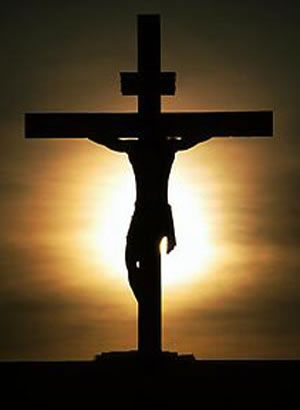

Hundreds of years before Jesus, the Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, said, “I teach only about suffering and the end of suffering.” In Buddhism, the core intent is to end suffering; in Christianity, the core intent is to ennoble it. Jesus didn’t teach that however.

Perhaps because I’m not a Buddhist, but retain, without being a Christian either, some affinity for Jesus’ failed mission and the needlessness of his perceived suffering, I have some insight into the Buddha’s statement.

Perhaps because I’m not a Buddhist, but retain, without being a Christian either, some affinity for Jesus’ failed mission and the needlessness of his perceived suffering, I have some insight into the Buddha’s statement.

Suffering certainly has been at the core of the human condition, but it is not a means to character formation. To ennoble suffering is to condemn our children and future generations to continued suffering. People don’t need to suffer, and children don’t develop into mature adults through suffering.

Having passed through great suffering, the tendency is to believe that the suffering formed us. But it didn’t. Meeting and ending suffering is what forms character.

Mouthpieces for the dead culture extol the virtue of suffering. But to speak about the nobility of suffering when so many people in the world are suffering needlessly is unconscionable. The world is full of immense suffering to be sure, but most of it is utterly unnecessary, the result of self-generated division, conflict and disorder.

We’re not talking about pain, which is often automatically linked in the same breath with suffering, as ‘pain and suffering.’ Young children and animals feel pain, but they don’t suffer. Pain is inevitable; to a point it has to be accepted and met with stoicism, not avoided at all costs. But emotional suffering is generated by human ignorance.

Suffering is a psychological and emotional condition based on the accretion of experience and the continuity of the self. Empty the content of experience, and end the continuity of the self, and there is no suffering. Even if the backwash of the past seeps back in like the tide, ending and emptying the content of the past is vitally important, because doing so provides space for insight, understanding and freedom.

I met a man once who had been arrested during the dark days in Argentina, when many young people were torture, killed or disappeared. He was thrown into a small cell alone, in a long cellblock filled with his compatriots, some of them his friends.

One night the torture began. They started at one end of the cellblock and worked their way toward him, one screaming prisoner at a time. He was, needless to say, going out of his mind as the terror approached. The torturers were quick, methodical and merciless. Each prisoner was subjected to  unseen and unspeakable pain over less than an hour.

unseen and unspeakable pain over less than an hour.

As the screams of torture and a black dawn drew near, he felt on the edge of madness. A voice came to him, calm and clear: “They are torturing you twice.” Decades later, he still didn’t know where it came from. It doesn’t matter. He instantly saw the truth of it and became very calm.

When the door to his cell opened, and an officer and two brutes stood before him, he looked them in the face without fear. The man in charge said, “Do you know what we’re going to do to you?” He responded, “You’re going to do what you’re going to do.”

“Aren’t you afraid?” Instead of answering, this ordinary turned extraordinary young fellow asked a question in return: “Why are you doing this?” They closed the door and walked away. He was released the next day.

Torture is really about the suffering of the torturers. When Americans became torturers, and worse, when we contracted out torture to other countries under the Bush-Cheney Administration, we proved that we had become a weak people who needed to make others suffer, allegedly to save us from the fear and insecurity of terrorism. But we only suffered more.

If suffering were a good teacher, then humankind would be very wise by now. Suffering has been the core trait of the human condition since the beginning of civilization, if not the beginning of man. But we have learned nothing from it, except for the rare individual who looks deeply within when they suffer. Besides, behind the veneer of happiness, suffering is growing.

Holiness comes through the understanding of the roots of suffering, in oneself and others. But holiness, like understanding, only grows through negation, not through any kind of positive action. It has little to do with churches and nothing to do with religious institutions. Irrespective of language, culture and religion, holiness is a quality that flows into and through self-knowing human beings who know how to observe the mind into silence.

Whatever word one wants to give for the actuality that produces genuine awe, wonder and reverence—the nameless, the Brahman, God—it is not a function of science and knowledge. Holiness is not predictive.

The human mind that has uncovered the secrets of nature, developed knowledge and created everything in the built and technological world has nothing to do with holiness. In the final analysis, and beyond analysis altogether, prediction is a paltry thing.

Evil can speak of holiness, therefore one has to be very skeptical, trusting only what one is directly experiencing, and doubting even that. If one knows how to observe without the observer, one knows how to end suffering within oneself.

Martin LeFevre