A young, homeless-looking man is at my sitting spot on the creek when I arrive late in the afternoon. He’s brought his bike down the bank with him, and a motley assortment of things are scattered around it.

He gives a wan wave, and I go back upstream a few hundred meters to the alternate site. As I walk down the path, I see him going the other way carrying an empty 7-up container, heading toward a drinking fountain on the park road. I wonder what his story is.

He gives a wan wave, and I go back upstream a few hundred meters to the alternate site. As I walk down the path, I see him going the other way carrying an empty 7-up container, heading toward a drinking fountain on the park road. I wonder what his story is.

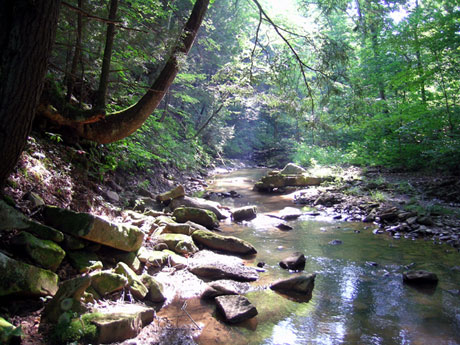

The meditation, which takes place along a more visible, but also more placid section of the stream, begins slowly, as it usually does, with the senses attuning to the sounds, sights and smells in the environment. The smell is of brown grass, dry dirt and a hint of water; the sight is of thick foliage in various hues of green. There’s a large, vine-like tree draping big, heart-shaped leaves over the gentle current.

But it’s the sounds, or rather the lack of man-made noise, that stands out. A soft cascade less than 100 meters upstream is the loudest thing in the aural environment. The silence is only punctuated by snippets of conversation between unseen cyclists passing by behind a hedge of bushes and trees, and by the occasional bark of a dog or the distant roar of an especially loud engine.

Listening as well to the movement of thoughts and emotions as they arise (and with the same quality of non-judgment and non-interference as listening to the creek flowing by), the mind effortlessly quiets, and the heart lets go of even the most painful emotions. One is able to hear the domination of thought in the brain, and the listening alone releases the mind/brain from its bondage to thought.

Freedom doesn’t lie in separation of any kind, even politically, much less individually. Independence as we generally know it has nothing to do with freedom. It has come to mean the illusion of being outwardly, individualistic self-sufficient. Physical dependency on each other is a fact, but few people are willing or able to stand alone inwardly. Freedom is first and last within.

One develops a feeling for when the observer falls away, a proprioception, like knowing where your arm is when you close your eyes. Without making a goal of meditating, or operating from an idea of what it is, the observer ends, and there is simply undivided observation.

I’ve long felt that meditation doesn’t begin until the observer spontaneously ends in passively watching everything outside and inside. Now I feel meditation doesn’t really occur until psychological time ends.

Psychological time is a very subtle thing. It’s concealed in the recesses of thought, taking many forms of cognitive continuity, from  the replay of a conversation earlier in the day, to looking forward to something one is planning on doing tomorrow, to the hidden seeds and needs of becoming. Sorrow and fear are byproducts of the continuity of thought.

the replay of a conversation earlier in the day, to looking forward to something one is planning on doing tomorrow, to the hidden seeds and needs of becoming. Sorrow and fear are byproducts of the continuity of thought.

When time ends all continuity simply stops, without volition, in the act of attending to the movement of what is happening inwardly and outwardly. Even the duality of ‘inwardly and outwardly’ ends, and there is just what is, unfolding in insight and understanding. Eternity is not a function of time.

To me this is what leaving the stream of content-consciousness means. I realize that most people rarely experience that state, which makes me wonder, is it only for very few? That doesn’t make sense.

All one can do is reawaken timeless awareness every day until one leaves the stream irrevocably. Not at death, since even then I don’t think one leaves the stream if one hasn’t left it while alive (not that the self continues after death), but rather in this life, while fully alive.

Starting of my walk after the meditation, I see that the young man is still there. Feeling more gregarious despite the inward silence, I stop and speak to him.

He’s Hispanic and his English is poor. Naturally he thinks I want the place, but I say no, I had my meditation. I ask if that’s what he’s doing here. He doesn’t understand, and it isn’t because of the language barrier. I say a few words about meditation, wish him well and leave. I hope the place, where many tremendous meditations have occurred, leaves him with something.

Near the end of the walk on the park road, dripping with sweat on a hot evening, a woodland hawk swoops in and lands just in front of me. I stop, and though it’s only a few feet away, it doesn’t fly away.

It seems meaningful in some way I don’t understand at the time. The Cooper’s hawk is surprisingly large for a woodland variety, and has striated wings of various shades of brown. It stares at me unblinkingly with intense eyes, and doesn’t move even when two cyclists ride by, talking obliviously.

For nearly ten minutes we look at each other, until the raptor gently drops from its low perch and flies off downstream. I can still feel its eyes, embodying the awareness and mystery of nature itself, and something beyond nature. Don’t look away.

Martin LeFevre