Though I’m not a Buddhist, Buddhist philosophy and poetry (as opposed to the arcane intricacies of various Buddhist traditions) speak to me. The quieting and emptying of the mind and opening of the heart have become a universal imperative, whether we call it contemplation, prayer or meditation.

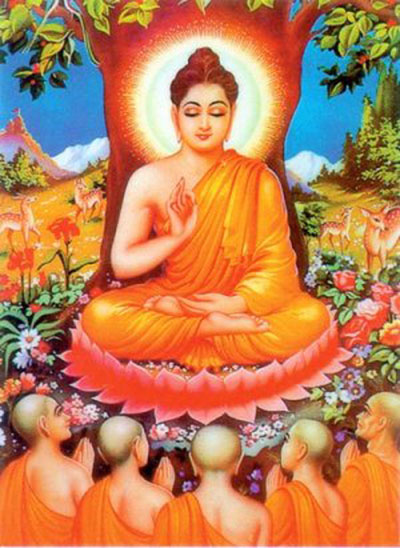

Buddhism has its central figure in Siddhartha Gautama, and Christianity has its central figure in Jesus of Nazareth. However the similarities, at least as far as the religions, ends there. Indeed, Buddhism doesn’t even think of itself as a religion.

Buddhism has its central figure in Siddhartha Gautama, and Christianity has its central figure in Jesus of Nazareth. However the similarities, at least as far as the religions, ends there. Indeed, Buddhism doesn’t even think of itself as a religion.

Essentially, Buddhism has been a philosophy of interiority, whereas Christianity has, for the most part, been a belief system of exteriority. One is compelled to ask: Which orientation would Jesus counsel?

Clearly, he taught the path of interiority, despite the externalizing distortions of Christianity. Now that the way of exteriority has come to its logical end, a true dialogue between those who feel an affinity for the historical Jesus, and pupils of the unencumbered-by-tradition Siddhartha becomes vital.

Given that Christianity is a religion of positive action, while Buddhism is philosophy of negation, what part does a relationship with nature play in both?

The story of Jesus’ trial in the desert consciously and subconsciously associates nature with pitiless wilderness. It’s no coincidence that Christian theology places Jesus’ encounters with Satan in the desert, but completely neglects his demise at the hands of darkness in Jerusalem.

(After his death, Jesus’ followers, and especially Paul, invented the story that Jesus was sent and meant to die on the cross all along.)

The Bible records very little Jesus said about nature. The most striking metaphor is this:

“The eye is the lamp of the body. So if your eye is clear, you whole body is luminous; but if your eye isn’t clear, your whole body is dark. And if the light in you is darkness, how great that darkness is.”

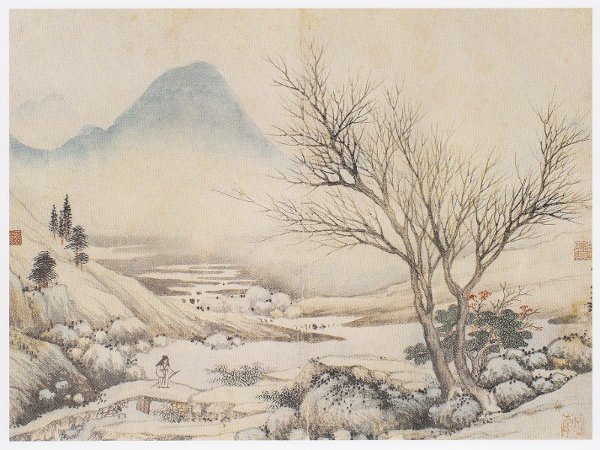

In tone and spirit, this aligns with core Buddhist teaching. For example, there’s this story in “Dropping Ashes on the Buddha,” by Stephen Mitchell, of Su Tung-p’o, an 11th century Chinese poet, painter and civil servant.

“At the Temple of the Ascending Dragon there was a famous Zen Master named Chang Tsung. Su Tung-p’o went to him and said, ‘Please teach me the Buddha-Dharma and open up my ignorant eyes.

The Master, whom he had expected to be the very soul of compassion, began to shout at him. ‘How dare you come here seeking the dead words of men! Why don’t you open your ears to the living words of nature?’

Su Tung-p’o staggered out of the room. What had the Master meant? What was the teaching that nature could give and men couldn’t?

Totally absorbed in his question, he mounted his horse and rode off. He had lost all sense of direction, so he let his horse find the way home. It led him on a path through the mountains.

Suddenly he came upon a waterfall. The sound struck his ears. He understood. So this is what the Master meant! The whole world—and not just this world, but all possible worlds, all the most distant stars, the universe itself—was identical to himself. He got on his horse and bowed deeply, in the direction of the monastery.”

Returning home, Su Tung p’o penned this poem:

The roaring waterfall

is the Buddha’s golden mouth.

The mountains in the distance

are his pure luminous body.

How many thousands of poems

have flowed through me tonight!

And tomorrow I won’t be able

to repeat even one word.

It’s important to understand that the Buddha in this understanding is not identical with Gautama, but that Gautama was apparently identical with the Buddha mind.

In the same way, despite what most Christians believe, Christ is not identical with Jesus, but Jesus was identical with Christ. Even that is open to question however, since the word Christ has a two meanings. Christ is a Greek translation of the Hebrew word for messiah, the savior of the Jews. It also means “the anointed one.”

Clearly, Jesus was an anointed one, as difficult as it is for us accept the notion of anointing in our secular, scientific age. But Jesus didn’t fulfill his role as messiah, since he didn’t save the Jews. His mission failed. Sadly, Jews are still waiting for their messiah.

No one, not even the immanent God, can save people from themselves. The Jews of Jesus’ time didn’t listen, and so he could not save them. Ever since they’ve maintained he wasn’t the messiah after all. That remains a tragic, vicious circle, not only for Jews, but for Christians as well.

Martin LeFevre