In her famous poem, “The brain is wider than the sky,” Emily Dickinson provides a powerful counter to the premises and presumptions of neuroscience. We would do well to consider this perspective before plunging ahead.

First, let’s be clear about the truly disturbing, even horrifying scenario that supposedly serious people are embracing as a wonderful future for humanity.

First, let’s be clear about the truly disturbing, even horrifying scenario that supposedly serious people are embracing as a wonderful future for humanity.

In “Homo Deus, A Brief History of Tomorrow,” Yuval Noah Harari, writes, “very soon we might be able to break out of the organic realm using things like brain-computer interfaces.”

This, we are supposed to believe, is a good thing. After all, what can possibly go wrong by “replacing natural selection with intelligent design—not the intelligent design of some God above the clouds, but our intelligent design.”

At the core of the dominant scientific/technological worldview with respect to the brain and consciousness is the idea that in building more and more powerful computers, we are duplicating (if not replicating) the essential element of consciousness: memory.

“If you find ways to connect brains and computers, you can rely on memory’s immense databases outside your own brain…to upgrade the healthy brain,” Harari blithely writes.

To anyone with a philosophical brain in his or her heads, the underlying assumptions about consciousness simply don’t wash. Is the brain and consciousness solely or even primarily a function of memory, or for that matter knowledge?

Emily is edifying:

The Brain—is wider than the Sky—

For—put them side by side—

The one the other will contain

With ease—and You—Beside—

To our sophisticated, scientific ears, this sounds oh so quaint and romantic. As with all good poetry however, its meanings lie far beyond the simplicity of its form and words.

What Dickinson is saying becomes clear as one reflects on the rest of the poem:

The Brain is deeper than the sea—

For—hold them Blue to Blue—

The one the other will absorb

As Sponges—Buckets—do—

The Brain is just the weight of God—

For Heft them—Pound for Pound—

And they will differ—if they do—

As Syllable from Sound—

Contrast the interpenetrating insights of this poem with the crude but increasingly plausible future extolled by Harari: “It’s likely that all the upgrades [of brain-computer interfaces], at least at first, will cost a lot and will be available only to a small elite.

To his credit, Harari sounds a cautionary note, albeit one that implicitly and explicitly praises the brave new world science offers us: “We need to start thinking far more seriously about global governance because the only solution to such problems will be on a global level, not on a national level.”

He concludes, “nationalism is far more dangerous because not only it leads to war, it also may prevent us from having any effective answer that can help us cope with dangers like the rise of artificial intelligence or the implications of bioengineering.”

While one commends his perspicacity with regard to the atavism of nationalism, “coping with dangers like the rise of artificial intelligence and bioengineering” demands an equal consideration of the black hole of scientism and technologism into which many putative thinkers are giddily plunging.

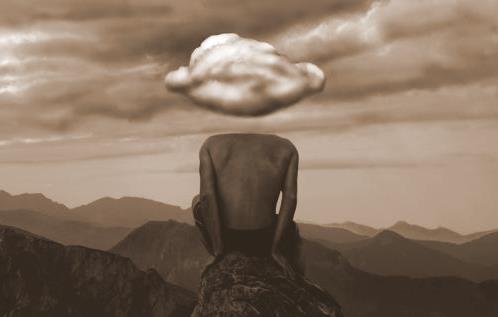

Emily’s list toward life provides a ready tonic. “The Brain is just the weight of God” is a phrase that can and should give frequent pause. The insight Dickinson offers is that the mechanistic, materialistic canon is false on the face of it.

Another series of storms battering the West Coast gives way late in the day to a few precious minutes of sunshine. And more, much more, since as three-quarters of the sky continued to becloud and drizzle, the atmospheric prism produces a 180-degree rainbow as vivid and sharp as ever seen.

The depth of violet on the inner edge of the rainbow is especially riveting, leaving the mind and heart agape.

Truly, color is God, and the Brain is, or can be, wider than the sky.

Martin LeFevre

Link: Are Cyborgs In Our Future? ‘Homo Deus’ Author Thinks So