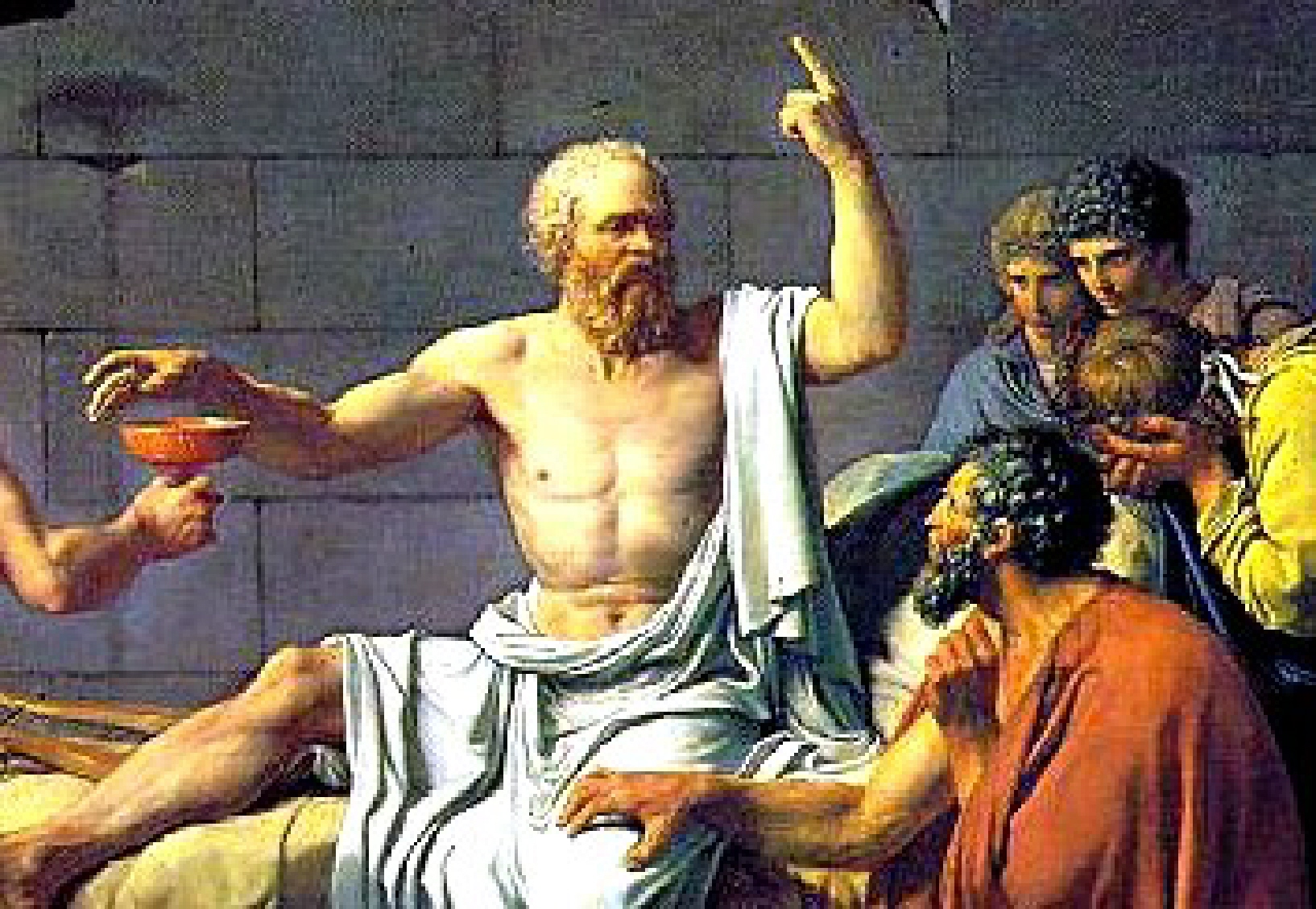

It’s a mystery how the essence of a person, even one who lived 2500 years ago, can be conveyed through the written word. Especially when that person, Socrates, decried the written word.

Facing a death sentence at the end of his trial, Socrates, as told by Plato in the Apology, spoke these final words to the large jury of his peers in Athens: “When my sons grow up, avenge yourselves by causing them the same kind of grief that I caused you, if you think they care for money or anything else more than they care for virtue, or if you think they are somebody when they are nobody.” That didn’t go over so well.

