Magnificent formations of white cumulus hang over the foothills, mountains in the sky above mountains of the land. Though the town is full of parents and siblings for graduation ceremonies, there are few cars at the gated end of Upper Park.

I had intended to take a sitting at a secluded spot at the upper end of Lower Park, but why meditate in a hole when you can meditate in paradise? In nearly two hours, only half dozen people pass by on the path behind me.

After half hour, I hear a voice across the gorge above the roar of the stream below. It’s a young man with a cell phone plastered to his ear walking up the canyon.

A half hour later he walks back, still talking on his cell. It’s so incongruous in the stupendous beauty that I say hello. But he doesn’t hear me, lost in his isolated socialness. Why are so many people unable to be alone, even when by themselves?

Spontaneous stillness and reverence is the mark of meditation. One cannot seek the sacred. It comes when passive awareness has gathered sufficient attention to negate the operating program and the contents of the self.

Though functional memory is obviously necessary, most of our memories are useless, the fetid soil of hurts, grudges and depression. Psychological memory may have defined us as human, but it is preventing us from growing into human beings. Let the computers have memory.

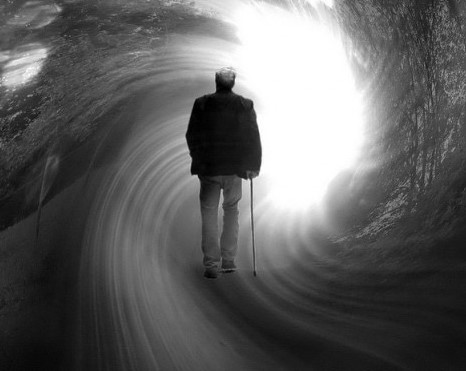

We don’t fear physical death; we fear psychological death. And even if reincarnation is a fact, psychological death is a certainty. ‘I’ am going to die.

The self is a program of memory over time. Sorrow is memory infecting emotion. If we learned how to let go of our memories and die psychologically every day, would there be death when we expire?

Sitting on the lip of the gorge, with a view up the canyon for miles, there is the insight that the earth itself is held in the cup of death, as is every planet and star.

Death is the ground of life, and of the universe itself. The ever-present actuality of death is what allows creation to be recapitulated every moment. Only humans grow old. Not physically, which is natural and inevitable, but psychologically, inwardly.

In Lord Byron’s last poem, “On This Day I Complete My Thirty-sixth Year,” written in Greece a few weeks before his death, he grapples and comes to terms with the impasse of his age. “But ‘tis not thus—and ‘tis not here—/Such thoughts should shake my soul, nor now…”

It’s one thing for one’s people, country and culture to perish, as America has; it’s another for one’s age to be fruitless. The first phenomenon is very difficult to deal with, but the second “should shake my soul.” But is our age hopeless?

Byron resolved his existential crisis by connecting with ancient Greece, the wellspring of Western civilization: “Glory and Greece, around me see!…Think through whom thy life-blood tracks its parent lake, and strike home!”

We in the West no longer have that option. The parent lake has dried up, and we stand alone. Can we create a new culture with others who also stand alone?

Consciousness as we’ve known it for tens of thousands of years no longer holds meaning and has coherence. We have only two options now. We can continue to accumulate memories and programs, becoming less and less human and more and more like the thought machines we’ve made in our image.

Or we can embark on the journey of negating conditioning and its contents through attention and insight, growing into true human beings. Whether that radical change begins in our age or not, it’s the way ahead for the individual and humanity.

Martin LeFevre