The strictest monks in Catholicism are “Cistercians of the Strict Observance,” usually known as Trappists. They pray six times a day, beginning at 3:30 a.m. Thomas Merton was a Trappist, though he never quite fit the mold.

There are only 16 Trappist monasteries in North America, and one of them, New Clairvaux Abbey, is only 20 minutes from here.

I initiated a series of dialogues with the abbots (previous and present) and some of the brothers around questions of mystical experiencing and tradition, and the relationship between the contemplative life and the active life. For example, is tradition compatible with direct experiencing of the sacred?

I once heard a religious teacher from India say that just as India had been looked within for centuries, America, the most externally obsessed land, could flip like magnetic poles, and turn within. As the evils and corruption of Trumpism tear at what’s left of the nation’s soul, many Americans are doing just that.

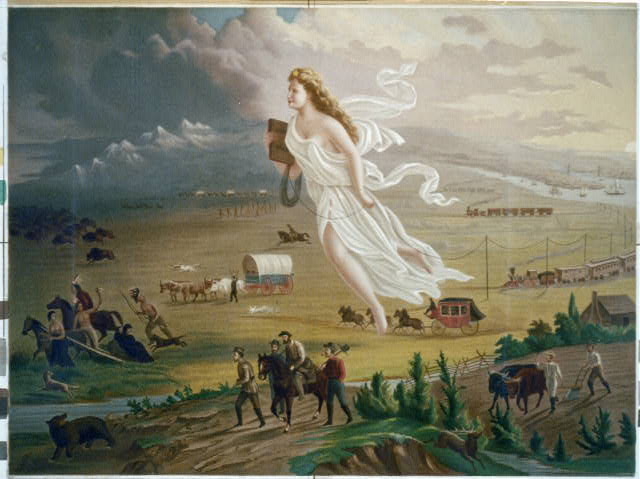

Of course, to be inward looking has a negative connotation in this nation of Manifest Destiny, implying inaction and paralysis. And to be sure, India’s inward looking culture did stymie material progress, and become ossified into a caste system with Brahmins fixed at the top and untouchables fixed at the bottom.

However this is why balance between “vita contemplativa” and “vita activa” is essential. The fact that America ran so heavily toward the active life that it ran off the cliff into a materialistic abyss, only makes an equipoise between contemplation and action all the more necessary.

The monks of New Clairvaux obviously dedicate their lives completely to the contemplative life. But they graciously allowed my inquiry to proceed…to a point.

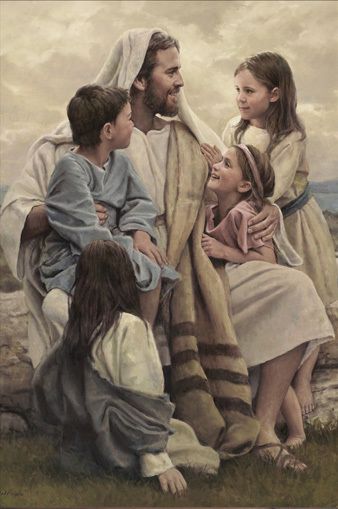

Including two, hour and half long sessions independently with the previous and present abbot, there were eight weekly dialogues. The one that stands out the most centered on the deepest questions about the life and death of Jesus of Nazareth.

At one point in this delicate dialogue, I turned to the most erudite of the brothers, a brilliant man with an interest in Russian mysticism before the communist revolution, and asked a blunt question.

The Bible says, “And at the ninth hour, Jesus cried out with a loud voice, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” It is the only saying that appears in more than one Gospel, Matthew and Mark. Do you think Jesus actually said that?

He said yes, but disappointingly added that Jesus’ last words were from Psalm 22:2. But that’s fudging it, since that psalm reads: “My God, I cry out by day, but you do not answer, by night, but I find no rest.”

That isn’t the same at all. Besides, it just begs the question, why did Jesus say it?

Doesn’t it mean Jesus didn’t understand what went wrong, why his mission failed, and that he felt abandoned by God the Father?

Needless to say, that set off a discussion with the monks. It didn’t become contentious, but it revealed a fundamental difference between the way a mystic views Jesus, and the way a traditional Catholic and Christian does.

The idea that Jesus was both a human being and God just doesn’t cut it. It doesn’t address the mystery of his last words, and insists on having things both ways—one of the worst human tendencies.

My feeling (as opposed to belief) is that Jesus’ was a prophet and exceptional human being, but that mission failed—though he did not fail.

Tentatively, I feel that Jesus did not become Christ until he died. Which is to say, he did not fully merge with the intelligence and love that imbues the universe until he expired.

We say “Jesus Christ” in the same breath, but he would never have done so. Jesus was a human being, and we betray him by making him into a god, much less God.

To my surprise, I found the monks of New Clairvaux to be real individuals. More so than the average

American, who believes, in their conformity to the unexamined tenets of individualism, that they are unique, when actually there are millions of people who think, feel and act just as they do.

New Clairvaux’s winery is ‘trending,’ and draws thousands. But as one retreatant wrote, “The winery now runs the monastery; the monastery doesn’t run the winery.” A deliberate return to tradition, dogma and authority by the present abbot has only hastened the erosion of the contemplative life there.

As Jesus taught, the truth is found within. And New Clairvaux, like all monasteries in this age perhaps, has little to offer those seeking balance between the contemplative life and the active life.

Martin LeFevre