A palpable pall hung over the land yesterday, the 4th of July, the day America celebrates its birth as a nation. Ostensibly from uncontained wildfires in the region, the pallor seemed disturbingly fitting this Fourth.

Though I had an excellent day, spending most of it in the beautiful canyon just beyond town, meditating, hiking, swimming and meeting and talking with new people, the zeitgeist was a somber and sad Independence Day.

The national darkness that gave rise to Trump, and is being catalyzed by him, is emotionally affecting everyone in America. People are keeping up a good face, but there’s a widespread feeling that America is sinking into the muck.

What little cable news I watched yesterday featured a tortured analysis showing our paralysis, as pundits parsed the ‘nuanced’ distinction between nationalism and patriotism. In actuality, the morphing of tribalism, nationalism, patriotism and xenophobia is now complete in the USA.

In a gift to philosophers everywhere, Megan McArdle boneheadedly wrote in the Washington Post:

“Nationalism” has become a dirty word in the modern era, having become inextricably associated with repression of minorities and imperialist ambition. We’ve forgotten that the nationalists actually did start out in the 19th century with a worthy and difficult project: persuading a large group of people to think of themselves as a single unit.”

It’s astounding that such claptrap is given space in one of America’s leading newspapers. In an irrefutably global society, why is it necessary to point out that “persuading a large group of people to think of themselves as a single unit” is now the project of human beings everywhere?

It’s astounding that such claptrap is given space in one of America’s leading newspapers. In an irrefutably global society, why is it necessary to point out that “persuading a large group of people to think of themselves as a single unit” is now the project of human beings everywhere?

One cannot both see oneself first as a human being and see oneself first as an American or any other fragment of humanity.

It is utterly fallacious to argue, reductio ad absurdum, “We may debate whether the U.S. government should provide health care for all its citizens, but we are not arguing about whether we should open up an Obamacare exchange in Chad.”

“Claims about obligations to fellow Americans would be nonsensical without an important, and binding, national identity,” McArdle pronounces.

A first year undergraduate student could spot that non sequitur from her dorm room. Which is ironic because McArdle argues, in a stunning revelation of her own inanity, “We evolved in the African plains, not a freshman philosophy seminar.”

What does that even mean—except upholding egregious, outdated ideas about the nature of human nature?

McArdle wades into deep water with a child’s doughnut, keeping herself afloat by proclaiming that “our particular species is groupish,” adding “most of us do not want to think of the place we live as merely another sort of consumer choice, and of our neighbors as nothing more than fellow consumers.”

Since it is precisely consumerism that has erased and effaced the former differences of place, except the touristic veneer of prior traditions, and since consumers is precisely the way that people are viewed and largely view each other in corporate global America, that argument takes the cake for naïveté and unintended irony.

McArdle is not without insight, as when she says, “The groupish instinct has not gone away, and neither has it leveled up into a mass identification with all humanity. Instead, it has leveled down, into a global outbreak of populist particularism.”

But in the next breath she prescribes more of the disease for a cure: “If we are to fight our way back from this soft civil war, we will need a muscular patriotism that focuses us on our commonalities instead of our differences…we desperately need the flag, and the anthem, and all the other common symbols.”

What would that “muscular patriotism” look like, Megan? Perhaps a world war?

Like so many Americans (epitomized by a president who says one thing in the morning and the opposite that night) McArdle sees no reason she can’t have it both ways.

