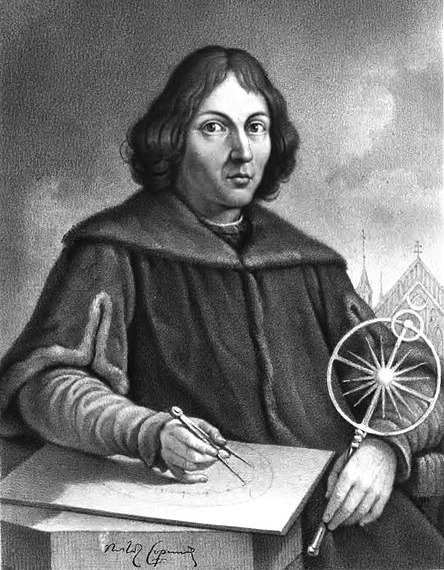

In the first century, the Greek astronomer Ptolemy, working in the great library in Alexandria, produced his earth-centered system of the universe. The Ptolemaic world-view held sway until the 16th century, when Copernicus proved that the Earth revolved around the sun.

Einstein in turn overthrew that paradigm, showing that all centers are relative and in flux, and that no point is permanently fixed in relation to others. There is no center in the universe as it actually is.

Einstein in turn overthrew that paradigm, showing that all centers are relative and in flux, and that no point is permanently fixed in relation to others. There is no center in the universe as it actually is.

Psychologically however, we cling to the Copernican, if not Ptolemaic, way of seeing the world, and that is producing more and more egocentrism and ethnocentrism. Self-centeredness, like primary identification with particular groups, inevitably increases the divisions and disparities between people—economically, politically and socially.

Science is about interpretation, not truth, as a recent study of sensory perception attests.

English-speakers are poor at accurately naming even common smells like cinnamon with their eyes closed. Researchers found that rain-forest foragers on the Malay Peninsula (I wonder how they became objects of scientific study) were about as capable of naming what they smelled as they were of naming what they saw. Scientists have concluded from such discrepancies that ‘sensory perception is culturally specific.’

Stop the presses! Anthropologists have discovered that ‘metaphors can be powerful enough to disrupt perception!’ It hardly takes a scientist, or even a poet to know that. When was the last time you heard a croaking frog? Just now, in your head?

In actuality, amphibians are dying off quickly all over the world. Learning how to listen, see and feel what humans are doing to the earth through the improper use of ‘higher thought’ has therefore become tremendously important.

Obviously we all tend to see things from our conditioned perspective. Indeed, most people almost never look at nature and the world without a center, which is to say without a self.

Superficially, everyone has a different perspective. Culture, education, religion, and even the climate affect how we see things, which varies from place to place and person to person. In one sense, these varying backgrounds make for variety, and diversity. But far more often these conditioned differences make for division and conflict.

To look from other people’s perspectives is to see the world through other people’s eyes. That’s certainly a good thing. But in observing without the observer/center, the particular, conditioned perspective ends. Unwilled attention and direct perception in the present restores the brain’s capacity for wholeness.

Through methodless meditation, one learns how to look from no particular perspective, that is, not from a center at all. Learning how to listen and look in the present is the key to opening one’s eyes and freeing one’s mind.

Then who or what is looking? There is no separate entity, and so there is no center. There doesn’t need to be an observer for observing to occur. Indeed, the observer prevents true observation.

There is a huge difference between saying that the senses are usually conditioned, and declaring that sensory perception is culturally specific. What is behind such bias toward bias?

What is behind such bias toward bias?

The conclusion that sensory perception is culturally specific is another attempt to deny the universality of human nature and experience, and assert the primacy of the self, as well as cultural and national identity. And that’s very harmful to the human prospect in the formless maelstrom of the global society.

The point is not that our senses are unconditioned, but that in attending to sensory input in the present, we become aware of how they, and our minds and our hearts, are conditioned. That awareness, when it is sustained without judgment and evaluation, dissolves the accretions of memory that occlude sensory perception and spiritual insight.

Therefore to assert the ‘cultural training of attention’ is not only wrongheaded; it willfully misunderstands the nature of attention and its paramount importance in human freedom. Spiritual insight isn’t a matter of rising above the senses, but of unconditioning the senses and the mind in attention to what is.

When conditioned differences are primary, there is inevitably division and conflict. The most confused people think conditioned differences are good; the average person thinks they are an unchangeable aspect of being human. Paradoxically however, genuine uniqueness and diversity within and between people is only possible when the divisions of difference end.

A flock of small birds lands in the shallows, and a few begin beating their wings furiously in the water. More join in, and suddenly there are a dozen birds taking a bath at the same time.

They all seem to be great friends, thoroughly enjoying the late-afternoon splash. One by one they dart off, flying downstream even as others fly up. It is a marvelous sight, so full of movement and life.

Watching everything outside and inside on the mild afternoon, meditation flows in like a soft breeze through the leaves. As always, it comes completely unbidden, when effort and goal- seeking have dissolved in passive awareness.

The senses open, memory and association fall silent, and nature and the world are seen anew. And in seeing anew, one is renewed, and liberated.

Martin LeFevre