There’s a great deal of confusion surrounding the idea of limits and limitations, including by supposed philosophers. What are limits, and what are our limitations? It’s a question well worth exploring, since our continued growth as individuals largely depends on our understanding of the issue.

Limits, to my mind, are the present boundaries of our potential as individuals and human beings. As such, limits can and must be tested and stretched.

Limits, to my mind, are the present boundaries of our potential as individuals and human beings. As such, limits can and must be tested and stretched.

Limitations, on the other hand, are the inherent conditions of the flesh—a finite lifespan; a body susceptible to disease and accident; the unavoidability of mistakes; the inevitability of death.

Limitedness however, is an ideological framework and constraint, stemming from fixed ideas about (as opposed to fluid insights into) the human condition.

In short, there are human limitations of lifespan and capacity, and non-fixed limits imposed by circumstance and culture. But ideological limitedness is false, pernicious and harmful to human beings and the human prospect.

To be aware of one’s present limits, and to accept some received idea of human limitation, are two very different things. We grow as human beings by reaching beyond our present and prior limits, not by living within a self-imposed prison of human limitedness.

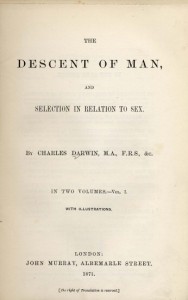

In 1869, Charles Darwin published “The Descent of Man.” In 1973, the BBC aired a documentary written and narrated by Jacob Bronowski, which inverted the title. It was called, “The Ascent of Man.” Even as a young man, I knew the idea of man’s ‘ascent’ was wrongheaded, but I watched as much of Bronowski’s overwrought intellectualizing as I could.

As anyone who looks and thinks can see, Darwin’s title, “The Descent of Man,” not Bronowski’s, “The Ascent of Man,” turned out to be correct. Of course, Darwin was referring merely to the evolutionary line, whereas Bronowski, who died 40 years ago, believed in the gradual improvement of the human species through knowledge. In the series, he often threw a bone to the fact that knowledge is never complete, but he was a leading proponent of the old idea of ‘cultural evolution.’ That’s a dog that won’t hunt anymore.

The central idea of humankind’s upward movement, the climb from ‘the origins of human life in the Rift Valley to the shifts from hunter/gatherer societies, to nomadism and then settlement and civilization, from agriculture and metallurgy to the rise and fall of empires: Assyria, Egypt, Rome,’ is preposterous, yet few people, even supposed thinkers, can let go of it.

shifts from hunter/gatherer societies, to nomadism and then settlement and civilization, from agriculture and metallurgy to the rise and fall of empires: Assyria, Egypt, Rome,’ is preposterous, yet few people, even supposed thinkers, can let go of it.

Man’s descent has been precipitous in the last quarter century, more than 150 years since Darwin wrote is treatise on natural selection. But most academic philosophers still accept the false notion that humankind is ascending, gradually progressing toward a more perfect species.

People who are at all aware and decent share an emotional perception of the fact that the ancient soil of human culture and character is being eroded in inverse proportion to the gains in science and technology. Rather than despairing over it however, that realization drives our transmutation, as individuals and a species.

Ultimately, the notion of “The Ascent of Man” is a romantic ideal, not even suitable to the imaginations of 13-year-old boys. Bronowski does not lessen the romanticism, but merely gives it a macabre twist, when at the end of the series he stands in the muck of man’s past (man as a species, not as gender), and symbolically squeezes between his fingers the ashes of the gassed and cremated remains of people at Auschwitz.

The Nazis did not exterminate 11 million people, including 6 million Jews, because they ‘aspired to the knowledge of the gods,’ but because they believed in the purity of their race and nation. They looked to the past, to resurrecting a bygone era, certainly not to the future of humanity.

Indeed, Nazis regime did not aspire to anything but conquest and Aryan resurrection, and that twisted vision gave the German people of the 1930’s an escape from the misery of their social, psychological and economic conditions. That is the lesson, but it has not been learned, and the West is in danger of repeating it when so-called philosophers continue to promote claptrap about the ascent of man.

Besides, falling back on Hitlerian and Holocaust tropes is the mark of a desperate, mediocre mind, grasping for validation of a failed philosophy of knowledge and progress in the cesspools of human consciousness.

Besides, falling back on Hitlerian and Holocaust tropes is the mark of a desperate, mediocre mind, grasping for validation of a failed philosophy of knowledge and progress in the cesspools of human consciousness.

Equating the quest for clarity, and the confidence that comes with insight, with the false certainty of fundamentalism and fascism is intellectually dishonest and morally repugnant. Such a view feigns humility while actually taking pride in its own false certainties about human nature, preaching tolerance for human limitation while actually resigning to human error.

The juvenile bromide of living in ‘the gray area of negotiation and approximation’ is a prescription for the continued stagnation and stultification of the individual, and prevents us from meeting the crisis of human consciousness that we are all facing.

The human being does not ‘aspire to the knowledge of the gods,’ but to the understanding of the gods. The gods, whatever they are and wherever they dwell, are human beings who have attained an abiding state of understanding and compassion. Therefore, rather than resign to the supposed limitedness of our understanding, our first responsibility as human beings is to aspire to such understanding, for in it is our liberation as human beings.

This quest for clarity is not driven by the desire for perfect knowledge, much less ‘the principle of monstrous certainty.’ Insight and understanding don’t flow from and aren’t functions of knowledge at all.

The greatest human limit is psychological time. But not even that is a given, an immutable prime factor of the human condition, as the advocates of human limitedness believe.

We all have the capacity to end the movement of psychological time in the brain, if only for a short timeless period each day. By allowing the space for the spadework of undivided attention to the entire movement of thought and emotion in the mirror of nature, the brain finds nourishment and renewal in the ending of psychological time.

Martin LeFevre