In the not very distant past—decades, not centuries ago—there was space on the earth for man to make his primeval mistakes of separation, division and rapaciousness. The question of the fate of humanity wasn’t pressing, as it is now.

In our age however, both our success and failure as a sentient species (and it can be difficult to discern which is which) man has used up the formerly vast spaces of the earth.

In our age however, both our success and failure as a sentient species (and it can be difficult to discern which is which) man has used up the formerly vast spaces of the earth.

In directly proportion, our inward horizons have shrunk, shrunken to the point that many young people don’t even know what they are missing.

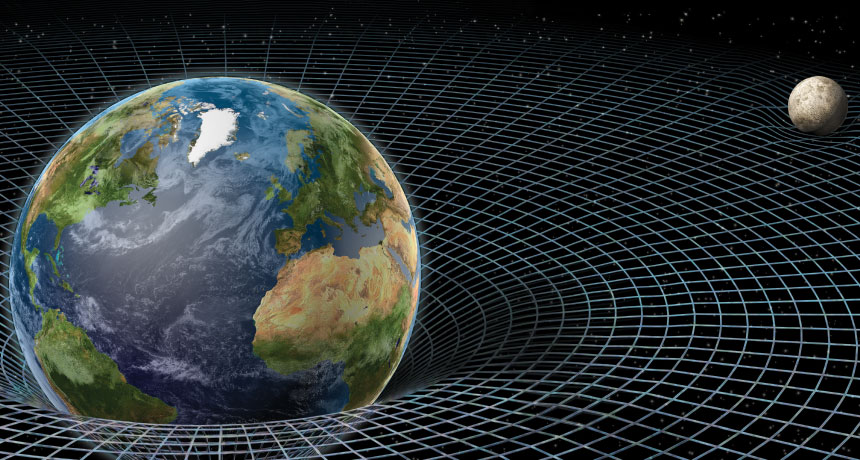

The question of space is inextricably the question of time. Earthly space-time in turn is directly related to the actuality of limits.

Astoundingly, I’ve found that many young people have no sense of limits. They think and act as if humans have all the space and time in the world, and that if we destroy the earth and ourselves it doesn’t matter anyway.

My smart and successful 20-something nephew wrote me recently: “There’s nothing but time because even if we humans don’t make it, something will, whether it be alien life, or AI, or life re-evolving after we are gone.”

To my mind and heart, this is a deeply disturbing, false optimism. Unfortunately, many young people, following the movers and shakers in the tech world, embrace such a worldview.

My nephew went further in his apologia for human destructiveness. On one hand, he denied there are limits to human destructiveness; on the other hand, he dismissed limits as unimportant. Finally, he affirmed the Western belief in technological fixes. It was a neat intellectual hat trick.

His deceased father and I were born a few weeks apart, and grew up together in the same town as first cousins. Though my cousin didn’t feel, as I do, that there’s a spiritual meaning and purpose to the evolution of brains such as ours in the universe, I know that he would recoil from such a laissez faire attitude toward the human crisis.

“Something stupid like another asteroid could take us out, but given the progress of the last 200 years…I’m optimistic. Colonize Mars, get it done.”

That last line haunts me: “Colonize Mars, get it done.” There’s an admixture of denial, resignation, hubris and despair in it.

The denial is of the self-made human crisis, which is projected outward onto impersonal forces of the universe. So the resignation and despair are not with respect to an asteroid or some other dinosaur-killing natural disaster, but toward the human prospect itself.

The hubris is in the lack of any limits on human progress, with the belief that if we devastate our home planet, we can just colonize Mars and other worlds. If there is any such thing as justice in the universe, colonizing Mars while destroying Earth is not an option.

The idea that artificial intelligence—machines made in the image of thought—will be the next step in our species’ supposed evolutionary progress is a fantasy promoted by such tech heavyweights as Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos. It’s a dangerous pipe dream.

AI, without the intelligence (that is, wisdom) to use it fittingly and harmoniously, will only increase human dependency and stupidity. I feel there is a universal law: The inwardly generated crisis that a sentient species generates cannot be resolved in an externalized, technological way.

As to whether alien life will make it if we don’t, how could that be? Clearly on each habitable planet where conditions for life are stable enough to evolve technological, potentially self-knowing creatures, each has to resolve its own contradiction with nature on its planet, which the evolution of  ‘higher thought’ ineluctably produces to one degree or another. (I nominate my own species as the most pigheaded, potentially intelligent species in this galaxy.)

‘higher thought’ ineluctably produces to one degree or another. (I nominate my own species as the most pigheaded, potentially intelligent species in this galaxy.)

Stephen Hawking’s frets that because humans have been tribally aggressive, with one group dominating another throughout history, we should fear alien life, because aliens would be tribalistic and tyrannical as well. Frankly, that’s spiritually and philosophically juvenile.

I still don’t understand how my nephew can sanguinely and self-comfortingly maintain, “if we humans don’t make it, aliens or AI or life re-evolving will.”

But such a worldview seems to afford an effective palliative for despair in many people these days. How long can the human species avoid the reality of limits and the urgency of radically changing ourselves?

Just as a meditative state ignited on a wet, windy day, the skies brightened the sun shone directly above the stream. In a moment, the atmosphere changed, and light filled the land, waters and sky.

The beauty was palpable, and reverence came as naturally as the light. As one entered a limitless dimension of being, the world receded into the dim and distant cacophony it actually is.

Once again one felt the peace that passes all understanding. That’s reason enough to meditate, though it’s only the first of its endless gifts.

Martin LeFevre