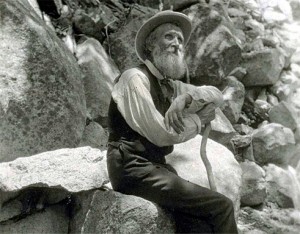

Backpacking in the Hetch Hetchy wilderness, you feel both its vastness and sublimity, and a heartbreaking truncation. Magnificent waterfalls plunge over the cliffs, only to fall into a huge reservoir. To John Muir, one of the greatest American voices and the father of the modern environmental movement, the Hetch Hetchy Valley rivaled Yosemite Valley in grandeur.

The losing battle to save Hetch Hetchy broke Muir’s heart and cut short his life. Though there were alternatives then as now, in the early part of the 20th century the economic pressure to build a dam and fill the valley with water for San Francisco’s population and power was just too strong. How much stronger is it now with respect to the earth as a whole?

The losing battle to save Hetch Hetchy broke Muir’s heart and cut short his life. Though there were alternatives then as now, in the early part of the 20th century the economic pressure to build a dam and fill the valley with water for San Francisco’s population and power was just too strong. How much stronger is it now with respect to the earth as a whole?

The fight to save Hetch Hetchy lasted ten years, beginning under Teddy Roosevelt and ending with Woodrow Wilson signing Valley’s, and John Muir’s, death warrant in 1913. “Dam Hetch Hetchy!” Muir famously said, ”As well dam for water-tanks the peoples’ cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has been consecrated by the heart of man!”

Now, a hundred years later, one of the greatest fires in California’s history, the Rim Fire, which is still burning but mostly contained, has threatened the dam and reservoir at Hetch Hetchy. San Franciscans may well taste ashes in their famously pure water next year. Will it remind them of John Muir, and kindle the cri de coeur: Tear Down This Dam!

That Hetch Hetchy Valley was as beautiful as Yosemite Valley is hard to imagine for anyone who has ever visited Yosemite. Upon first beholding the Valley, Half Dome, El Capitan and Bridal Veil Falls so deeply imprint themselves on your mind and heart that one may mark one’s life as before seeing Yosemite Valley and after.

The High Sierra, and Yosemite in particular, certainly affected a flatlander from the Midwest that way. My ignorance of the mountains that John Muir called “The Range of Light” was so great that when a friend called after my sophomore year to ask if I wanted to spend the summer working in a camp for speech and deaf kids near Sequoia National Park, I thought they were called the Sahara Nevada.

Returning to live in California, I hiked in the High Sierras as a young man, and soon understood why Muir loved these mountains so much. As he said:

“After ten years spent in the heart of it, rejoicing and wondering, bathing in its glorious floods of light, seeing the sunbursts of morning among the icy peaks, the noonday radiance on the trees and rocks and snow, the flush of the alpenglow, and a thousand dashing waterfalls with their marvelous abundance of irised spray, it still seems to me above all others the Range of Light, the most divinely beautiful of all the mountain-chains I have ever seen.”

The Sierras, Muir added, “were throbbing and pulsing with the heartbeats of God.”

My Hetch Hetchy trip is memorable for the searing contrast between nature’s beauty and man’s ugliness, as well as the difficulties and dangers my friend and I faced.

difficulties and dangers my friend and I faced.

We started in late spring with cross-country skis strapped to our backpacks, prepared for the snow we knew we would encounter once we got above the dam and reservoir.

As we traversed one steep slope on skis, a thunderstorm came up. Already spooked because of the possibility of avalanche, we grew nervous as the storm grew closer. It proved to be one of those come-home-to-Jesus moments.

Thunderstorms are to Californians as rattlesnakes are to Michiganders—fearsome forces of nature that are usually more terrible in mind than in actuality— unless one bites you. You learn, living near the big lakes, when a thunderstorm is dangerous and when you just need to be wary. Californians learn that as long as you don’t step on a rattler, or corner one, they almost certainly won’t strike.

My friend hadn’t seen many thunderstorms, as I hadn’t seen many rattlers. As the storm intensified around us, his pace on his skis quickened in front of me. Truth be told, I also grew afraid as lightening and thunder came in quick succession, indicating the storm was nearly overhead. Suddenly, panic overtook him, and he bolted for the trees, about a mile away. I never saw someone move so fast with a backpack.

He said later he thought he would never see his children again. Perhaps my not having any children contributed to the strange acceptance that came over me. I felt, if I’m going to be hit, there’s nothing I can do about it.

When I got to the tree he stood under, I said, ‘you know, we aren’t any safer here than we were on the slope.’ But the storm passed quickly, as did the rest of the difficult but astoundingly beautiful trip. A scene looking down on an aquamarine little lake surrounded by snow was so beautiful that it brought tears to my eyes, and is imprinted on my heart forever.

San Francisco city officials are putting out the line that residents won’t see or taste any effects from the Rim Fire. Thus  the city where the Sierra Club has its global headquarters refuses to countenance even an inconvenience when it comes to the present threat and future restoration of their precious water quality and power generation.

the city where the Sierra Club has its global headquarters refuses to countenance even an inconvenience when it comes to the present threat and future restoration of their precious water quality and power generation.

The Hetch Hetchy dam was built at the peak of the great continental ravagement, during a century of inexorable expansion and decimation of lands and native peoples that Americans called “Manifest Destiny.”

“The great wilds of our country, once held to be boundless and inexhaustible, are being rapidly invaded and overrun in every direction, and everything destructible in them is being destroyed,” Muir said.

Speaking of the Giant Sequoias, some of which were threatened by the Rim Fire, Muir said, “Through all the wonderful, eventful centuries since Christ’s time, and long before that, God has cared for these trees, saved them from drought, disease, avalanches and a thousand straining, leveling tempests and floods. But he cannot save them from fools.

Any fool can destroy trees; they cannot run away. If they could, they would still be destroyed, chased and hunted down as long as fun or a dollar could be got out of their bark hides.”

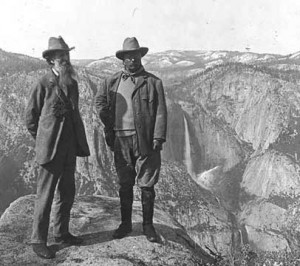

President Teddy Roosevelt camped with Muir for three nights in the High Sierra above Yosemite Valley, one night under the Giant Sequoias. “This has been the grandest day of my life,” TR said when he reached the Valley on horseback.

During one of their long talks well into the night, Muir pointedly asked the indomitable TR: “Mr. President, when are you going to get over this infantile need you have to kill animals?” Can you imagine that? (What’s left of the American spirit must rise up and say to President Obama this week: Mr. President, when is America going to get over this infantile need to unilaterally intervene and invade other countries?)

During the 19th century the Census Bureau literally drew a line against wilderness, calling it “The Frontier Line.” It demarcated the continent with the motto, “Redeemed from wilderness by the hand of man.”

For Muir of course, man was redeemed by wilderness. As the writer Gretel Ehrlich said, “I think John Muir understood, as perhaps no one else has, how essential natural beauty is to us. Without beauty we have no lubrication of the human spirit; we would just be dead.”

Now man stands on the verge of plundering the entire earth for all successive generations. We, the living generations, face the greatest choice in the history of our species short tenure on this precious planet.

We will either change ourselves at the root, and save what is left of the wild diversity of animals and plants, mountains and seas, or leave ashes to our children and their children on down to our own likely extinction. Can people change? Yes, we can.

Martin LeFevre

Sources and links:

http://www.hetchhetchy.org/

http://www.pbs.org/nationalparks/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/O’Shaughnessy_Dam_(California)