WASHINGTON — The Senate, in a predawn vote two hours after the deadline passed to avert automatic tax increases, overwhelmingly approved legislation on Tuesday that would allow tax rates to rise only on affluent Americans while temporarily suspending sweeping, across-the-board spending cuts.

The deal, worked out in furious negotiations between Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. and the Republican Senate leader, Mitch McConnell, passed 89 to 8, with just three Democrats and five Republicans voting no. Although it lost the support of some of the Senate’s most conservative members, the broad coalition that pushed the accord across the finish line could portend swift House passage as early as New Year’s Day.

The deal, worked out in furious negotiations between Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. and the Republican Senate leader, Mitch McConnell, passed 89 to 8, with just three Democrats and five Republicans voting no. Although it lost the support of some of the Senate’s most conservative members, the broad coalition that pushed the accord across the finish line could portend swift House passage as early as New Year’s Day.

Quick passage before the markets reopen on Wednesday would be likely to negate any economic damage from Tuesday’s breach of the “fiscal cliff” and largely spare the nation’s economy from the one-two punch of large tax increases and across-the-board military and domestic spending cuts in the New Year.

“This shouldn’t be the model for how to do things around here,” Mr. McConnell said just after 1:30 a.m. “But I think we can say we’ve done some good for the country.”

Mr. Biden, after a late New Year’s Eve meeting with leery Senate Democrats to sell the accord, said: “You surely shouldn’t predict how the House is going to vote. But I feel very, very good.”

The eight senators who voted no included Marco Rubio, Republican of Florida and a potential presidential candidate in 2016, two of the Senate’s most ardent small-government Republicans, Rand Paul of Kentucky and Mike Lee of Utah, and Senator Charles E. Grassley of Iowa, who as a former Finance Committee chairman helped secure passage of the Bush-era tax cuts, then opposed making almost all of them permanent on Tuesday. Two moderate Democrats, Thomas R. Carper of Delaware and Michael Bennet of Colorado, also voted no, as did the liberal Democrat Tom Harkin, who said the White House had given away too much in the compromise. Senator Richard C. Shelby, Republican of Alabama, also voted no.

The House Speaker, John A. Boehner, and the Republican House leadership said the House would “honor its commitment to consider the Senate agreement.” But, they added, “decisions about whether the House will seek to accept or promptly amend the measure will not be made until House members — and the American people — have been able to review the legislation.”

Even with that cautious assessment, Republican House aides said a vote Tuesday was possible.

Under the agreement, tax rates would jump to 39.6 percent from 35 percent for individual incomes over $400,000 and couples over $450,000, while tax deductions and credits would start phasing out on incomes as low as $250,000, a clear victory for President Obama, who ran for re-election vowing to impose taxes on the wealthy.

Just after the vote, Mr. Obama called for quick House passage of the legislation.

“While neither Democrats nor Republicans got everything they wanted, this agreement is the right thing to do for our country and the House should pass it without delay,” he said.

Democrats also secured a full year’s extension of unemployment insurance without strings attached and without offsetting spending cuts, a $30 billion cost. But the two-percentage point cut to the payroll tax that the president secured in late 2010 lapsed at midnight and will not be renewed.

offsetting spending cuts, a $30 billion cost. But the two-percentage point cut to the payroll tax that the president secured in late 2010 lapsed at midnight and will not be renewed.

In one final piece of the puzzle, negotiators agreed to put off $110 billion in across-the-board cuts to military and domestic programs for two months while broader deficit-reduction talks continue. Those cuts begin to go into force on Wednesday, and that deadline, too, might be missed before Congress approves the legislation.

To secure votes, Senator Harry Reid, the Senate Democratic leader, also told Democrats the legislation would cancel a pending Congressional pay raise — putting opponents in the politically difficult position of supporting a raise — and extend an expiring dairy policy that would have seen the price of milk double in some parts of the country.

The nature of the deal ensured that the running war between the White House and Congressional Republicans on spending and taxes would continue at least until the spring. Treasury Secretary Timothy F. Geithner formally notified Congress that the government reached its statutory borrowing limit on New Year’s Eve. Through some creative accounting tricks, the Treasury Department can put off action for perhaps two months, but Congress must act to keep the government from defaulting just when the “pause” on pending cuts is up. Then in late March, a law financing the government expires.

And the new deal does nothing to address the big issues that Mr. Obama and Mr. Boehner hoped to deal with in their failed “grand bargain” talks two weeks ago: booming entitlement spending and a tax code so complex that few defend it anymore.

Though the deal ultimately passed the Senate, it was greeted with skepticism on Capitol Hill when it was first outlined on Monday. Republicans accused the White House of “moving the goal posts” by demanding still more tax increases to help shut off across-the-board spending cuts beyond the two-month pause. Democrats were incredulous that the president had ultimately agreed to around $600 billion in new tax revenue over 10 years when even Mr. Boehner had promised $800 billion. But the White House said it had also won concessions on unemployment insurance and the inheritance tax among other wins.

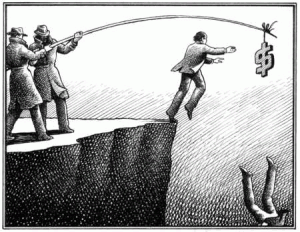

Still, Democrats openly worried that if Mr. Obama could not drive a harder bargain when he holds most of the cards, he will give up still more Democratic priorities in the coming weeks, when hard deadlines will raise the prospects of a government default first, then a government shutdown. In both instances, conservative Republicans are more willing to breach the deadlines than in this case, when conservatives cringed at the prospects of huge tax increases.

“I just don’t think Obama’s negotiated very well,” said Senator Tom Harkin, Democrat of Iowa.

With the legislation now headed to the House, Republicans there signaled that enough of them, in combination with Democrats, could most likely pass the legislation, just weeks after Republicans shot down Mr. Boehner’s proposal to raise taxes only on incomes over $1 million.

“I don’t want to say where I am until I read the legislation, but it is certainly better than the alternative,” said Representative Charlie Dent, Republican of Pennsylvania.

With the threat of huge cuts agonizingly close, official Washington was prepared for the worst. The Defense Department prepared to notify all 800,000 of its civilian employees that some of them could be forced into unpaid leave without a deal on military cuts. The Internal Revenue Service issued guidance to employers to increase withholding from paychecks beginning Tuesday to match new tax rates at every income level.

“No deal is the worse deal,” said Senator Joseph I. Lieberman, independent of Connecticut, rejecting the assertions of liberal colleagues that no deal would be better than what they would see as a bad deal.

Despite grumbling among Republicans and Democrats, it was clear that a deal hashed out through intense talks between Mr. Biden and Mr. McConnell had given both sides provisions to cheer and to jeer.

Under the deal, tax rates on dividends and capital gains would also rise, to 20 percent from 15 percent, on income over $400,000 for single people and $450,000 for couples. The deal would reinstate provisions to tax law, ended by the Bush tax cuts of 2001, that phase out personal exemptions and deductions for the affluent. Those phaseouts, under the agreement, would begin at $250,000 for single people and $300,000 for couples.

The estate tax would also rise, but considerably less than Democrats had wanted. The value of estates over $5 million would be taxed at 40 percent, up from 35 percent. Democrats had wanted a 45 percent rate on inheritances over $3.5 million.

Under the deal, the new rates on income, investment and inheritances would be permanent, as would a provision to stop the alternative minimum tax from hitting middle-class families.

Jennifer Steinhauer and Robert Pear contributed reporting from The New York Times