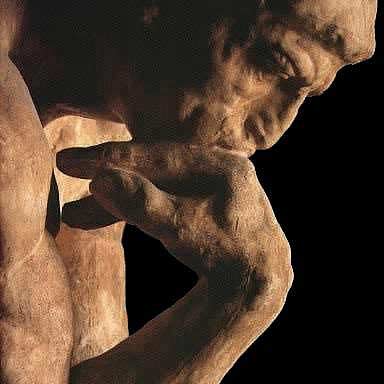

“Ignorance is not lack of knowledge but of self-knowing.” I read that provocative statement today, and it prompted these questions: What is self-knowing? What is the difference between self-knowing and self-knowledge? Why is it essential to be self-knowing?

The core feeling of the self-knowing person is ‘I don’t know.’ Asking someone whether they are self-knowing is like asking whether they’re a good person. The most anyone can say is ‘I value being a good person, and pursue self-knowing as a means without end to being one.’

The core feeling of the self-knowing person is ‘I don’t know.’ Asking someone whether they are self-knowing is like asking whether they’re a good person. The most anyone can say is ‘I value being a good person, and pursue self-knowing as a means without end to being one.’

Being self-knowing means looking at oneself afresh every day, almost as if one is a stranger you’re meeting for the first time. It is seeing and remaining with what is within oneself as it presents itself in the moment—what one is actually thinking, feeling and doing—without judgment, direction or analysis.

A self-knowing person makes the distinction between what they think and what is. They have the intent to simply see what is, even and especially if it’s something disturbing, like hate, jealousy or fear. The human tendency is to act from what we think is, rather than from seeing and understanding what is. That mistake is encouraged in a culture that constantly beats the drum of positive thinking, which is the most negative thing.

So to be self-knowing one has to be skeptical of what one actually thinks and feels. Doing so leads to understanding of oneself and others, as well as the world and human consciousness.

As I practice it, self-knowing applies mainly to meditation, but it also applies to being mindful of oneself in relationship with one’s friends and family.

The current, party-line interpretation of the teaching of self-knowing refers solely to being mindful of oneself in relationship. That idea has degenerated into solipsism, the view that the self is all that can be known to exist. ‘All I can know is myself,’ solipsists say. Or more subtly, ‘I have to begin with myself.’

That sounds reasonable, even undeniable, and it’s very persuasive, especially in an individualistic culture like America’s. However if one listens to the subtext, the center is still assumed and strengthened, and self-centeredness is left untouched.

Is that why egocentrism has increased since the group meditation wave has swept over the land? Is that why despite the influence of Buddhism, nothing has changed in the last 20 years, and the culture has grown much darker, and actual relationship more rare?

No doubt there are many causes of the erosion of character in North America. The question before us is, can people turn within without becoming  more self-centered, and feeding the narcissism that has become so rampant?

more self-centered, and feeding the narcissism that has become so rampant?

There is looking without a center, and learning without accumulation. But there’s inevitably a center when there is accumulation of experience, stored in memory. Self-knowing is not additive. It isn’t a matter of knowledge in any form.

Psychological and spiritual learning is always of the present. Memory, association and prior experience play no part in it.

The irony is that most think they control their actions when in fact conditioning, the culture and forces in collective consciousness of which they are wholly unaware control them.

The paradox is that when there is an observer, there cannot be self-knowing. The observer gives the illusion of standing apart and choosing, but it’s actually inextricably part of the background of thought and emotion. It’s merely a program, a filter of judgment and choice. And inward learning and growth are denied when there is the illusion of choosing and directing one’s thoughts and emotions.

Without self-knowing, the brain accumulates experience, the content of which forms the basis of our actions. Experience is highly valued, when in fact it has no value psychologically and spiritually. Has a ten thousand years of experience made man less divided, less prone to fragmentation and destructiveness? Knowledge and experience apply only to the scientific and technological realm, not to the psychological and social dimension.

Without self-knowing attention, the brain acts like a sponge, accumulating the detritus of experience. Meditative self-knowing initiates the movement of negation, which effortlessly squeezes the dirty water of experience from the brain, allowing the cells and neurons to be clear and clean again.

Sitting quietly for 20 minutes every day and without direction or choice watching the movement of thought and emotion (the past), the mind naturally goes into meditation. It comes upon emptiness and nothingness without fear or reaction. In emptiness and nothingness, without words and images, there is awakening, insight and freedom.

Then, when one isn’t looking for it, or for anything, something completely beyond words comes, a benediction.

Martin LeFevre