After spreading plastic and pads to ward off the dampness, a flock of robins greet me as I take my seat amidst the wet leaves. They land close by, and one swoops down and swerves within inches of my head. It seems more like play than aggression.

Stillness and mystery pervade the familiar streamside meditation place after the first rainstorm of the season. Despite or because of the overcast day, subtle light and color invoke immense, sublime beauty.

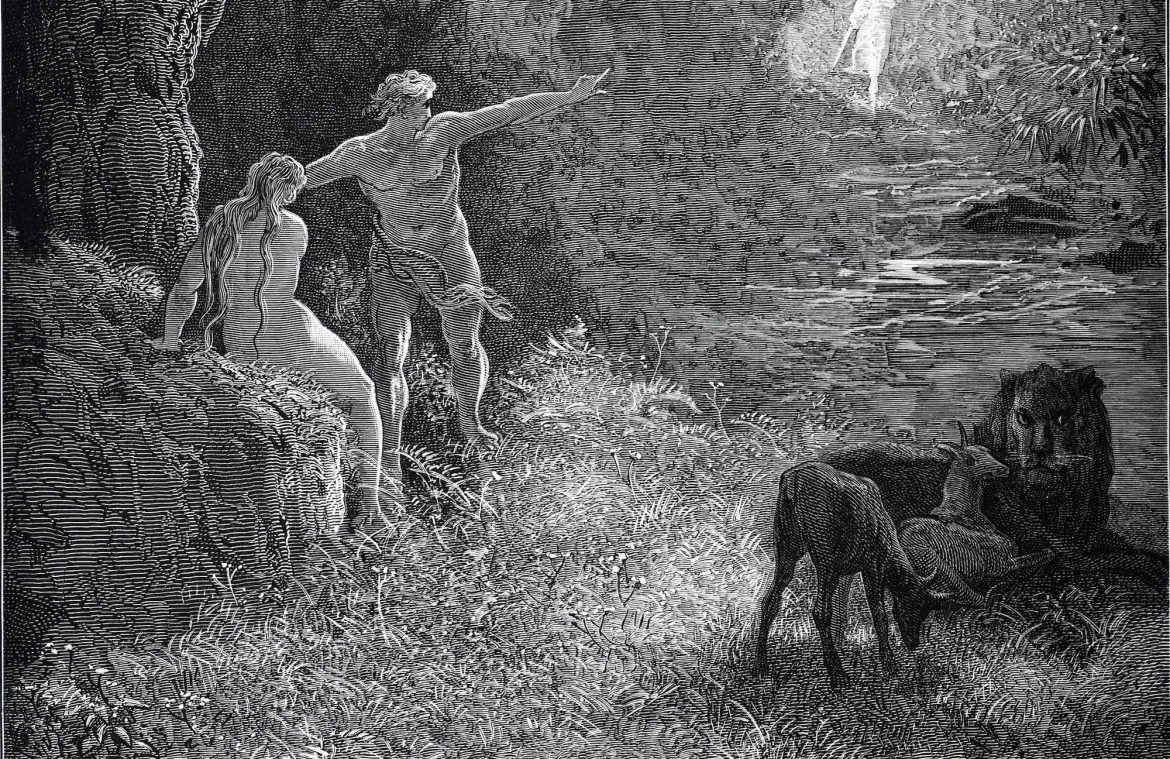

Soon every thought is incinerated in the flame of attention effortlessly gathered by passive observation. Near the end of the meditation, the sun pokes through the now-bare trees. Death, one realizes, is not the end, but the ground of being.

An unknown black and white bird with a huge crest lands on a branch in front of me, remains for only a second or two, and flies off downstream.

What is consciousness? Is it only that which takes place between our skulls, and is confined to humans? Or was the universe aware before it evolved conscious beings aware of the universe?

I understand consciousness in a twofold way: the clamorous, disordered consciousness that we know; and intrinsically ordered consciousness that that emerges when the movement we know is silent, negated in undivided and undirected attention.

The consciousness we know is comprised of words, images, memories, experience and knowledge. Whereas the consciousness we don’t know can never be part of the known, since it is always of the present, perpetually beginning.

What’s remarkable and paradoxical is that the evolution of the consciousness we know, based on symbolic thought, gave humans the capacity to commune with the consciousness of the universe, but it also prevents the human being from sharing in the awareness of the universe.

In deeper states of meditation, when the mind-as-thought is completely still and effortless, undirected attention to the outer and inner movement obliterates the distinction between the inner and outer, and one enters, without fear, the house of death. Without a trace of morbidity, death becomes an actuality, present in every breath, as it truly is.

The actuality of death is only fearlessly seen and felt when psychological time ends. Clearly, the separation of life from death was the first duality of thought. Apparently as soon as humans became conscious of our death and began to think in terms of time, we feared it, as the end of ourselves.

However the self is but a construct of thought emotionally experienced as separate and permanent. It’s actually just a bundle of images, memories and conditioning, infused with emotions and egoic attachment.

The self is not character, which to some degree we’re born with, or the soul, as the essence of ourselves in some indefinable way. But we cling to the self as if it were life itself.

In short, the self is a thing of thought, and human beings aren’t things, however much we may download our petty selves into the thought machines we’ve made in our own image.

The continuity of thought that we think of as ‘me’ certainly ends when the body expiries. So what is death with the ending of the self, at the end of our lives or while fully alive?

When the division between life and death ends in attention that quiets the entire movement of thought, one enters the house of death without fear. One doesn’t physically die, but death is present, as it actually is inside and outside the skin every moment.

Death, like love, is not personal. To ask, “What is death to you?” is not merely to ask the wrong question; it is to preclude asking the right one.

The death of a loved one is a crucible of grief and sorrow. But inwardly, can we live with death every day, so that when we physically expire, we’ve made a friend of death, and perhaps even transcended it?

Before the cycles of birth and death, including the birth and death of the universe itself, there was death, the ground of all matter, energy, life and being.

Touching that ground every day by allowing space for the silence of being, what is death? It is synonymous with awareness, creation and love.

Martin LeFevre