubbed Vahana. The tilt-wing, multi-propeller craft is designed to take off and land in tight spaces and able to fly about 50 miles before its batteries need recharging.

Vahana is intended for short urban hops — but what about long flights? How far away are we from a pilotless airliner?

Airbus’s main rival, Boeing, has hinted that such a craft might be on the way. At the Paris Air Show last summer, Mike Sinnett, the company’s vice-president of product development, said “the basic building blocks of the technology clearly are available.” Key elements, including the artificial intelligence system “that makes decisions that pilots would make,” will be tested next year.

Even before truly pilotless airliners show up, we may see a reduction in cockpit crew numbers.

SHRINKING COCKPIT CREWS

“What the industry is telling me is that they would like to remove one of the pilots fairly soon, and re-design the cockpit around a single pilot,” says Stephen Rice, a professor at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Florida. That would involve at least a modest cockpit redesign, so that a single pilot is able to operate all of the controls. “There might also be a remote-control pilot on the ground, in case of emergencies, like a heart attack,” he adds. “This remote pilot could monitor many airplanes [at once].” But eventually “they would like to remove the last pilot.”

This wouldn’t be the first time the aviation industry has cut back on crews. In the 1950s, it took five people to fly an airliner — two pilots, a flight engineer, a radio operator, and a navigator. By the 1960s, the radio operator and navigator were gone. In the 1990s, flight engineers disappeared. Given this trend, fully automated aviation may seem inevitable.

One motive for the trend, not surprisingly, is financial. A report released last August suggests that by transitioning to self-flying aircraft the aviation industry could save $35 billion a year.

Whether air travelers are ready to board a pilotless plane is another matter. The same report found that only one in six passengers would feel comfortable in a fully automated plane.

Of course, passengers may not realize just how much a pilot’s job has already been automated. “On an average flight, the pilots manually control the plane for about three to six minutes, and the rest is autopiloted,” says Rice. He says some airlines don’t let their pilots fly manually once the plane has reached cruising altitude “because they understand that the autopilot is actually safer.”

Which brings up another consideration in the move toward pilotless airliners: safety.

AVERTING AIR DISASTERS

By almost any measure, commercial aviation is one of the safest modes of transportation. More than 30,000 die in the U.S. each year in car crashes. The number of people killed in airliner crashes rarely exceeds 50 a year, and in many years it’s zero. And in those rare cases when something goes wrong, pilot error is often the cause. Pilotless flight could make aviation accidents even more of a rarity.

Consider three recent crashes. In 2013, a UPS cargo jet crashed in Alabama, killing both pilots; an investigation blamed the crash on fatigue and pilot error. The following year, a Malaysian Airlines flight strayed off course and vanished; though the cause of the presumed crash remains a mystery, the jet is believed to have plunged into the Indian Ocean. In 2015, a Germanwings plane crashed in the Alps, killing all 150 people on board; later it was determined that the pilot was mentally disturbed and had crashed on purpose.

Improved automation might have averted at least some of these disasters — for example, by making it harder for pilots to override autopilot system. A plane could be programmed to reject a course change that would take it too far from land, for example, or a change-of-altitude command if it would direct the plane below the height of surrounding terrain.

“You’re looking at very simple calculations,” says Ella Atkins, a professor of aerospace engineering at the University of Michigan. Automated systems can crunch the numbers and determine if, for example, a plane is flying dangerously low — “and if the answer is yes, then the automation can and should stop that accident from happening.”

Such “refuse-to-crash” software is already in use. Since 2014, the U.S. Air Force’s F16 fighter jets have used Lockheed Martin’s Automatic Ground Collision Avoidance System, which is credited with saving the lives of four pilots. In the case of the UPS crash, “more advanced refuse-to-crash automation would have prevented the plane from being flown into the ground by a tired flight crew,” says Atkins. “To my knowledge there really wasn’t anything wrong with the plane.”

SAVING THE DAY

Then again, there have been times when pilots have saved the day. When a U.S. Airways flight lost power after striking a flock of geese shortly after takeoff from LaGuardia in 2009, Captain Chesley Sullenberger, a pilot with nearly 30 years of experience, guided the plane to a water landing on the Hudson River. All 155 people on board survived.

“Sully was an awesome pilot, and did the right things,” says Atkins. “That said, the reason he needed to do those things is because that very simple mathematical code was not on that airplane.” Data indicating the plane’s position and speed, as well as the fact that it had lost thrust, could have “triggered the software” to execute a safe runway landing, she says.

And yet the very idea of pilotless airliners raises big questions. How would the Federal Aviation Administration, which regulates civil aviation in the U.S., decide when a pilotless plane is flightworthy? Who — or what — onboard entity would deal with medical emergencies or unruly passengers? And how could we ensure that self-flying planes couldn’t be hacked?

Ultimately, Rice says, self-flying aviation will take off only if the traveling public trusts it. Tests of aircraft might start in remote areas — perhaps Alaska, he suggests — as pilotless technology is gradually phased in. If those trials are accident-free for a number of years, the public may be won over. The technology may further prove itself in the military sphere, and for carrying cargo.

“Human beings don’t like new things,” says Rice. “They’re afraid, and they let that fear make their decisions for them. But if you give them a good safety track record, then they’ll come around.”

by Dan Falk, NBCNews.com