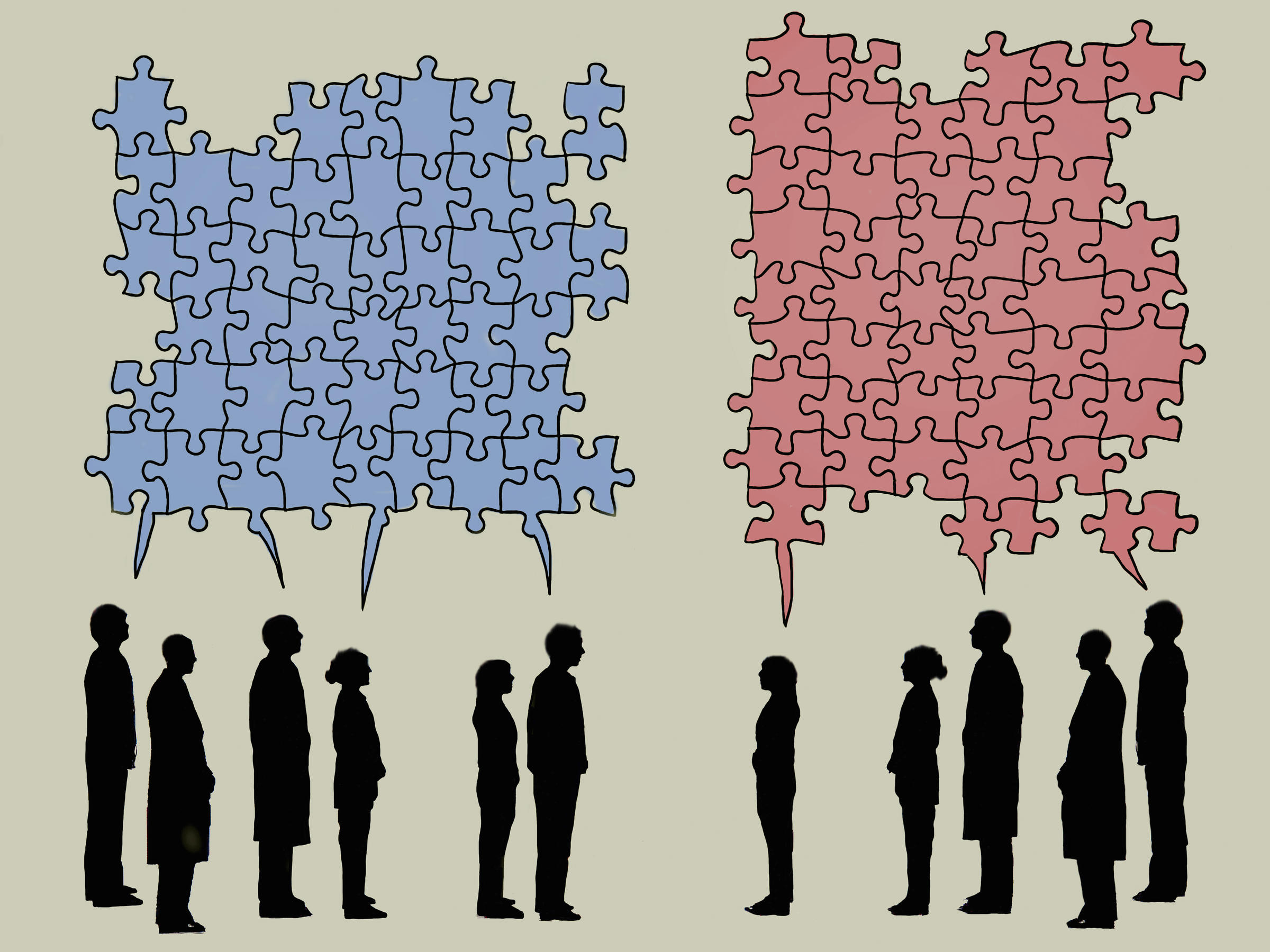

“Particularism is threatening to tear the United States apart as rival tribes lose the ability to do anything together.”

No, particularism, which is just another form of tribalism, broke down into its sub-nationalistic divisions after the last gasp of nationalistic identification following 9.11.

Seeing oneself first as a human being is congruent with being a good citizen of America or any nation. However seeing oneself first as an American or a Russian, as an Iranian or Saudi Arabian, precludes one from being a good human being.

Indeed, given our undeniably interconnected world economy and society, no matter how much an atavistic Trump is working to take us back to 19th century through a trade war with China (and even Canada for humanity’s sake), being a good global citizen has become necessary precondition to being a good American citizen.

Listen and take to heart: To be a good American, or citizen of any country, it has become essential to see oneself first as a human being.

Martin LeFevre