It’s been said, “It never quite feels like the Olympics until track and field starts.” That’s probably because track and field is the oldest competition, dating back to the original games in Greece.

However, as a former amateur sprinter, I’ve never felt so indifferent about the Games. These Olympics feel as empty as the stands, and seem as silly as watching the clutches of family and friends go bonkers over their hometown heroes.

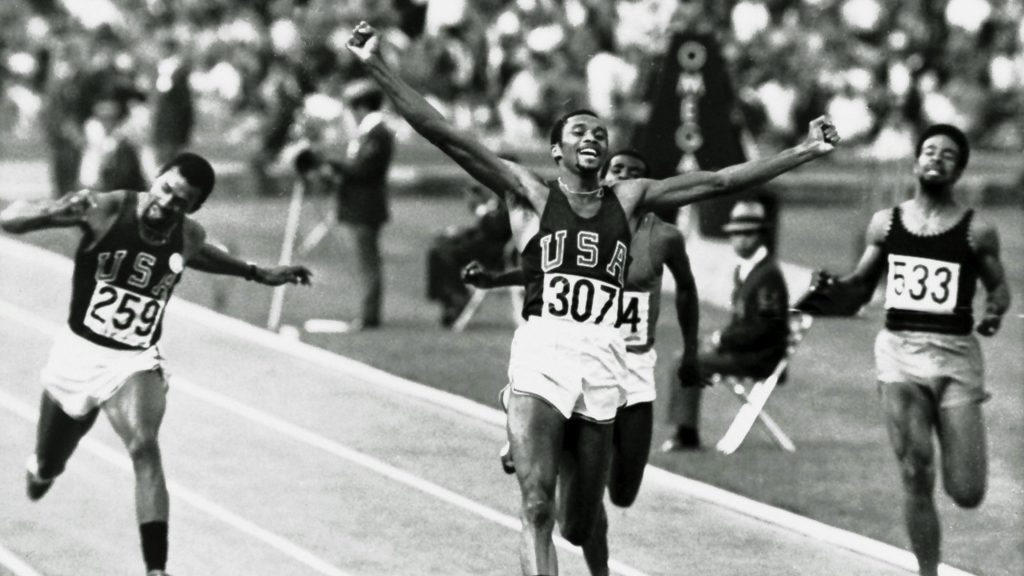

Arguably the best track team that ever competed in the Olympics was the 1968 American contingent to Mexico City. Americans broke a slew of world records, most notably Bob Beamon’s stupendous long jump, which shattered the world record by nearly two feet. That was also the Olympics when John Carlos and Tommy Smith raised their black-gloved fists on the podium for the 200 meters in protest of racism in America.

The 1968 Olympic American track and field team represented the brief pinnacle of American dominance not only in sports, but also science and technology, and geopolitics. Despite the lengthening shadows of Vietnam and racial injustice, both of which persist in perverse forms to this day, the confidence of America seemed limitless. A year after Beamon’s incredible leap, Neil Armstrong made “one giant leap for mankind.”

The coach for the storied ’68 Olympic track team was the renowned and beloved Peyton Jordon from Stanford. After Carlos and Smith’s protest on the victory stand (as shocking at the time as Beamon’s leap), Peyton was pressured to take the entire team home. He refused, but Smith and Carlos were stripped of their medals, and never competed again.

Despite that injustice, the Olympics at that time held more meaning than individualistic glory and nationalistic medal count. For one thing, you still had to be an amateur to compete. Second, the Olympics weren’t the monstrously commercial media spectacles they are today. Finally, though the International Olympic Committee was an autocratic, white man’s club, the Olympic ideals of solidarity and unity of humankind still held sway. A far cry from today.

When I returned to finish my last year of college at 30, I went out for the track team. A couple months before the training season started in January, the podunk college in the geographical center of California had installed a new track. Living across the street, I watched as the workers painted the lane lines.

I hadn’t run in nearly 12 years, but had an itch to sprint again, so I asked when the track would be ready. “In an hour,” one of the workmen said. I returned with my old high school spikes and was the first to run on the red, springy surface.

Feeling slow but enjoying the workout, I watched, incredulous, as an old, fit fellow walked onto the track and began to warm up for a sprint workout. He was in his 70’s if he was a day, but his legs looked as muscular as a young man’s. I introduced myself, and learned that Lamar was competing in age-division Masters meets at 75.

The movie “Chariots of Fire,” a portrayal of the 100 and 400-meter races in the 1924 Olympics, had come out a couple years earlier, and Lamar had actually competed against the Americans portrayed in film. His mind was so sharp and his body so fit that in half hour he completely obliterated my ideas and images of aging.

When I told Lamar that I always wanted to run college track, he laughed. “Then do it,” he replied, “you still have 98% of whatever speed you had at 18.” (In those days, the conventional thinking was that your sprinting days were over by 25.)

So I went out for the track team, though I was viewed as the old guy who would run on a couple ‘B’ relay teams. My goal was to break 50 seconds in the 400, which I felt I could have done my senior year in high school, but competed in the 100 and 200 to win more team points.

Unless you’re in really good shape for the one-lap, 400-meter sprint, it feels like a ‘bear jumps on your back’ at 300 meters as lactic acid builds up and the muscles shut down. In the first meet, I ran a painful, pathetic 56-second quarter, but by the end of the four-month season, I made my goal in the last meet, running 49.7, and placing 4th in the conference meet. Lamar was the timer for my race.

I competed in age-division meets over the next 15 years. My last race was in Los Gatos California at an all-comers meet known for hosting everyone from Olympic athletes to kids running their first races.

That day I watched, amazed, as an 80-year old fellow ran a 200-meter race in 30 seconds flat. Shortly afterward, I lined up for my 400. I took lane 4 and a serious, focused fellow took lane 3.

Immediately I sensed it would come down to the two of us, and that he was faster than me at 100 meters. I hadn’t been working out on a track, but had been doing 500-meter intervals on the street (not recommended because of hard pavement).

Intuiting the guy would go by me coming off the turn into the last 100 meters of the race, I thought, ‘I’m 4 or 5 inches taller; if I don’t quit, and relax, I may be able to lengthen my stride and beat him.’

Sure enough, he went by me coming off the final turn. I relaxed and lengthened my stride, and each stride thereafter closed the gap slightly. I caught him just before the finish line, and won by an inch. It wasn’t the fastest quarter I ever ran, but it was the smartest and strongest.

After congratulating my competitor on a good race, I turned to see the old gentleman who I had watched run the 200 meters. “That was an excellent race,” he said. I thanked him as I struggled to catch my breath.

A fellow about my age walked over and said, “Do you know who that was?” No, I replied. “That was Peyton Jordon. When he tells says you ran a good race, you really did.”

Now the bear is on all our backs. All I want to do is finish the race, even though our age, which has nothing to do with age, is losing the human race.

Martin LeFevre