It’s become fashionable to talk about angels, even to proclaim that one is a channel for this or that incorporeal deity. Such stuff rubs me the wrong way, though I don’t dismiss it out of hand. 99% horse pucky still leaves 1% that isn’t.

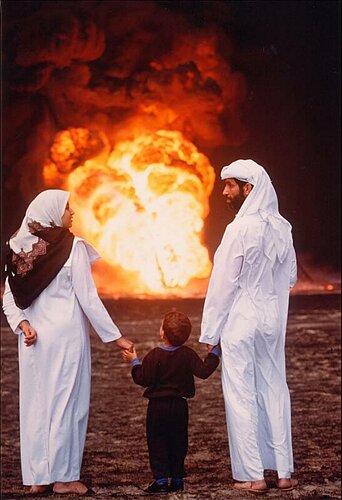

The only time I heard a voice that I was sure didn’t come from own head was right after the first Gulf War. Though I’d seen the war coming for months, and wrote and gave speeches about its inevitability (incurring disapproval from what I thought were like-minded compatriots on the left), I went into a deep funk after America’s glorious victory over Saddam following his invasion of Kuwait, which killed less than 200 of our precious troops to well over 200,000 of his cannon fodder.

The only time I heard a voice that I was sure didn’t come from own head was right after the first Gulf War. Though I’d seen the war coming for months, and wrote and gave speeches about its inevitability (incurring disapproval from what I thought were like-minded compatriots on the left), I went into a deep funk after America’s glorious victory over Saddam following his invasion of Kuwait, which killed less than 200 of our precious troops to well over 200,000 of his cannon fodder.

The funk wasn’t personal. It wasn’t even despondency, much less depression. It was a condition I couldn’t name, with a cause I couldn’t see.

I was living in Silicon Valley at the time and would meditate and walk in the hills above South San Francisco Bay whenever I could get out of the high-tech hecticness that pervades the Santa Clara Valley now as it did then, in the early ‘90’s.

For weeks after the war, I couldn’t shake a feeling that something essential had changed, but I didn’t know what. I kept asking, ‘what is this feeling?’ Meditation had become more consistent at the time, and I would take short sittings before a brisk walk in the hills above the bay a few times a week.

One day, after an especially intense meditation in which the mind fell completely silent, I again asked the question that had plagued me since the end of Bush Senior’s war—what is this feeling?

A voice reverberated in the silence of the mind. It had a hint of exasperation, or at least obviousness: “You’re in mourning,” is all is said.

“That’s it! I exclaimed as one who suddenly discovers what’s ailing him, with the relief that doesn’t care where the answer came from. The instantaneous next question was equally obvious in retrospect: What am I mourning? “You’re mourning the death of your nation’s soul,” came the emphatic response.

The shock of realization, the unshakable factuality of it, remains with me to this day. The ensuing years, from the LA riots to 9.11, from OJ’s mockery of justice to Barack’s promise and disappointment, have confirmed the simple truth again and again. But denial still rules the land.

I don’t know where the voice came from, only that it in the stillness of thought in a meditative state, it didn’t come from my own head. And I don’t care whether anyone else believes it, only that the denial ends, since the deadness is spreading around the world.

Even Dutch authors, writing about the national mourning that has overtaken that country after the MH17  tragedy, in which half of the people that fell “like clumps of dust” out of the sky were from the Netherlands, advocate becoming numb as a response to the world. The deadness that began in America has gone global. Adapting to a dead culture, one becomes dead oneself. That’s why movies like Brad Pitt’s “World War Z,” depicting zombies overrunning the world, are so popular.

tragedy, in which half of the people that fell “like clumps of dust” out of the sky were from the Netherlands, advocate becoming numb as a response to the world. The deadness that began in America has gone global. Adapting to a dead culture, one becomes dead oneself. That’s why movies like Brad Pitt’s “World War Z,” depicting zombies overrunning the world, are so popular.

“The whole world puts a claim on our feelings, from the lady next door to our family members and the panhandler on the street, from the news about Gaza and on to Ukraine, from Congo to Syria. Our emotions are constantly being claimed,” writes Arnon Grunberg in the New York Times.

“That these claims have a numbing effect on us, that we are often indifferent, that we are busy enough as it is trying to provide emotional succor for those closest to us, and often don’t even succeed in doing that, seems to me not so much a sign of our inhumanity, but of our humanity. Were we to actually allow the world’s suffering to sink in, we would quickly become psychiatric cases, lulled by the power of psychotropic medications into a state of detachment.”

So becoming numb, which basically means not feeling what we feel, is a sign of our humanity? That’s a very perverse definition of humanity. No, the deliberate refusal to feel what we feel is the worst human failing. We shrink as human beings in direct proportion to the degree that we cut off our capacity to emotionally respond to what is going on next door, literally and metaphorically.

The idea that we have only so much capacity to feel, and that have to delimit what our hearts can hold or our heads will descend into madness, is not only completely mistaken, it’s malevolent.

Grunberg goes on to say, “I recognize the tragedy, I realize that you are mourning, but I can’t mourn along with you, not right now.”

The words “right now,” whether they come out of a friend’s mouth or one’s own, are an emotional and spiritual red flag. They are existentially dishonest, indicating a concern only for the immediate, for what pertains to me. They tell of the toxicity of our times, spreading it in a seemingly innocuous phrase and frame of mind.

Many people in the West are on psychotropic drugs not because they feel too much but because they feel too little. The most painful feeling of all is to not feel anything, and the psychiatric industry has been only too willing to provide drugs on an industrial scale to make the flattening of feeling (A K A depression) tolerable.

Detachment is necessary and healthy; indifference is unnecessary and hateful.

Martin LeFevre