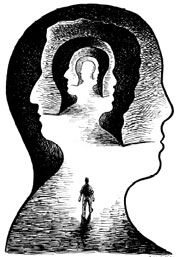

Descartes was wrong. He should have said: I think, and therefore I am divided. Then perhaps the world would not be so divided between East and West, North and South, Christianity and Islam.

Division, conflict, and war emanate from within people, not from economic or political structures. As much as economic and social structures contribute to the inequity and injustice of this world, they are not the source of these things. The world is the outward expression of the minds and hearts of every living person in it.

Division, conflict, and war emanate from within people, not from economic or political structures. As much as economic and social structures contribute to the inequity and injustice of this world, they are not the source of these things. The world is the outward expression of the minds and hearts of every living person in it.

This is obvious, and yet the inner origin of human division and discord is rarely seen and discussed. With the exception of poetry, which is a universal language of the human heart, we have no language for the inner landscape.

When one travels with sensitivity, or lives in a very different culture than the culture one grew up in, one emotionally realizes that people truly are the same psychologically. And yet the differences between people are still put first. Why?

The answer seems to be a vicious circle. Inwardly, we are divided, and that makes differences appear to be primary. Though differences are the spice of life, they become a source of division and conflict when one doesn’t emotionally perceive that people are essentially the same.

But what ends the habit of divisiveness? The root of division is the duality between ‘me’ and ‘my thoughts.’ In actuality, there is no separation between my thoughts and me—they are the same thing.

It takes intense yet passive observation to dissolve the separate observer and illusion of a permanent ‘me.’ The key to the brain doing so is not to interfere with what one is thinking and feeling, but just watch one’s associations and emotions as they arise, without judgment, evaluation, or labeling. Attention then grows, and it alone, without effort, will, or direction, quiets the mind and cleans the heart.

Without duality (and therefore division) it can be helpful to view the movement of thought and emotion in the present in terms of primary and secondary reactions.

Most of what passes for meditation is some form of concentration, but meditation has nothing to do with concentration. Also, the senses are often seen, even in the East, as an impediment, rather than what they actually are—the gateway to meditative states.

To meditate, one first allows the senses to be in the present. Sit outside if you can so you can feel the breeze on your skin, smell the fresh-cut grass, see the clouds scud across the sky, hear the hawk’s cry in the distance. Sound is the best teacher, because listening to sounds as they occur attunes one to the present and begins to opens space between thoughts in the mind.

Can one listen to one’s thoughts in the same way one listens to sounds? If so, a very interesting thing happens. The observer/self, with all its judgments and efforts, yields to what is, and falls away. Then thought and emotion unfold like a flower. They tell their story, and having been seen and heard, fall silent.

So the primary level of reaction is the mind’s reactions to stimuli—the spontaneous memories, associations and imaginings that jump all over the place are often referred to as ‘the monkey mind.’ Trying to control the chattering mind is the first mistake of all methods of  meditation. Control is suppression, exclusion and denial, whereas meditation is freedom, openness and truth. Methods and techniques, which are devices of thought, cannot do anything but hypnotize thought into silence.

meditation. Control is suppression, exclusion and denial, whereas meditation is freedom, openness and truth. Methods and techniques, which are devices of thought, cannot do anything but hypnotize thought into silence.

So the second level of reaction—the observer/self with all its judgments, ideas, evaluations and efforts—is the first mechanism to observe. One has to experiment and play with meditation, not try to reach any kind of goal or idea. They are the first things to let go.

When the ‘I’ makes efforts to reach an inner goal, the essential quality of non-interference in observation is denied. Intentional actions involve effort, but goals and effort have no place in meditation.

We have to make efforts in daily life obviously—to learn a subject, perform an athletic event, etc.–but they don’t require upholding a psychologically separate self, which is the very root of division. Obviously, it takes goals, planning, and effort to farm the land or build a house. But goals and effort are antithetical to inner growth.

New Age or old school techniques of meditation still require intentionality—that is, effort and will. And so they perpetuate division and conflict. True meditation dissolves the duality between the thought and the thinker, and so dissolves at its source the divisiveness and fragmentation that are destroying humanity.

To awaken observation in which there is no observer, just the action of observing, is a difficult art, but I’m sure anyone can do it if they question and experiment within themselves.

Reality is what our minds generate, motivated and elaborated by the observer; actuality is what we see and are part of when the observer ceases its infinite regression and thought falls completely silent. Descartes must be spinning in his grave.

Martin LeFevre