There’s a lot of interest in human origins these days. A new, permanent exhibition, featuring more than 200 casts of pre-human and human fossils, opened a few years ago at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The exhibition addresses three fundamental questions, according to the museum’s president: Where did we come from? Who are we? And what lies ahead for us?

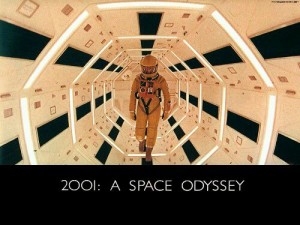

On the same day I came across an article about the exhibition, I happened upon the movie, “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Arthur Clark’s story and Stanley Kubrick’s classic film address the same three questions. Though I was only 16 when it debuted in 1968, the film was the inspiration for my philosophical work in ‘theories of human nature.’

On the same day I came across an article about the exhibition, I happened upon the movie, “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Arthur Clark’s story and Stanley Kubrick’s classic film address the same three questions. Though I was only 16 when it debuted in 1968, the film was the inspiration for my philosophical work in ‘theories of human nature.’

The movie opens with a large, black monolith surrounded by a group of apes. They are displaying innate curiosity, cautiously inspecting and touching the strange object. The monolith remains in the apes’ midst until the right moment, symbolized by the alignment of the sun and moon. Then it triggers a momentous insight in one of the apes.

To the soaring notes of “Also sprach Zarathustra,” our proto-human ancestor pauses amidst a field of animal bones, and has an ‘aha’ moment that kick-starts man’s evolution. He picks up a thighbone and begins smashing skulls with it, first a fleshless skull amidst the field of bones; then the living animal (signifying the beginning of hunting); and finally, the skull of a rival group member (signifying the beginning of war).

The weapon is tossed into the air, and morphs, millions of years later, into the graceful arc of a huge, rectangular space station, famously set to the Blue Danube Waltz. As this and other technological marvels soar through space, the message is clear: all our vaunted technology sprang from that first insight and lethal tool.

The monolith appears again on the moon millions of years later, buried, with perfect placement and predicted timing, to be discovered by the distant descendents of the skull-smashing apes. The mysterious object emits another signal, painfully audible to the astronauts touching it with the same primate curiosity, which directs the humans of our time to a point near Jupiter.

A grand mission is undertaken (while still keeping the Russians in the dark), but HAL, the superhuman  computer brain in charge of all functions on the spaceship, goes haywire, and an epic confrontation between man and machine ensues. Once that supreme crisis has been passed, the surviving human completes the journey alone, his hibernating compatriots having been snuffed out by HAL after his companion astronaut has been sent spinning into space.

computer brain in charge of all functions on the spaceship, goes haywire, and an epic confrontation between man and machine ensues. Once that supreme crisis has been passed, the surviving human completes the journey alone, his hibernating compatriots having been snuffed out by HAL after his companion astronaut has been sent spinning into space.

A scene follows in which HAL’s higher functions are slowly and systematically disabled (“I’m going Dave, I can feel it, I can feel it…”), illustrating a perfect projection of thought’s fear of losing control and self-identity.

“2001” unfolds as a montage of technological prowess and human alienation. For example, there’s a scene where the doomed astronaut, soon to be murdered by ‘HAL,’ is receiving a time and space delayed birthday greeting from his parents as he sunbathes in artificial light. You don’t have to be a billion miles from earth to know such habituated isolation, wordlessly well conveyed by the actor Gary Lockwood as Frank Poole.

Near the end of “2001” there is a wonderful riff on time, with past and future telescoping into each other and converging in the present. The sole remaining astronaut, David Bowman, played by Keir Dullea, has been transported into another dimension, signified by the psychedelic scenes for which the movie is famous.

At first he sees himself as an old man, looking back at the young man in his spacesuit. Instantly he is the old man, seeing himself on his deathbed. Then he’s on his deathbed, and there’s a breakthrough. A new human being is born, floating in space next to the earth, its amniotic sac having a larger circumference than the earth itself.

With a stroke of artistic genius, Stanley Kubrick conveys (probably unintentionally, as artists often do), something of the essence of true meditation, which has nothing to do with concentrating on one’s breathing or sitting in a roomful of people staring at a wall.

With a stroke of artistic genius, Stanley Kubrick conveys (probably unintentionally, as artists often do), something of the essence of true meditation, which has nothing to do with concentrating on one’s breathing or sitting in a roomful of people staring at a wall.

There comes a moment meditating in nature when thought lets go of its illusions and the observer becomes the observed, and time compresses and collapses. Then the infinite regression of thought spontaneously ends, the mind falls completely quiet, and a small breakthrough into a higher order of being occurs. What matters in meditation is attending fully to what comes into ones awareness in the present, inwardly and outwardly, without duality or division as the observer apart.

“2001” provides one answer to all three questions posed at the beginning of this column. As a boy of 16, my mind was fired by the race to the moon, and science fiction discussions with friends. This film took me to new level of questioning, and launched my philosophical vocation. Both hold up nearly 50 years later.

The essential flaw in the book and film, and my later point of departure with it as a young man prone to non-drug-induced ‘mystical experiences,’ is the positing of an outside force prompting human evolution at critical junctures. That smacks of divine intervention, when breakthroughs only occur when humans stand on their own two feet.

In short, there is no outside force; the mystery is much greater and deeper. But ‘2001’s’ portrayal of the growing crisis of humankind–our increasing alienation from nature and ourselves–remains penetrating and prophetic.

Pompous thinkers drone on that advances in human understanding are progressive, pollyannaishly maintaining that technological and spiritual ‘downsides are more than made up for by the upsides.’ They absurdly talk about a ‘galloping spiritual pluralism,’ upholding the enervating status quo with hollow calls to be grateful and upbeat, while willfully denying that America and the West have become a spiritually dead wasteland.

They refuse to see that only with the ending of the old and decrepit can there be the birth of something new. Is it too much to grasp that man himself has died, and to see that the fact has to be emotionally perceived for a new species to be born?

‘2001’ remains accurate and prophetic in another essential way—there is indeed another stage of human evolution, though apparently it can only come about through the crucible of growing darkness and crisis. Even so, a breakthrough is ever more urgent and open to the ordinary person, and more and more people are experiencing intimations of it.

The mouthpieces of the status quo fearfully deny the urgency of radical change, while the many sit on sidelines, either giving up and marching toward the abyss with the walking dead, or waiting for the savior that will never come. We are each our own savior, and the saviors of humanity.

Martin LeFevre