Facing a death sentence at the end of his trial, Socrates, as told by Plato in the Apology, spoke these final words to the large jury of his peers in Athens: “When my sons grow up, avenge yourselves by causing them the same kind of grief that I caused you, if you think they care for money or anything else more than they care for virtue, or if you think they are somebody when they are nobody.” That didn’t go over so well.

As G.M.A. Grube says in his translation of the Apology, “the beauty of language and style is certainly Plato’s, but the serene spiritual and moral beauty of character belongs to Socrates. It is a powerful combination.”

The trial, by 501 Athenian citizens, took place in 399 BC, and Socrates was convicted on charges of corrupting the youth and impiety. What that actually meant was that Socrates had to be gotten rid of, since he was discrediting the older generation’s views and reputations through his relentless questioning.

Plato’s “Apology” is fascinating reading, but ‘apology’ a misleading transliteration, since the word in Greek is actually apologia, which means defense or justification. What interests me here however, are not the circumstances of Socrates death, but his views on writing.

Socrates and Plato lived during a time of transition between the oral and written traditions. For uncounted generations, knowledge and culture had been transmitted more by ear than by sight.

As one scholar put it, “a strictly oral culture seemed to require externalization of reflections, and the technology of writing gave humanity an increased capacity for leisured internalization and introspection.”

Socrates realized this was a profound shift, and he distrusted it. The arguments that he makes against writing through Plato, a generation his junior, are echoed in concerns people have against the Net and electronic communications. Mainly they are that it diminishes memory, and reduces presence on the human level.

Socrates method of teaching was through direct discourse, challenging the individual by questioning his (it was a male-dominated society) core assumptions and premises.

Though I don’t subscribe to his dialectical method, I do feel continually questioning core assumptions and premises is what a philosopher does, or should do. The truth is revealed through negation, not through assertion.

Plato went so far as to say that Socrates was the god’s gift to the Athenians. Yes, and they killed him.  American culture has evolved much further; it just ignores people who speak the truth, until they quit, conform and/or are broken.

American culture has evolved much further; it just ignores people who speak the truth, until they quit, conform and/or are broken.

With regard to writing, Socrates said in Phaedrus, “…writing is unfortunately like painting; for the creations of the painter have the attitude of life, and yet if you ask them a question they preserve a solemn silence.” But is that false?

Most philosophers believe that the argument has been won in favor of writing. Some thinkers go so far as to say, “Writing has restructured human consciousness in a way that has increased both wisdom and cultural memory.” That’s balderdash of course.

What would Socrates and Plato think of hand-held devices that give a person access to almost all knowledge and most people on the planet? Wouldn’t they point out that we have substituted data for knowledge, ‘trending now’ for wisdom, and electronic links and blinks for human presence and essence?

“Knowing love or thinking philosophically is something else entirely,” as someone once said.

In my youth, I was of two minds about writing. On one hand, I rarely went a day without writing, if only in my journals. On the other hand, I grew up in a house without books and with an active disdain for intellectuals, whom my father called “smart dummies.”

I sometimes describe writing a column like finding a precious stone, polishing it, and then dropping it into a deep well and walking away. Whether it causes any ripples of truth within the reader is almost always unknown to the writer, and perhaps should remain so.

There was one exception that showed me that writing really could make a difference. I took writing more seriously afterward, and felt a greater responsibility in writing a column.

When I first moved to this town nearly 20 years ago, I was able to get a non-sectarian spiritual and philosophical column in the local conservative paper. After two years, the column had drawn readers across educational, income and ethnic lines. (The paper first censored and then cut ‘Contemplations’ after it ran three years.)

One day, a friend said she had received a message that she had been told to pass onto me. A friend of hers, who I didn’t know, knew a therapist that had a troubled young man as a client. Unbeknownst to the therapist, the young man had decided to commit suicide.

Plans were made to the degree that he reached that state of calm people describe before they do the unalterable deed. He picked up the local paper for some reason that morning, which he said he rarely read, and happened upon my column. The nature description and contemplative piece moved him, a little.

Just enough, he reported, that something in him said ‘wait.’ He drove up into the mountains just outside of town, where he decided to postpone his all-but-final plans to do away with himself. Over the ensuing days, he had a change of heart, and then told his therapist about the whole thing.

“If you have a way to get a message to that writer,” he said, “without him knowing who I am, tell him that that column saved my life.”

I still don’t think writing has changed or can change human consciousness, but touching even one person’s life is something. That would be my response to Socrates.

Martin LeFevre