A conversation with a Buddhist teacher from India turned to the Buddha’s illumination. “The Buddha,” he said, “was attacked by Mara, but the Buddha came to see that the evil was within him.” Is that true, I asked?

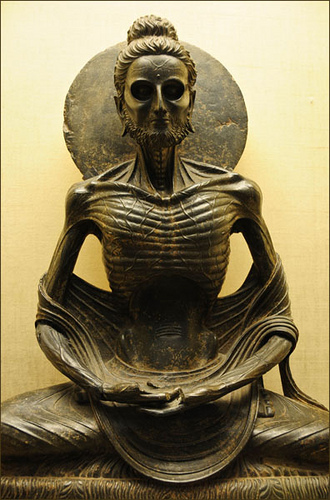

The story goes that as Siddhartha neared illumination, Mara came to him and challenged him, saying, the seat of enlightenment belongs to the greatest and only the greatest—who was he to claim it? Siddhartha did not react or respond, but merely reached out and touched the earth. Mara disappeared, Siddhartha was enlightened and the Buddha emerged.

The story goes that as Siddhartha neared illumination, Mara came to him and challenged him, saying, the seat of enlightenment belongs to the greatest and only the greatest—who was he to claim it? Siddhartha did not react or respond, but merely reached out and touched the earth. Mara disappeared, Siddhartha was enlightened and the Buddha emerged.

Recalling this story I asked the Buddhist teacher, “Do you mean to say that evil is only within the individual?” He was unsure for a moment, but instead of enquiring, he cleverly avoided the question by saying, “there is no duality.”

The ‘problem of evil’ is the most difficult one of philosophy, and no philosopher, East or West, has cracked it. Illuminating the nature and operation of evil has become a matter of inward and outward survival however, and as Euripides said, “nothing has more strength than dire necessity.”

We must meet darkness within, to be sure, but is the source and locus of evil within the individual? An experience I had with unvarnished evil in Russia 24 years ago rudely taught me otherwise.

It came during a trip to the Soviet Union a year before it fell. I’d flown to Moscow in January on business, and for the first two weeks found the Russian people in the capital, and in what was still Leningrad, very warm and hospitable. Unlike now, Russians respected and revered Americans, believing we would help them make the transition to a market economy and democracy.

Diplomatic relations were warming as well. Citizens of the United States had only been allowed to stay with our Cold War enemies in their homes some months previous to my visit. Few of the many Russians I met had had any direct contact with Americans before.

My Russian partner and host had been touted as a leading businessman under Gorbachev’s perestroika. After a few nights in the bosom of Andrei’s family, I felt very at home in their spacious Moscow apartment. But I began to feel that this fellow was a little too powerful after we went out a few nights to the best restaurants the average Russian never entered, and perhaps even knew existed. The places positively reeked of nomenklatura.

One evening, after a fortnight in Russia, Andrei announced that this was a special occasion, the 13th birthday of his eldest son. That’s the point of entry of a boy into manhood in the machismo Russian culture. I was the guest of honor.

We had an excellent dinner and enjoyable evening, which included a couple of drinks. Since a drink in Russia is nearly half a glass of vodka, following a ritual toast. Russians claim that the long toasts—little speeches really—keep them from becoming too inebriated. But I was buzzed.

On the way back I sat in the front with the driver, while Andrei, his wife Vera, and their two boys sat in the backseat of the roomy car. Vera, who had very little English, incongruously said something about evil.

Off the top of my head (a big mistake in responding to that subject), I said, “Evil can’t touch you if you remain with your fear.”

Until that point, I hadn’t felt a single moment of fear or homesickness in the strange land of Russia. But my feelings of warmth and fellowship were shattered the next moment.

I heard a metallic voice, which came through Andrei and seemed to emanate from well behind the car. In a tone of pure malevolence, it simply said, “Is that so?”

I’d known strong fear, even terror before, but the depth of the instantaneous, inexplicable terror I felt was far greater than anything I’d ever experienced, or knew existed. Suddenly the plush red curtains that had encircled me were ripped open. Before my eyes flashed scenes of incalculable suffering and death–scenes of gulags, mass torture and executions.

I felt like I’d been instantly transported to hell, and was on the backside of the moon, and was sure that I would never get home. The grimy snow that lined Moscow’s grim streets mocked my insular childhood on peninsular Michigan. Even the Stalinesque architecture, which  appeared just ugly and remote to me before, seemed to speak of evil.

appeared just ugly and remote to me before, seemed to speak of evil.

Without thinking it first, without thinking it at all, I held fast to the raging fear, and rode it like a rollercoaster for the next half hour, unable to speak. It abated, and I was forever changed.

Shortly after I returned to the West Coast, a philosopher friend asked what would have happened if I hadn’t done what I said. One of two things, I replied. Either I would have been shattered into a million pieces, or evil would have taken possession of me completely.

It’s no longer possible to avoid collective darkness and evil. The accretion of darkness in consciousness (which is consciousness as we usually know it) is destroying all space, inwardly and outwardly.

We all have our own share of darkness, inherited from the generations before us and accumulated in our own lives. Westerners blithely call it our personal “baggage,” ignoring the deeper lineage, while Buddhists call it karma, accentuating the non-personal content.

The content of that dark matter, comprised of all the unresolved hurts and hatreds, fear and loneliness within us, has built up generation after generation. And the totality of it in human consciousness, which we all share and to which we are all connected, is the collective darkness of humankind. Some element of that darkness has intentionality, just as some element within us has intentionality. That is the source and meaning of evil.

Except in the movies for entertainment purposes, darkness and evil are denied and avoided. But in observing, questioning, and remaining with the darkness within, one is constantly learning. And that turns the tables on evil.

When even a small minority of people live that way, evil will no longer rule the world.

Martin LeFevre