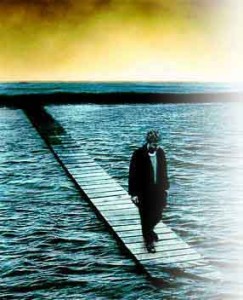

I pretty much lost my 20’s to depression. But I was nearly 30 before I found out what beset me in vicious cycles of abyss and functionality. It was the ‘70’s, before the pandemic of cultural depression, with its vast new market for powerful new drug therapies.

Having gone to a number of therapists to try to understand why I was cyclically unable to move for days on end, it wasn’t until I talked with a psychiatrist that I had a name for it. “You have clinical depression, and need to be on drugs,” he said matter-of-factly.

Having gone to a number of therapists to try to understand why I was cyclically unable to move for days on end, it wasn’t until I talked with a psychiatrist that I had a name for it. “You have clinical depression, and need to be on drugs,” he said matter-of-factly.

Relief at knowing what ailed me immediately gave way to the prospect of taking anti-depressants, possibly for the rest of my life. Though I wasn’t meditating regularly at the time, I’d had so-called mystical experiences since my teens, in which the mind would fall completely silent, and ecstatic states of insight would ensue. Artificially messing with brain chemistry wasn’t something I wanted to do unless it was absolutely necessary.

So after thoroughly researching the affliction, I kept a careful journal, in which I charted the cycles and their triggers. I also started meditating daily, and began running again. In short, I quit internalizing the sickness of the family and society, and took complete responsibility for the darkness and illness within me.

The first step was fully admitting to myself that I was a depressive. From there, I could begin studying depression’s warning signs and observing its cycles without self-judgment (one of depression’s wellsprings). I also traced family origins, including scapegoating, which played a big part in my depression (despite or because of the fact that family members were all depressed to some degree).

I soon saw that anxiety was a key factor. If it persisted for more than a few hours, the pit yawned and swallowed me. Then a full-blown biochemical reaction set in, and with it, a physical torpor bordering on paralysis.

Rather than run away from the anxiety, as nearly everything in America encourages us to do, I began to see it as a huge red flag that demanded immediate attention and action. That involved easing up emotionally, as well as resting, reflecting, and setting aside obligations and expectations.

Anxiety is free-floating fear, seemingly without any clear source. When it takes hold, it’s a state of being, rather than one emotion amongst others. For me, if it persisted, I inevitably began circling the drain.

After a couple more times of getting sucked under, I saw clearly that if a certain biochemical threshold was crossed after a period of sustained anxiety, a depressive episode was inevitable. Then there was nothing I could do except let the depression run its course.

It’s a different thing for bipolar people, who spike as high as they sink, or for chronic depressives, who have deep-rooted affective disorders. There are also clinical depressives who don’t have cycles of normal feeling, and don’t come out of the bottomless pit of darkness in consciousness, which is hell. Anti-depressants have been and continue to be a lifesaver for many such people.

affective disorders. There are also clinical depressives who don’t have cycles of normal feeling, and don’t come out of the bottomless pit of darkness in consciousness, which is hell. Anti-depressants have been and continue to be a lifesaver for many such people.

During my transitional period, I began to look at depression in the same way I looked at getting a bad flu or cold. Once you have it, you have to treat yourself well to get better as quickly as possible. That doesn’t mean being self-centered, but seeing the necessity of taking care of oneself as an objective matter of emotional, spiritual, and even physical survival.

At the same time, I took full responsibility for the mistakes that I’d made that had precipitated another episode. That really helped my learning curve, since the biochemical component of clinical depression has a psychological and emotional basis. This simple fact is largely ignored as family physicians without psychiatric training, in an unholy alliance with a plethora of therapists possessing only Master’s degrees, prescribe anti-depressants like antibiotics.

Having essentially cured myself of clinical depression, I’ve watched with increasing dismay as the drug/psychiatric industry diagnoses depression for everything from mourning the needless loss of the nation’s and the individual’s soul, to alleviating the pain from losing one’s soul mate.

I realize that most people couldn’t come back from the brink without help as I did, and I also realize that if my depression had continued, or gotten any worse, I would have needed anti-depressants. But I am sure that anti-depressants are drugs of last resort, not first resort as they’ve been pushed and prescribed.

In the throes of depression, it’s essential not to come down on yourself. That’s no easy feat, since depression is to a large degree a disease of internalizing what are euphemistically called ‘environmental factors’ of family and society, and blaming oneself for crap that one had nothing to do with producing.

Again, I recognize that some acute depressives don’t have cycles in which they experience normal emotional life (that is, the full range of human emotion), and some don’t come out of the pit. I truly empathize and sympathize with them. For such people, drug therapies are a necessity, even a matter of life and death.

For others, though they may suffer less acutely than I did, depression is more persistent and chronic. I feel the vast majority of depressives in America’s globalizing culture of darkness and deadness fall into this category. And the pharma-psychological industry has increased the epidemic of depression by individualizing unaddressed collective cultural conditions and man-made realities, and that is unconscionable.

For others, though they may suffer less acutely than I did, depression is more persistent and chronic. I feel the vast majority of depressives in America’s globalizing culture of darkness and deadness fall into this category. And the pharma-psychological industry has increased the epidemic of depression by individualizing unaddressed collective cultural conditions and man-made realities, and that is unconscionable.

I’m sure that a sizable portion of the population in America, Canada, and Europe on anti-depressants need not be. I’ve known people who get on anti-depressants after the break-up of a romantic relationship for God’s sake. And I met a woman who was the chief therapist of the local college’s professors (with a Master’s degree only ironically) who said that nearly half of them were on anti-depressants, including her for ten years.

“I want to get off them, though,” the therapist said, “because I’m noticing a flattening effect to my affect.” No kidding.

Let’s face it, we’re a quick-fix nation and culture; the notion of taking six months to gain mastery and management of depression is not something most people want to do, nor is it something the psychological sector is prepared to provide. Of course it doesn’t help that drug companies are pushing the miracles of psychoactive drugs in commercials with wildflowers and meadows.

It’s been nearly 30 years since I’ve had a full-blown episode of acute depression, the kind where I couldn’t get off the couch for three or four days. Even my mother’s death over a year ago, with all the family stuff it brought forth, didn’t send me over the emotional cliff.

But after “the Good Bush,” George H.W. Bush’s Gulf War, I went into a deep funk. Having known depression inside out, I felt it wasn’t that, but couldn’t shake the persistent mood.

I was living in Silicon Valley at the time, and a few times a week for several weeks I walked the hills overlooking South San Francisco Bay, asking, ‘what is this feeling?’

Some angel may have gotten sick of my question, because walking after a mind-quieting sitting, I heard, for the first and only time in my life, a clear voice that didn’t seem to come from my own head. “You’re in mourning,” it said emphatically. With the relief that comes from finally knowing what ails you, I exclaimed, ‘That’s it!’

Within seconds I asked the obvious next question: What am I mourning? “You’re mourning the death of your nation’s soul” came the immediate reply in the same emphatic tone.

That was 1991, and the epidemic of national depression was about to begin. There is no drug that can cure it; only facing the fact without internalizing it can.

Martin LeFevre