A magnificent hawk—perhaps an eagle—circled three times high above the stream. Shortly thereafter, a ‘kite’ appeared, fluttering in the distance over the fields to the north, barely visible through the bare trees.

Suddenly it reappeared without obstruction, much closer. The gentle falcon held its position like a flickering candle, opening a dimension of grace through which one instantly felt the nameless awareness of the numinous.

Suddenly it reappeared without obstruction, much closer. The gentle falcon held its position like a flickering candle, opening a dimension of grace through which one instantly felt the nameless awareness of the numinous.

Three junior high girls, full of life and laughter, came down the path toward the creek. The lead one waved and they went the other way, downstream. A few minutes later they walked up, garrulous with each other but not speaking to me until I did to them.

In a friendly way, I asked, what are you girls doin’? “Nothin’, we’re on an adventure,” the ringleader said, clearly in charge of the outing. I asked if they attended the nearby junior high, and again, only one spoke. “They do,” she said, adding that she attended another school across town.

When I stood up to stretch and walk along the bank, they were frolicking about on the paved bike path about 75 meters away. A kite, probably the same one, was just behind them, hovering in place. The sight of the slender raptor floating above the girls was a moment out of time. They didn’t see it, so I pointed and they turned around. ‘A falcon,’ I shouted. “Really?” one of them said.

From the sublime to the malevolent, I read today where the Right Reverend William E. Swing of San Francisco, founder and president of the United Religions Initiative, visited Jordon right after Islamic terrorists immolated the caged Jordanian pilot. He asks, “What is the solution to religion in that region, which, so often, boils into bloodletting?”

It’s the wrong question. The right question is, “What is the solution to religion?” Full stop.

The first mistake is always the unseen one. In this case, the implicit superiority of pointing to “that region, which so often boils into bloodletting,” while refusing to see the denuded inner landscape religion has wrought in North America.

With respect to America, never have so many people belonged to so many religions but been in actuality so irreligious.

I don’t mean irreligious in the sense of not adhering to the Judeo-Christian moral code, or to the brutal conservative ideology of virtue. Rather, virtue in the sense that Socrates used the word, which he defined as order in consciousness. From that order comes fellow feeling, kindness, and a feeling of humility and reverence.

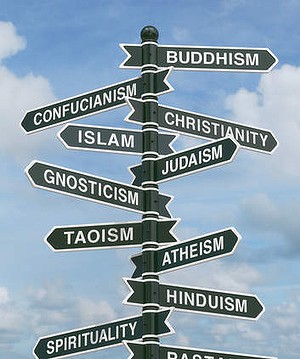

Swing says, “There is no such thing as religion, singular. But there are always religions, plural and in competition.” Yes, and that’s precisely the problem.

Not that there can or should be just one religion, singular. Rather, the religious mind holds the question, without answering it definitively: Is there something beyond all these jejune spiritual expressions,  murderous belief systems and putatively holy texts?

murderous belief systems and putatively holy texts?

The Rt. Rev. Swing proclaims, “This is the religious test: respect the children of other gods.” The lower cap is his; he does not say, “children of other Gods.” Yet that is the way all true believers see it, as absurd as it is, and why pluralism skates on the surface of the infernal manifestation called the world.

The difference between belief and spirituality has become a chasm of meaning for many people, as wide as the distinction between science and religion.

To the spiritual person, evolution is a given, a source of mystery and wonder in itself. But a believer in orthodox Christianity has to be an intellectual contortionist to also embrace the discoveries of science, beginning (ahem) with evolution.

Even so, we can ask, what does it mean to be religious, whether one belongs to a community of believers in a particular faith or not?

There is an experiencing of essence that springs from and reaches beneath all these different forms and expressions, which at best are cultural idiosyncrasies, at worst (as they’re presently playing out) the most virulent sources of division, conflict and violence.

Doctrinaire atheism—the belief in reason and nothing but reason—throws the baby (the infinite mystery of life and the possibility of experiencing the numinous) out with the bathwater (decaying belief systems, deracinated rituals, delimiting scriptures and demarcated ‘houses of worship’). But even atheists are now forming their own ‘churches.’

After survival requirements, religion in the deeper sense, synonymous with spirituality, is the first and most foundational drive of human beings. Religion in the universal meaning of the word is closely followed, and goes hand in hand with philosophy in the true sense—the love of truth.

The problem with ‘interfaith dialogue’ is that upholds being “children of different Gods.” As such, it presupposes separate spheres of spirituality, and attempts to bridge the chasm between two disconnected camps.

Religions in this view are the spiritual equivalent of nation-states. Assuming sovereignty (that is, the supreme thing) in either sphere has become the deafening death knell of human cooperation.

There is another approach. Rather than inter (between) faith, as in belief, it is intra (within) faith, as in keep the faith. Not within particular belief systems and traditions, but within in the sense of below and beyond all texts and traditions.

Of course that would mean holding one’s own faith lightly, rather than seeing it as ‘the truth,’ and listening for truth as a moment of insight in dialogue as questioning amongst people humbly seeking a deepening, shared understanding.

Only then is can there be such a thing as religion, singular, synonymous with spirituality, plural.

Martin LeFevre