Zika Virus – With the Zika virus cases continuing to grow in Costa Rica, more information on how it is spreading is needed to combat the virus. The latest study involved the spit of the mosquito.

Mosquito saliva might be even more important for spreading infection than anyone thought.

Mosquito saliva might be even more important for spreading infection than anyone thought.

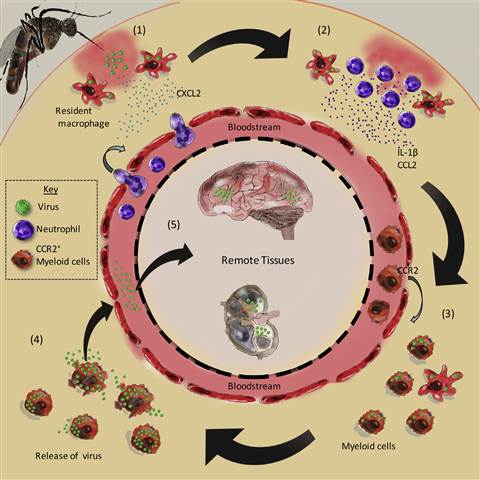

Two studies published in the past week show that mosquito saliva lures immune cells to the site of a bite, and tricks them into spreading any viruses, such as Zika virus, throughout the body.

Tests in mice show that mosquito spit is such an important factor that it could sometimes turn a normally benign viral infection deadly.

“Mosquito bites are not just annoying — they are key for how these viruses spread around your body and cause disease,” said Clive McKimmie, an expert on viruses at the University of Leeds in Britain who led one of the studies.

“We now want to look at whether medications such as anti-inflammatory creams can stop the virus establishing an infection if used quickly enough after the bite inflammation appears.”

Scientists have long known that mosquito bites cause inflammation. Mosquito saliva, which carries chemicals to help stop blood from clotting and to open up tiny blood vessels, stimulates an immune response.

The two teams of scientists wanted to see whether and how this immune response might affect how easily and how seriously mosquito-borne viruses such as dengue and Zika infect people.

For their experiment, McKimmie’s team used mice and Semliki Forest virus, a close relative of Zika, dengue and chikungunya viruses.

They injected the virus into the mice with and without saliva from Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. When the virus was injected without mosquito saliva, it didn’t spread much. Adding mosquito saliva made it spread faster, they reported in the journal Immunity.

Not only that, but adding mosquito spit turned a normally harmless strain of Semliki Forest virus into a lethal infection that killed many of the mice.

They identified a long list of immune cells and immune-stimulating chemicals that showed up when mosquito saliva was injected.

“This research could be the first step in repurposing commonly available anti-inflammatory drugs to treat bite inflammation before any symptoms set in,” McKimmie added in a statement.

“We think creams might act as an effective way to stop these viruses before they can cause disease.”

Another team, led by Eva Harris of the University of California Berkeley, did a similar experiment using dengue virus.

Dengue is spread by the same Aedes aegypti mosquitoes that spread Zika, chikungunya and yellow fever viruses. But dengue comes in four strains that cause strange immune responses. People who are infected with one strain of dengue actually get sicker when they’re infected with another one.

Harris’s team also used mice to see why and whether mosquito saliva affects this odd process.

They found mosquito saliva makes dengue virus more likely to spread and cause infection. It helps the virus infect the very immune cells sent to fight it, they reported in the Public Library of Science journal PLoS Pathogens.

“Mosquito saliva and enhancing antibodies thus need to be considered when developing vaccines and drugs against dengue,” they wrote.

They also tried surgically removing the skin of mice after infecting them with dengue. The surgery saved half the mice if they hadn’t also injected mosquito saliva. But if they had, the surgery didn’t help – the virus had already spread too quickly.

Mosquitoes transmit some of the biggest killer diseases, from malaria to yellow fever.

There’s no treatment and no vaccine against Zika or dengue, although some are in the works. West Niles virus, which is carried by different mosquitoes, can also kill people. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and World Health Organization say the best way to protect against any of these infections is to avoid mosquito bites with repellent, by covering up and by staying inside air-conditioned spaces.

by MAGGIE FOX, NBCNews.com, Edited by Dan Stevens