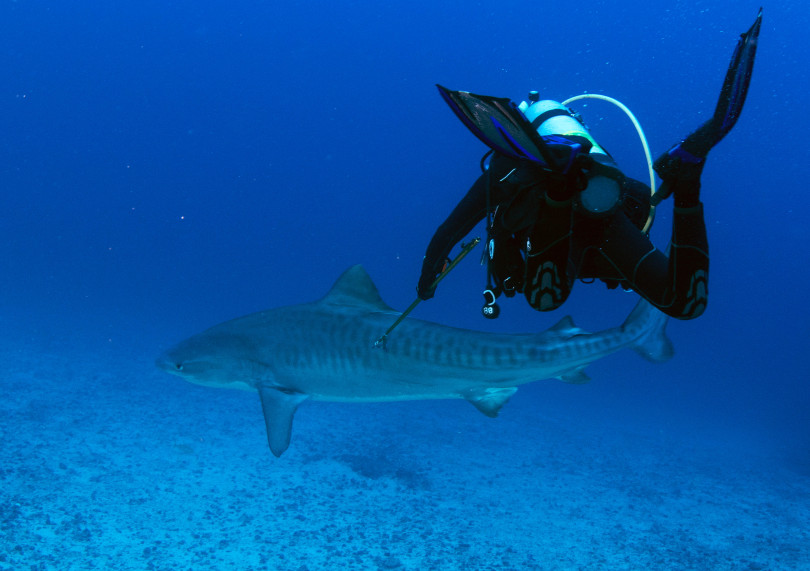

The 14-foot tiger shark began circling Todd Steiner and the team of divers in the waters off Costa Rica — a sign of aggressive behavior from a marine predator that was already suspected of killing an American diver in 2017.

Swimming just feet away from the shark, Steiner thrust a 6-foot pole at the shark’s scarred dorsal fin to implant an acoustic transmitter. The transmitter will be be used to track the shark’s movements and hopefully protect future divers in the tropical waters he and thousands of other divers have come to cherish.

“You’re working on adrenaline at that point,” said Steiner, the executive director of the Olema-based Turtle Island Restoration Network. “By the same token, it was important to get that data so I was driven by the need to protect Cocos Island and to actually protect this animal in the long run. Because if we determine it is not the same animal (that killed the diver) it will allow the park to understand and come up with a conservation strategy.”

Partnering with Costa Rica’s national parks system and citizen scientists, Steiner traveled to the remote Cocos Island National Park more than 300 miles off the coast of Costa Rica from Dec. 7 to 17 to tag the tiger shark along with other shark species and sea turtles. The expedition was continuing their research into a marine life highway between Cocos Island and the Galapagos Islands with the hopes of setting up a 240,000-square-mile marine protected area, known as the Cocos-Galapagos Swimway. Steiner said the Ecuadorian and Costa Rican governments are already in discussions to potentially create this preserve.

But there was also Lagertha, which is the nickname given to the female tiger shark that is suspected to have bitten American tourist Rohina Bhandari, 49, and her dive instructor at the national park in November 2017 while they were surfacing from a dive. The dive instructor survived the attack, but Bhandari did not. Steiner said tiger shark attacks on scuba divers are rare, but there is always some risk in entering the domain of large marine predators.

The goal of tagging the shark is not to allow authorities to track it and kill it, but to study its movements using sensors placed around Cocos Island and the Galapagos Islands as well as a hydrophone that can track its real-time location. Steiner has been making research trips to Cocos Island for 11 years, partnering with the Costa Rica-based organization, the Rescue Center for Endangered Marine Species, and the Costa Rican government to study its wildlife and several critically endangered species. The tropical waters and abundance of sea life makes it a bucket list destination for divers, Steiner said, with the diving fees supporting the park’s conservation efforts.

By tagging the sharks and knowing their behaviors, researchers will be able to help inform dive schedules and alert divers to avoid certain areas where a known hostile animal may be swimming in.

“We want to keep divers safe and want to keep the habitat protected and safe,” Steiner said.

Steiner said they have no evidence that Lagertha was the exact shark that killed Bhandari, but the scars on its dorsal fin and its observed aggressive behavior around humans make it a prime suspect. This same shark was showing aggressive behavior when Steiner and researchers performed a dive in December 2017, shortly after the attack. They had to abort the dive at one point because of the risk.

An Emmy-award winning documentary filmmaker, Alfredo Barroso, was filming Steiner’s latest expedition for a future documentary and described the shark’s behavior as they approached it about 60 feet underwater.

“It was showing no fear of the divers and was slowly and continuously circling us, closing its eyes, which is often a sign of a possible imminent attack,” Barroso said in a statement. “Todd charged the animal and tagged it from about a foot away, causing the shark to swim off and giving us time to get safely back on our skiff.”

Steiner said it wasn’t until after tagging the shark and surfacing that the frightfulness of the situation set in. Despite the danger, Steiner said he and other researchers find inspiration and exhilaration from working to protect and preserve this region of the world.

“Why I went there and why I’ve been back there 27 times was because when I jumped in the water I felt like I was looking at the oceans the way we were before we had industrial fishing that has basically wiped out so much of underwater life,” Steiner said. “It was like looking back in time.”

Steiner said they are looking for experienced, adventurous divers to help participate in future citizen research in the Cocos Island National Park.

By WILL HOUSTON, Marin County Journal