[In honor of Nelson Mandela, we are re-posting this column, published in 2010, with a few revisions and excisions] The movie “Invictus,” though a bit lumbering, predictable and sentimental, is worth two hours of your life, if only to ponder the arc of Nelson Mandela’s political and personal life.

The most notable line in the movie comes when Mandela, played by Morgan Freeman, invites François Pienaarthe, captain of South Africa’s ahe all-white-but-one, apartheid-symbolizing, Afrikaner-elite Springbok rugby team, to meet him in the presidential office.

The most notable line in the movie comes when Mandela, played by Morgan Freeman, invites François Pienaarthe, captain of South Africa’s ahe all-white-but-one, apartheid-symbolizing, Afrikaner-elite Springbok rugby team, to meet him in the presidential office.

‘Madiba,’ as his admirers call him, has a political masterstroke in mind. Walking the tightrope of “balancing black aspirations with white fears,” Mandela hopes to unify the re-minted South African nation through the Rugby World Cup, which was held in Johannesburg in 1995.

“How do we inspire ourselves to greatness, when nothing less will do?” Mandela asks the Pienaarthe character, played by Matt Damon.

Despite 27 years in confinement, and use of violence in the anti-apartheid struggle, Mandela spoke of forgiveness toward one’s enemies. He talked about what sustained him during his imprisonment. It was, improbably, the Victorian era poem “Invictus,” whose lines “helped me to stand when all I wanted to do was lie down.”

Mandela thus stirred the Springboks to achieve much more than they thought they could, temporarily unifying the country. The Springboks weren’t expected to even make the quarterfinals, yet beat a team in the finals that stood in a class by itself, the ironically named New Zealand All Blacks.

Anyone who has asked, or is asking, whether there is anything but darkness operating in one’s life, and in this world, feels to some degree what Nelson Mandela felt year after year in that tiny cell. “Out of the night that covers me, black as the pit from pole to pole, I thank whatever gods may be, for my unconquerable soul.”

Just before another World Cup in South Africa, in 2010, and Madiba’s highly anticipated arrival for the opening ceremonies, his beloved great-granddaughter, Zenani Mandela, who had just celebrated her 13th birthday, was killed in a car accident. Even those who steadfastly believe that nothing more than “the bludgeonings of chance” are the cause of this latest, most inexplicable blow to Madiba, are struck by the cosmic unfairness of that death.

A little background that you won’t hear in the rush to canonize Nelson Mandela since his death. He felt a deep debt of gratitude toward Castro’s Cuba, since it was instrumental in defeating the attempt by the CIA and apartheid  government of South Africa to bring down the new Angolan government in the mid-‘70’s. Their defeat in the late ‘80’s drove a key nail into apartheid.

government of South Africa to bring down the new Angolan government in the mid-‘70’s. Their defeat in the late ‘80’s drove a key nail into apartheid.

More recently, as George Bush Junior prepared to invade Iraq, Mandela made this famous statement: “What I am condemning is that one power, with a president who has no foresight, who cannot think properly, is now wanting to plunge the world into a holocaust.” (Bush, who still has no shame about invading Iraq, will be attending Mandela’s funeral with President Obama.)

Mandela also said, “If there is a country that has committed unspeakable atrocities in the world, it is the United States of America. They don’t care.”

But even in the United States, where Mandela’s allegiances and alliances, not to mention some of his Marxist statements, had previously been controversial, the greatness of the man is undisputed.

Madiba wasn’t able to initiate a process to redress the deep economic divide in South Africa however, where the gap between rich and poor, essentially along racial lines, is as wide as anywhere in the world, and crime and violence have exploded in recent years.

Nor has his creation of “The Elders,” a consultative body made up of such notables as Desmond Tutu, Kofi Annan, Gro Harlem Brundtland, Jimmy Carter, Li Zhaoxing, Mary Robinson, and Muhammad Yunus, been able to make a difference in the trajectory of the human crisis, despite “offering their collective influence and experience to support peace building, to address major causes of human suffering and promote the shared interests of humanity.”

However well intentioned and experienced these elders may be, radical change will not come from the above, but from below; not from the old, but from the young; not from political and religious leaders, but from ordinary people reaching for greatness.

Mandela’s canonization is ironic, since South Africa now has become “an anti-black white supremacist country managed by the A.N.C. in the interests of white people,” in the words of one its leading activist organizations, September National Imbizo. For Mandela, forgiveness through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was another political masterstroke, but it did not signify a revolution in thinking and feeling.

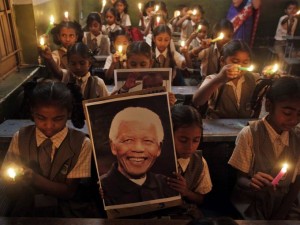

Mandela became an icon of the struggle against apartheid during his imprisonment, and an icon of statesmanship after his release. Icon means “the image of a holy person,” which he was not, and resented being cast. Let’s hope the overused and meaningless word ‘iconic’ is never applied to him.

Whatever happens now at the geo-political level, as the world continues to shrink and darken, we would all do well to take to heart the closing lines of “Invictus,” which sustained Madiba all those years in prison: “It matters not how strait the gate, how charged with punishments the scroll, I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul.”

Martin LeFevre