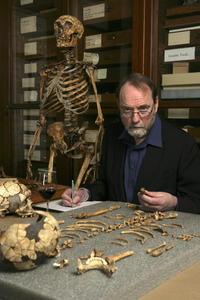

In his book, “Becoming Human,” paleo-anthropologist Ian Tattersall says, “In both the anatomical and the technological realms, the history of our lineage has been one of episodic innovation, and not one of a gradual approach to perfection.”

The idea of gradual improvement is one of the biggest psychological and philosophical impediments to meeting the ecological and existential crisis of the individual and humanity.

The idea of gradual improvement is one of the biggest psychological and philosophical impediments to meeting the ecological and existential crisis of the individual and humanity.

Neither evolution nor human history change in a gradual way, but only when pressure builds up in a system and the status quo can no longer be maintained. The system is now global, and the crisis is consciousness itself.

Though human history does not evolve, the question is whether there is any discernable direction, except increasing technological and economic complexity and the fragmentation of nature and the human psyche. Martin Luther King famously said, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” That may be true, but it isn’t bending fast enough to meet the planetary imbalances humankind is generating.

When modern humans first emerged about 100,000 years ago in Africa (DNA studies indicate in present-day Tanzania), the elements of human evolution over the previous five million years or more came together to produce the human adaptive pattern as we know it.

No matter how much science and New Age thinkers (strange bedfellows indeed!) try to blur or fudge the difference between humans and the rest of nature, our species operates on a completely different principle than nature. That principle is separation, which literally means ‘to remove and make ready for use.’ That forms the root of the human adaptive pattern.

The idea that humankind’s alienation from nature occurred with the Agricultural Revolution, much less the Scientific Revolution, is woefully inadequate. The roots of our alienation are much older and deeper than that, in the evolution of the cognitive capabilities that made us fully human, but incomplete as human beings.

Romanticizing indigenous times and peoples also completely misses the mark. Indigenous people were and are no different than present-day peoples. Rather, they were basically embedded in nature, and didn’t possess the science and technology to manipulate and mess up the environment that we do.

No other animal on earth consciously removes ‘things’ from nature and recombines them according to its mental templates. Humans are alienated from nature and increasingly from each other, and are fragmenting the world all to hell, because we have the capability of separation without the insight into its illusory and utilitarian nature.

It used to be our anthropomorphic habit, especially in the West, to think that Homo sapiens was the culmination of the evolutionary process. Now many people have gone the other way, and believe that Homo sapiens is just another species, indeed, that the earth would be better off without us.

Neither the anthropocentric or misanthropic view of humanity is correct however. Despite rampant self-centeredness, we are not the center of anything. And yet, the human brain is almost certainly the only brain on this planet with the capacity for conscious awareness of the numinous. The human brain matters, to a point.

At the philosophical level, since evolution gave us the capabilities that we are so unwisely using, the  development of conscious symbolic thought poses a huge dilemma, both for us, and for evolution itself.

development of conscious symbolic thought poses a huge dilemma, both for us, and for evolution itself.

The full development of the exceedingly powerful evolutionary adaptation of separative, symbolic thought made us human. But without insight into thought’s inherently separative nature, man has generated increasing division, fragmentation and darkness.

In the past, isolated populations were, in Ian Tattersall’s words, “the engines of innovation in evolution.” But the isolation of populations no longer exists, due to the interconnection and intermingling of people through the jet and the Net.

Tattersall says, “Language, with its associated mental abilities and behavioral complexities, spread and diversified from its place of origin through contact and diffusion among established human populations that already possessed the latent ability to acquire it.”

But he’s describing the present potential for transmutation, not the way the human adaptive pattern spread over the earth in the past. Evidence points to the ruthless displacement of existing populations, through competition and conflict, not the diffusion of linguistic and cognitive capabilities.

“Language is more or less synonymous with symbolic thought,” Tattersall adds, and asks, “Do the conditions now exist for new evolutionary developments out of Homo sapiens?” The answer for him is no, “because the conditions for true evolutionary innovation [the isolation of populations] within our species simply do not exist.”

But Tattersall is adhering to an old evolutionary model, and denying the potential for the rapid diffusion of new insights into the human condition that the interconnected age affords.

The latent capacity for self-knowingly awakening a deepening insight into thought exists in people throughout the world, and will, at some point, bring about a psychological revolution in the blink of the eye.

Is a revolution in consciousness happening, or is humankind heading in the opposite direction? Clearly it’s not happening; indeed, ecological and social fragmentation is accelerating. Is the intensifying crisis driving a radical change in the individual and human species?

The choice is not between delusion and preclusion—believing it is happening, or believing it can’t happen. That’s no choice at all. Do your inner work, ask the big questions, and keep your ear to the ground.

Martin LeFevre