The smaller of the two creeks, just beyond town (and soon to be enveloped by it), is running full and strong again after a few good storms. One almost forgets that for over three months during the dry season it is a stream of stones.

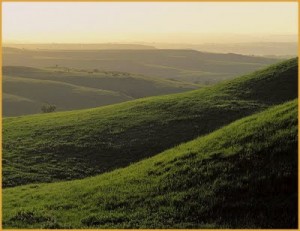

The hillsides are beginning to green, and in another month the first wildflowers will appear. Despite a cold, brisk wind, I take the full loop on the bike, passing flat fields with gently ascending foothills beyond. The higher, secondary slopes in the distance display patches of new-fallen snow.

The hillsides are beginning to green, and in another month the first wildflowers will appear. Despite a cold, brisk wind, I take the full loop on the bike, passing flat fields with gently ascending foothills beyond. The higher, secondary slopes in the distance display patches of new-fallen snow.

I sit under the big sycamore facing the fields and the canyon beyond town. The city’s ‘viewshed’ has been marred by a long string of monster houses that the city council allowed to be built along the ridge in the last few years, but the volcanic cliffs some miles away are still a stupendous sight on a clear day.

A type of falcon, a kite, is hovering over the fields about 200 meters away, its long, slender wings rhythmically beating the air. Fluttering over a single spot for 20 seconds or more in search of prey is one phase of its distinctive flight pattern. Suddenly it tucks its wings back and plummets to the ground in an arc of pure gracefulness.

The kite disappears after that first sighting. But then, about a half hour later, just as the mind spontaneously falls silent in passive observation, it suddenly reappears and hovers directly in front of me across the stream.

In a meditative state, nature leaps forth, and the world recedes.

Why does the human mind have a seemingly infinite capacity for illusion—what Buddhist’s call delusion? That’s a central question of both philosophy and spirituality.

There’s a tendency among Buddhists to make what philosophers call a category mistake by saying that because the mind inhabits an illusory world of its own making internally, the manufactured world outwardly is also an illusion. However, the inner world and the outer world of individuals and societies, while inextricably related, are different realities.

The human mind generates the separations and divisions that give rise to the realities of this terrible world, but wars, poverty, and ecological destruction are very real, and cannot be denied by labeling everything illusion, or ‘maya.’ The mind fabricates the illusion of duality, of ‘me vs. you,’ and ‘us vs. them,’ but the conflict and disparity that result are very real.

Our mental worlds are illusory, not in the sense that they don’t exist, but because when the symbolic activity of words and images, memories and associations dominate, one cannot see clearly. Even so, the outer world based on psychological division that the mind and hand construct is very real, both physically and in terms of the suffering generated.

Is it possible to live without illusory mental worlds? Can one look without the filter of symbols and memories, and see nature and the world as they actually are in the moment? Most philosophers say no, that we are inherently ‘hermeneutical’ or interpretive creatures. But that’s false, and gives a lie to meditative states.

The human mind has a powerful tendency, buttressed by the habit of thousands of years, to do two things: separate and store. At bottom, the human adaptive pattern rests on these two abilities, which have enabled our manipulation of nature, and the accretion of knowledge.

Just as the waves aren’t separate from the sea, and currents are inseparable from the ocean, matter and energy interpenetrate each other. And just as ‘things’ such as trees aren’t separate from the earth, ‘sovereign’ nations aren’t separate from humanity, no matter how much regressive identification of people in a globalized world may wish it so.

Just as the waves aren’t separate from the sea, and currents are inseparable from the ocean, matter and energy interpenetrate each other. And just as ‘things’ such as trees aren’t separate from the earth, ‘sovereign’ nations aren’t separate from humanity, no matter how much regressive identification of people in a globalized world may wish it so.

There is no separation of anything in actuality. When there is direct perception of this fact at an emotional level, one ‘feels’ the numinous.

Because the vast majority of people are surrounded all day with man-made worlds, and because most aren’t self-aware and self-knowing about the workings of their own minds, the distinction (not duality) between nature and the world is lost. The illusory worlds of science and technology come to be thought of as all there is, resulting not only in further alienation from nature, but the loss of one’s soul.

Point to something and ask a young child whether people made it, or whether nature did. Most children have no trouble making the distinction, without duality, and yet most adults, blinded by the illusions of the world and their own thought, lose their ability to make such a distinction, or feel that it matters.

No matter how difficult the paths we walk we don’t have to contribute to the divisions and delusions of this world through one’s own distorting mental and emotional activity. However, one has to learn the art of undivided and undirected observation, which is essentially a movement of negation. Otherwise, one is ineluctably overwhelmed by cognitive and emotional accumulation, which shrinks the mind and deadens the heart.

When one observes all streams, inward and outward, illusory and actual, without division, the stream of thought effortlessly ends. Then there is simply seeing and being, from which goodness flows.

Martin LeFevre