Theoretical physicist Leonard Susskind, a professor at Stanford, says, “The fear of death was hardwired into our genetic makeup in the deep past.” That’s a dubious premise.

He goes further however, confusing the human fear of death with the universal animal instinct for survival. In the next breath he says, “Even worms flee danger.”

He goes further however, confusing the human fear of death with the universal animal instinct for survival. In the next breath he says, “Even worms flee danger.”

Just as it is important for philosophers to be careful about making statements about science, it’s important for scientists to be careful about making statements pertaining to religious philosophy. When Susskind declares that “fear of death may be our deepest instinct—as deep or deeper than the urge to reproduce,” he is on thin ice indeed.

For one thing, the fear of death is not an “instinct” at all, but part of the human condition, an existential orientation in humans. To assert that all animals, “even worms,” have a fear of death is anthropomorphizing.

It is not splitting philosophical hairs to point out that an animal fleeing danger and fighting to survive is not the same thing as an animal fearing death. I submit that only humans fear death, because only humans have knowledge of death and time. Animals, probably even higher mammals such as bonobos, orcas and crows, probably don’t know they are going to die.

Even more dubiously, a pair of experimental psychologists, whatever that is, who have developed something called “terror management theory,” whatever that is, claim, “Much of human behavior is motivated by an unconscious terror of death.”

In their view, “what saves us from the terror of death is culture, since cultures provide ways to view the world that ‘solve’ the existential crisis engendered by the awareness of death.” Hold on there Harry and George.

No doubt that the fear of death is a very basic motivator in human psychology, but it certainly does not lie deeper than the urge to reproduce. And it’s clear that cultural conditioning, in the form of religious beliefs such as the notion that “one’s god is all-powerful, or heaven is a place of unearthly delights,” served in the past to mitigate the fear of death.

But it is a long way from these reasonable premises to the ideas that the fear of death is “hardwired,” and culture “saves” us from the “terror of death.”

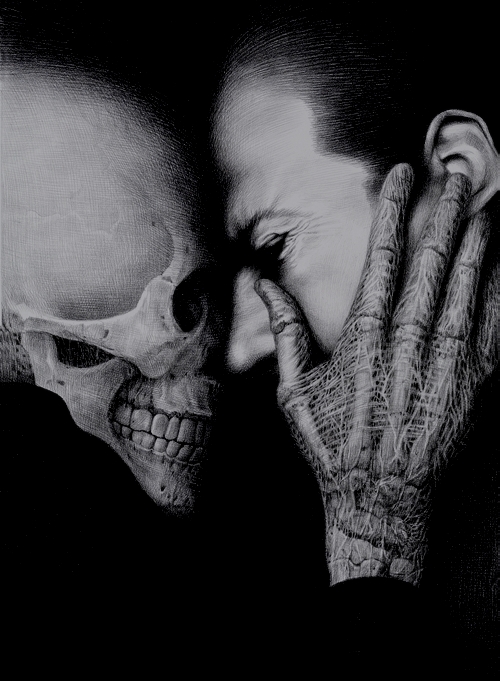

What is the source of the fear of death? It seems a ridiculous question. Death obviously. But though the question is simple, the answer isn’t so simplistic. It may not be death at all that we fear.

To my mind we don’t actually fear death because you can’t fear what you don’t know. What we fear is the ending of the self, of ‘me.’

As I see it, the survival instinct has been hijacked by the desire for permanence, which is a byproduct of psychological time, which in turn stems from the continuity of conscious thought, especially where identity and image are concerned.

Normally, I have such fear like everyone else, but when meditation spontaneously ignites during passive observation in nature, the ‘me’ dissolves in awareness. When that happens, the omni-present actuality of death is seen and felt without morbidity or fear, and it is “the new normal.”

At that point one experiences something beyond all knowledge, beyond all knowing, beyond the word and symbol. The brain comes into contact with the essence of life and death in a completely different sense than what know, or think we know, and fear. Indeed, the brain is an inextricable part of the movement of life and death when the mind-as-thought is completely, effortlessly still.

Ending the observer and time is what opens the door to immensity, whether as intimation, or a shattering, mind and body halting wave.

When meditation takes hold within one everything goes—everything I think, everything I know, everything I’ve felt. The brain is not only completely quiet; it is completely empty. Time stops. One enters the house of death without a trace of morbidity or fear.

After all, death is going on all around and within us every moment, but the mind-as-thought, which is based on continuity of memory and the programs of the self, fears it and pushes it away. When death is a present actuality, one feels tremendous love, which may be the strangest and most beautiful paradox of all.

Death takes everything at death,

So let it take everything during life.

Then one is reborn every day.

Then when one dies is there death at all?

Martin LeFevre