To everything (turn, turn, turn) … there is a season (turn, turn, turn) … and a time … to every purpose … under heaven. So true, Bible. So true, Byrds. What the truisms neglect to tell us, however, is that “every purpose under heaven” includes not only planting and reaping and laughing and weeping, but also,apparently, performing porny Google searches.

We know this, now, because of the plantings and reapings of Science. According to a paper just published in the Archives of Sexual Behavior, Internet pornography — like so many storms, like so much kale — is seasonal. Porn’s peak seasons? Winter and late summer.

We know this, now, because of the plantings and reapings of Science. According to a paper just published in the Archives of Sexual Behavior, Internet pornography — like so many storms, like so much kale — is seasonal. Porn’s peak seasons? Winter and late summer.

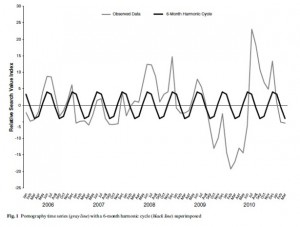

Researchers at Villanova examined the Google trends for such commonly-searched-for terms as “porn,” “xxx,” “xxvideos” … and other, more descriptive phrases that, because I am looking at a portrait of James Russell Lowell as I write this, I will let you look up in the paper itself. Once they’d gathered those terms, the authors examined them in Google Trends. And what they found was a defined cycle featuring clear peaks and valleys — recurring at discernible six-month intervals. The cycle, as you can see in the chart above, maps surprisingly well to the world’s calendar seasons.

Other searches don’t. The researchers also ran a control group consisting of Google searches for non-sexual terms. And those terms demonstrated no such cyclical pattern.

So there’s something about sex itself, it seems. Porn is periodical. Which is born out by another (semi-)control in the Villanova experiment. Researchers determined search terms associated with a relatively purpose-driven category of sexytime — prostitution and dating websites — and found that, for those terms … the six-month cycle showed up again.

Which: fascinating. The seasonal Internet! The sex-seasonal Internet!

Now, sure, this is one study, and, sure — as always — there is more work to be done. (For example, what would happen if the terms were changed or broadened? And, per this research alone: What happened in late 2009 and early 2010 to make porn-related searches plummet and rise so sharply? Was the world reacting, a bit belatedly, to the global financial meltdown? Did people suddenly get better broadband connections?)

As they stand, though, the findings are striking. And they suggest, above all, the power of the Internet to reveal the patterns of human emotion in a new scope, from a new angle. The Internet knows what we want. It knows what we do when we are alone, or think we are. And it knows all of us with the same totality of intimacy. As the blog Neuroskeptic points out, the researchers’ findings could “reflect a more primitive biological cycle” — something profound in the complex dynamic among biology, technology, and the world of flesh that mediates the two.