A flock of small birds lands in the shallows, and a few begin furiously beating their wings in the water. More join in, and suddenly there are a dozen birds taking a bath at the same time.

They all seem to be great friends, thoroughly enjoying the late-afternoon splash. One by one they dart off, flying downstream even as others fly up. It is a marvelous sight, full of movement and life.

They all seem to be great friends, thoroughly enjoying the late-afternoon splash. One by one they dart off, flying downstream even as others fly up. It is a marvelous sight, full of movement and life.

Watching everything outside and inside on the mild afternoon, meditation, which is really a spontaneous movement of negation, comes over one like a soft breeze through the trees. Then it deepens into a tremendous gale, completely beyond one’s control, sweeping the mind and heart clean. As always, a meditative state comes unbidden and unsought, when effort, goal seeking and the observer have dissolved in passive awareness.

One’s particular perspective ends too. Naturally everyone has a different perspective. Culture, family, education, religion and even the climate affect how we see things, which varies from place to place and person to person. In one sense, these varying backgrounds make for variety, and a superficial diversity. But as a rule they generate conditioned differences, division and conflict.

Indeed, where conditioned differences are primary, inevitably division and conflict rule. Some people think conditioned differences are good; most people think they are the unchangeable basis of being human. But clearly it’s possible to hold one’s views lightly, and be open to enquiry and insight.

I wonder, are there really individuals in the sense that we think at all, or is human consciousness a collective phenomenon?

Genuine uniqueness and diversity between people can only be when division and conflict don’t dominate human relations. Since division and conflict are common as dirt, the person ending division and conflict within themselves is the unique individual. People who think they’re different in their separateness are actually dividuals.

Obviously we tend to see things from just our own perspective. That’s because we look out on the world from a center, which is the self. And in an extremely individualistic culture, people see things from no other perspective but their own, which leads to narcissism.

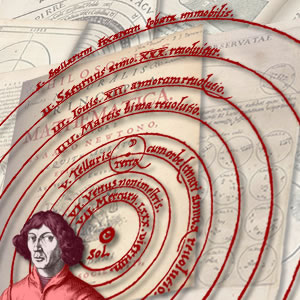

In the first century, the Greek astronomer Ptolemy, working in the great library in Alexandria, produced his earth-centered system of the universe. The Ptolemaic world-view held sway until the 16th century, when Copernicus demonstrated that the Earth revolved around the sun. Einstein in turn overthrew that paradigm, showing that all centers, and even time and space, are relative and in flux, and that no point is fixed in relation to others. There is no center in the universe.

Psychologically however, we cling to a Ptolemaic way of seeing the world, which is producing more and more egocentrism. And since self-centeredness inevitably increases the gaps between people, both politically and economically, this regression in a globalized world is extremely dangerous.

It’s the core reason that rather than ending the worship of war after the bloodiest century in human history, the 20th century, war has become institutionalized as a permanent condition—‘the global war on terror.’ And though humankind now has the scientific and technological means for providing food, clothing, shelter, health care and education to everyone, the gulf between the haves and have-nots is widening nearly everywhere.

The artifice, ‘I’m 50% right, you’re 50% right’ is absurd on the face of it. No one operates with such false modesty. Besides, the truth of things is not an amalgam of different perspectives; it’s an insight in the moment, shared by and with others.

Learning how to look is the key to opening one’s eyes and heart. To look from other people’s perspectives is to see the world through other people’s eyes. That’s certainly a good thing, but even it has limited value when it comes to understanding.

In awakening meditation, one learns how to look from no particular perspective—that is, without a center. Then who or what is looking? There is no separate entity; there doesn’t need to be an observer for observing to take place. In fact, the observer prevents true observation.

When Einstein said, “you can never solve a problem on the level on which it was created,” he was not referring to a ‘creative synthesis’ of separate selves, but to going below and beyond separative and dualistic perspectives, and discovering the unifying principle beneath our contradictions as humans. One can only do so when the observer and center are not operating. That creates the space, listening and newness for insight, which is always new, to be.

In ending the center, does one glimpse the world through God’s eyes? Not in any deistic sense, which is just another thought-projected center, but in the sense of the stillness of seeing at the core of being.

Perhaps, though it’s not only possible, it’s become an evolutionary imperative that we see and be without a center.

Martin LeFevre