Yesterday was windy, and the strong breezes burnished the foothills, making the sentinel rock in the canyon stand out sharply against a cobalt blue sky. The winds calmed down by midnight, and before going to bed I went out to look at the stars, as I usually do when it’s clear here (which is nearly every night during the summer). The Milky Way was as clear as I’ve ever seen it in town.

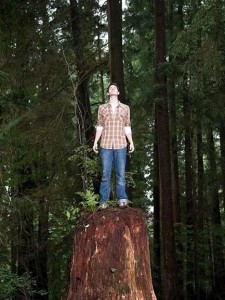

I stood on the stump of the tree they had to cut down after a previous windstorm two weeks ago. It had split down the middle, falling across the fence in back, amazingly causing very little damage. Having watched a show about the Milky Way that night, observation, knowledge, and imagination combined to produce a powerful sensation of wonder and movement in an infinite sea of stars.

I stood on the stump of the tree they had to cut down after a previous windstorm two weeks ago. It had split down the middle, falling across the fence in back, amazingly causing very little damage. Having watched a show about the Milky Way that night, observation, knowledge, and imagination combined to produce a powerful sensation of wonder and movement in an infinite sea of stars.

There was an overwhelming feeling, standing on that stump, of being on a small rock in space. I literally felt dizzy and had to step off the stump onto the ground. It was one of the most intense experiences of the universe in my life, and showed me how direct perception can be enhanced by knowledge and imagination. But they have to be in that order, since imagination without knowledge can easily become delusion, and knowledge without silent perception inevitably becomes hubris.

There are about 200 billion stars in our galaxy alone, and there are probably hundreds of billions of galaxies in the universe. Even with the Hubble telescope, astronomers have only been able to observe about 3000 galaxies. And only a few, such as Andromeda (which will collide with the Milky Way in a few billion years) are visible with the naked eye.

The Earth revolves around an ordinary star on one side of the fairly flat disc that is the Milky Way, so what we’re seeing when we observe what the Greeks called the ‘milky circle’ is millions of stars looking across to the other side. Almost all of the great ancient astronomers of Greece, including Hipparchus and Thales (with the exception of Aristarchus) believed, like Aristotle, that the sun and planets revolved around the earth.

The ancient Greeks weren’t being anthropocentric, but came to their conclusion that the sun went around the earth because they couldn’t detect parallax, the effect whereby the position of an object appears to differ when viewed from different positions.

Using geometry and logic rather than direct observation, since they had no telescopes, the ancient Greek astronomers realized that if Aristarchus was right, and the earth went around the sun, then the earth was also moving relative to the stars. But they couldn’t believe that stars could be trillions of miles away, which makes parallax indiscernible to the naked eye.

So until Galileo, using the first telescopes a thousand years later, was able to detect minute angles of difference relative to the changing position of the earth as it revolved around the sun, everyone believed the earth was at the immovable center of the universe. And if he hadn’t recanted (muttering under his breath, “and yet it moves”), the Roman Catholic Church would have burned Galileo at the stake for his discoveries.

to the changing position of the earth as it revolved around the sun, everyone believed the earth was at the immovable center of the universe. And if he hadn’t recanted (muttering under his breath, “and yet it moves”), the Roman Catholic Church would have burned Galileo at the stake for his discoveries.

At a time when humankind is facing unprecedented challenges, and the world is undergoing unparalleled change, upholding the primacy of any faith, even with a velvet glove, feeds global conflict. Catholicism, which is supposedly synonymous with universalism, has a greasy history of giving lip service to cherishing the whole of the human race, while actually viewing other faiths as “gravely deficient.”

That was according to Joseph Ratzinger in 2000. He was the intellectual anchor of the Catholic Church and alter ego of Pope John Paul during a time when the church was mute during the genocide in Rwanda, and when its priesthood was forever stained with cover-ups of pedophilia in America and Europe.

Ratzinger had often been described as the power behind the throne, the purifier of the church’s doctrine. One can only  deduce that in him the world got exactly what the instantly canonized John Paul wanted. Benedict decries “the dictatorship of relativism,” but exalts in the decrepitude of dogmatism.

deduce that in him the world got exactly what the instantly canonized John Paul wanted. Benedict decries “the dictatorship of relativism,” but exalts in the decrepitude of dogmatism.

The issues go far beyond the Catholic Church, and its billion-plus practicing or nominal members. In a chaotic, colliding world where the old faiths and forms have become extraneous and irrelevant, everyone is faced with what it means to be a good human being. Can organized religions only get in the way of the awakening of the human mind?

The new pope, who many scholars think has been trying to position himself as the savior of Europe, believes that Christ (the theological image of Jesus) is the only way. Benedict decries and dismisses what he calls “vague religious mysticism,” which is actually the wellspring of spirituality.

It all boils down to one’s orientation to truth (including whether one even feels there is such a thing). Truth is a living movement that emerges with the spontaneous stillness of the mind. Truth therefore cannot and does not lie in any doctrine or dogma, and is indiscernible to people who are anchored in texts and traditions rather than in the insight that comes from self-knowing.

The truth is neither relative, nor a doctrine that can be written down and codified for two thousand years. Because the truth cannot be captured and contained does not mean it doesn’t exist, and everything is subjective.

To understand what Jesus, or any other true religious teacher is talking about, one has to inwardly negate everything in silent awareness, including what he and other teachers have said. One has to feel, as Socrates said, “I know one thing, that I know nothing,”

Again, that doesn’t mean everything is personally subjective. Asserting a nonexistent objective truth, or indulging in pure subjectivism are actually two sides of the same coin.

The truth is not ‘somewhere in between.’ It’s not on any silly scale at all. It’s there for a moment stumbling on a stump, and then gone on the breeze.

Martin LeFevre