Sometimes what people call meditation is as far from my understanding of it as a jihadist’s idea of heaven. It sounds more like the continuity of hell to me. Central to meditation is communion with death as an ever-present actuality. For some Buddhists however, death is a detestable riddle.

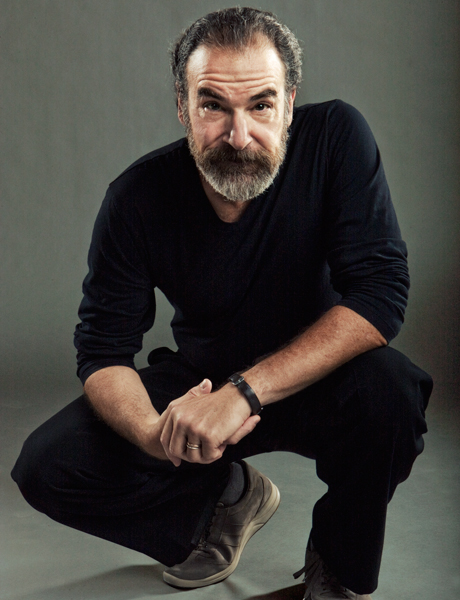

I heard a riveting interview recently, conducted by the ubiquitous Charlie Rose with the actor Mandy Patinkin, who calls himself a ‘Jew-Bu,’ short for Jewish Buddhist. Patinkin said he had “just lost the dearest person in my life, my cousin Marvin,” and there was a raw, emotional, and near-tearful quality to the entire interview.

I heard a riveting interview recently, conducted by the ubiquitous Charlie Rose with the actor Mandy Patinkin, who calls himself a ‘Jew-Bu,’ short for Jewish Buddhist. Patinkin said he had “just lost the dearest person in my life, my cousin Marvin,” and there was a raw, emotional, and near-tearful quality to the entire interview.

He became angrily passionate and sadly revealing after speaking about how he had taken a 25-hour flight to see Marvin before he died, only to learn when he arrived that his cousin had died an hour before.

With a fervor filled with hurt and rage, he almost shouted: “I’m not a fan of death. You know in Buddhism they say, ‘embrace suffering, be aware of it, learn to let go.’ To hell with it! I hate death. I hate it. I think it’s the true flaw in the whole system.”

At that point Charlie Rose interjected, superciliously, “You mean, as Dylan Thomas said, ‘Rage, rage, rage?’” He added a third ‘rage,’ and didn’t complete the line, “against the dying of the light.” Mandy was on such a high-speed emotional train that he didn’t even register the non sequitur, but went on speaking about death. “What’s good about it? Why shouldn’t you get to be here forever?”

There was great sorrow in Patinkin’s short speech. Not just because he’s suffering from the death of a loved one, but also because he’s suffering from a total lack of understanding of death.

I still grapple with fear, sorrow and dejection, but one thing I’m unshakably sure of—the validity of experiencing life and death inseparably, and the potential in every human being for communion with the ground of life, which is death.

Beyond the word, beyond the cycles of birth and death, the infinite ground is present. Before this universe was born, death was there as the silent ground.

Science can never gain knowledge about death, because the ground of death precedes all energy, matter and information. Death is the ending of all continuity, and beginning of all things.

So what do we fear? And what does Mandy Patinkin hate when he says he hates death? It isn’t the actuality of death, but the thought and fear of it, specifically the subconscious realization that death is the end of the continuity of ‘me.’ Therefore the answer to Mandy’s question, “why shouldn’t you get to be here forever?” is because that goes against life, which cannot be divided from death.

What some call the ‘attainment of unity with the Divine Mind and the Divine Will’ is only possible, in life, by making a friend of death, and entering its house every day.

That’s the great paradox of life. Sometimes a paradox is simply a contradiction. But in this case, we intellectually know but don’t emotionally experience: Life and death is a single movement. The contradiction and conflict between life and death is a product of the human mind.

If life and death are a single movement, why do we divide off and hold death away from life? Because thought and self are  continuity, and death means their end. The insight that death is not just part of life but is the ground of life begins to address and dissolve our primal fear.

continuity, and death means their end. The insight that death is not just part of life but is the ground of life begins to address and dissolve our primal fear.

But what does ‘entering the house of death’ mean? It sounds terribly morbid.

In true meditation, when there’s spontaneous stillness, there is “a flowering without roots and so a dying.” The ‘me,’ which is the continuity of the core program of thought in the brain, ends, if only temporarily. That is what makes the question, “why shouldn’t you get to be here forever?” so misguided. Meditation is the ending of all continuity, and a rebirth in the ending.

When there is a daily ending by entering the house of death without fear or morbidity, life is perpetually beginning. Meditation goes beyond awareness of death to the experiencing of death while fully alive. Such states are completely timeless, and embody the highest states of being.

One of the most common clichés these days is ‘life is good.’ In the best sense, which is the rarest usage, it means, ‘the world is crazy dark, but life is still good.’ More often, it’s a form of ultimate denial, conflating the world with life, and declaring both good. As such it fails to make the distinction that a ten-year-old can make, if she has any real teachers.

Sometimes, in the most cunning people, there’s a darker message. What they are surreptitiously saying is, ‘you’re being negative,’ while they are taking the ‘positive’ view that ‘life is good.’ Of course they don’t want their worldview examined, so they try to undermine rather than bring forth for examination how they see things.

Truly, life and death are good. Or, more accurately, the movement of life and death is good.

Martin LeFevre