“We are all Greeks,” the saying goes. It means that the Western mind was stamped in ancient Athens, and we cannot escape our heritage. Only by understanding its present movement within one can we move beyond it and bring about a new mind.

As much as I’ve studied and been influenced by Eastern philosophy and ways of thinking, I am a man of the West. Indeed, in more ways than one, since the Mid-West, whence I hail, was once the American frontier, and California, where I’ve made my home for decades, is as far west as one can go, literally and metaphorically.

As much as I’ve studied and been influenced by Eastern philosophy and ways of thinking, I am a man of the West. Indeed, in more ways than one, since the Mid-West, whence I hail, was once the American frontier, and California, where I’ve made my home for decades, is as far west as one can go, literally and metaphorically.

I make no apology, as many who share my political views do, for being a Westerner. Despite the unprecedented crisis of the Western mind, with its history of rapaciousness of peoples and the earth, and now with its perpetual war mentality, the way ahead, I am convinced, is not through trying to import the Eastern mind into our way of thinking. Rather, by looking within, questioning and observing our thinking and feeling, without losing the Western scientific approach and achievements, we can bring about a new creative explosion.

To put it simply but not simplistically, and make a distinction without reinforcing duality, the Enlightenment in the West has been externally oriented, whereas enlightenment in the East pertained to the inward realm. Whether these two fundamentally different orientations had to arise historically is moot; they did arise. The Western and Eastern minds were stamped from different presses, and moved along different tracks until the last few decades, culminating in the domination of the Western mind.

Socrates, one of the wellsprings of Western philosophy (albeit one that dried up, since his approach of continual questioning lost out to lesser minds’ overvaluing the accretion of knowledge) said: “Education is the kindling of a flame, not the filling of a vessel.” That is a very Eastern insight.

Ironically, now that the Western mind has essentially become the world mind, the Enlightenment has dead-ended. Though media and political “guardians” are naturally still in denial, Westerners are desperately trying to import Eastern ways of thinking to infuse the value-less, moribund and meaningless cultural atmosphere that pervades America and Europe.

However this existential challenge affords a great opportunity to revisit our roots, and create something new. A new, worldwide creative explosion is urgently necessary, and increasingly possible—despite and because of the growing endarkenment of human consciousness.

The question, now that the outward movement has reached its limit (space travel no longer fires the imagination, and is becoming as boring as any other commercial enterprise) is: Can people in the West turn inward in a true and healthy way, without the Western mind losing its capability for reason, scientific discovery and technological innovation?

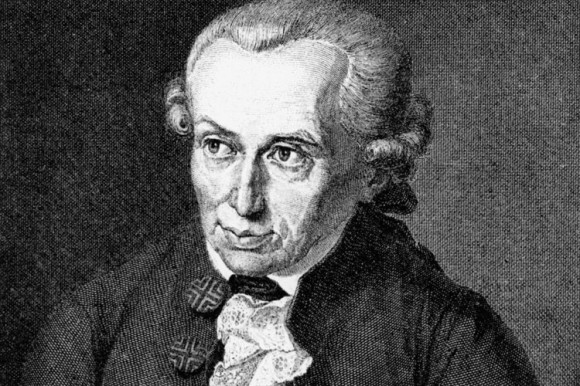

In tracing the roots of the present civilizational impasse, it’s illuminating to read Kant’s seminal essay, “What Is Enlightenment?” Kant’s longer tomes make for impenetrable reading, but this is an uncharacteristically concise and clear essay, worth reading and reflecting on given the end of ‘The Enlightenment’ we’re experiencing in North America and Europe.

Kant did not whitewash the status quo of his time, and the truths he evinced reverberate for global citizens today. Nor did he mince words:

“Laziness and cowardice are the reasons why such a large part of mankind gladly remain minors all their lives, long after nature has freed them from external guidance. They are the reasons why it is so easy for others to set themselves up as guardians…. these guardians make their domestic cattle stupid and carefully prevent the docile creatures from taking a single step without the leading-strings to which they have fastened them.”

He goes on to say “enlightenment requires nothing but freedom–and the most innocent of all that may be called ‘freedom’: freedom to make public use of one’s reason in all matters.” Certainly enlightenment requires freedom, but it’s immeasurably greater than “making public [or private] use of one’s reason in all matters.”

Enlightenment goes far beyond the capacity to reason well and think for oneself. Reason is important, but it is a tool and check, not a value and goal.

“A revolution may bring about the end of a personal despotism or of avaricious tyrannical oppression, but never a true reform of modes of thought,” Kant correctly averred. Of course, he was referring to a physical and political revolution. What he seems not to have grasped is that a psychological revolution can bring about “a true reform of modes of thought.”

Reason has its place, but insight, whether the ‘aha’ moment of insights that we all have, or the state of insight that comes with complete negation in meditation, far supersede reason.

So let’s ask anew: What is enlightenment? Enlightenment neither makes reason its cornerstone, nor does it deny reason through a reaction of some form of Romanticism. Moments of enlightenment, in the language (if not the compass) of neuroscience, occur when the observer and self fall away, and the mind/brain are completely still.

As undirected attention grows, the movement of memory and time (which is thought) spontaneously fall silent, allowing the brain to come into contact with and be infused by sacredness and love beyond the mind of man.

Is full enlightenment when the brain is free of the past and time, and dwells irrevocably in the present, while still being able to fully function in the world? That implies a transmutation in the brain, which, when it occurs in a sufficient but unknowable number of human beings, will ignite a revolution in human consciousness as a whole.

Martin LeFevre