A distinction is commonly made between “the historical Jesus” and the Christ of Christian belief. That’s valid from a historian’s point of view, but as Christianity and all organized religions become increasingly irrelevant, is there a third possibility—the mystic’s Jesus? And is he any more relevant?

Even if one could give such an insight into the man and his mission, what relevance could the son of a carpenter living in a backwater of the Roman Empire have for us today? Besides, there’s so much fiction and outright fraud in Christian history that it may be an exercise in futility to try to resurrect any true insight into who Jesus actually was. But if we want to understand how we came to this pass, there’s something to be said in understanding the central figure in Western history.

Even if one could give such an insight into the man and his mission, what relevance could the son of a carpenter living in a backwater of the Roman Empire have for us today? Besides, there’s so much fiction and outright fraud in Christian history that it may be an exercise in futility to try to resurrect any true insight into who Jesus actually was. But if we want to understand how we came to this pass, there’s something to be said in understanding the central figure in Western history.

As Thomas Jefferson said, “In the New Testament there is internal evidence that parts of it have proceeded from an extraordinary man; and that other parts are of the fabric of very inferior minds. It is as easy separate those parts, as to pick out diamonds from dunghills.”

And if that’s true for the author of America’s Declaration of Independence and the quintessential intellectual (ironically, since Americans hold intellectuals in such disdain), then how much more true is it of a contemplative, who may have direct insight into Jesus’ nature and mission?

In “The Outline of History,” H.G. Wells, said, “Just as the personality of Gautama Buddha has been distorted and obscured by the stiff squatting figure, the gilded idol of later Buddhism, so one feels that the lean and strenuous personality of Jesus is much wronged by the unreality and conventionality that a mistaken reverence has imposed upon his figure.”

I read today about a devout Swedish Christian pastor (a contradiction in terms to some, but there it is), who, after making an exhaustive study of Jesus’ death, declared that Jesus was not crucified and did not die on the cross.

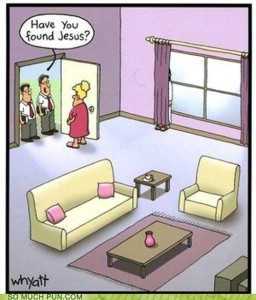

When I spotted the headline I thought, this sounds interesting, but it turned out to be one of those ‘how many angels can dance on the head of a pin’ news stories. The pastor wasn’t challenging any beliefs about Jesus, just whether he was “suspended” from a post, or crucified on the Christianity’s iconic cross.

“I’m just another boring pastor. I think Jesus is the son of God,” proclaimed Gunnar Samuelsson. It’s noteworthy that the automatic spell-check is telling me to capitalize son, as if ‘Son of God’ is a given. It isn’t. That’s is the whole point of this piece.

After some comments I made about Jesus in a recent column, a friend wrote to ask, “Do you believe that Jesus’ mission was a spectacular failure in how he died, given the spread of Christianity throughout the world? Or did you mean that he himself perceived it as failure in his moment of despair?”

There are three questions here, not just two. The first cuts to the core of Christian belief: Was Jesus’ mission a  spectacular failure because of how he died?

spectacular failure because of how he died?

The fundamental mistake (original sin, if you will) of Christianity was the premise, which hardened into an assumption and test of belief over the centuries, that Jesus was meant to ‘die on the cross for our sins.’

If that’s true, and Jesus had been preparing for martyrdom from the beginning, why did he sweat blood (a condition produced by capillaries breaking under extreme stress) in the Garden of Gethsemane the night the Roman soldiers came to take him? (His fate sealed, he thereafter displayed tremendous equanimity before the colluding Jewish and Roman leaders.)

Jesus wasn’t meant to die, but teach and reach people. His guilt-ridden disciples, and the reprobate Paul decades later, invented a narrative that assuaged their guilt, gave rise to a wave of martyrs that the Taliban would envy, and poured the foundation in blood for the Roman Catholic Church.

More directly, there is this completely unheeded injunction from Jesus in Matthew: “Then he charged his disciples that they should tell no man that he was Jesus the Christ.”

The second question pierces to the heart of any mystic/contemplative: Did Jesus himself perceive his mission as a failure in his moment of despair? Of course he did. It was a failure; can we not forgive him a moment of despair?

If his words on the cross (or post) are to be believed, they reflect forth to us like one of those proverbial diamonds in the dunghill. As Wells wrote, “Toward the end of the long day of suffering [portrayed pornographically in Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of Christ’] this abandoned leader roused himself to one supreme effort, cried out with a loud voice, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” and—leaving those words to echo down the ages, a perpetual riddle to the faithful—died.”

Can the riddle be resolved? It can if one looks beyond the metaphor of ‘God the Father,’ and places Jesus in the context of the intent of cosmic intelligence for the transmutation of sentient, potentially sapient creatures such as man.

However divinely inspired and infused with insight and compassion Jesus was, he was a human being and teacher, rather than the singular “Son of God” most Christians believe. People do disservice to Jesus, humanity and themselves by clinging to that belief.

Jesus didn’t fail, but his mission did. The cosmic intent remains, but there is no ‘Messiah,’ only us. In our evolutionary terminology, can the transmutation of man ignite now, at the moment of man’s greatest plundering of the earth, and humanity’s greatest peril of the spirit?

Martin LeFevre